Russia’s faltering early phase of the invasion of Ukraine has put the Kremlin in a difficult position: it faced a choice between accepting the outcomes and attempting to backtrack, or continuing the fight despite mounting international sanctions, economic strain, demographic pressures, and other risks. The Kremlin chose to press ahead with mobilization and continue the war despite the costs, believing it could turn the battlefield in its favor. As Ukraine received increasingly sophisticated Western weaponry, from Javelin anti-tank missiles to modern MLRS and artillery systems in growing numbers, Moscow sought new partners to support its military efforts.

North Korea - a heavily sanctioned, cash-strapped state with a shared border and large stockpiles of compatible 152-millimeter artillery ammunition, emerged as a natural partner for Moscow. As North Korea increased shell deliveries to Russia, both countries started to face constraints: such as weak infrastructure which limited the efficiency of military shipments, and, more critically, remained inadequate for expanding economic cooperation.

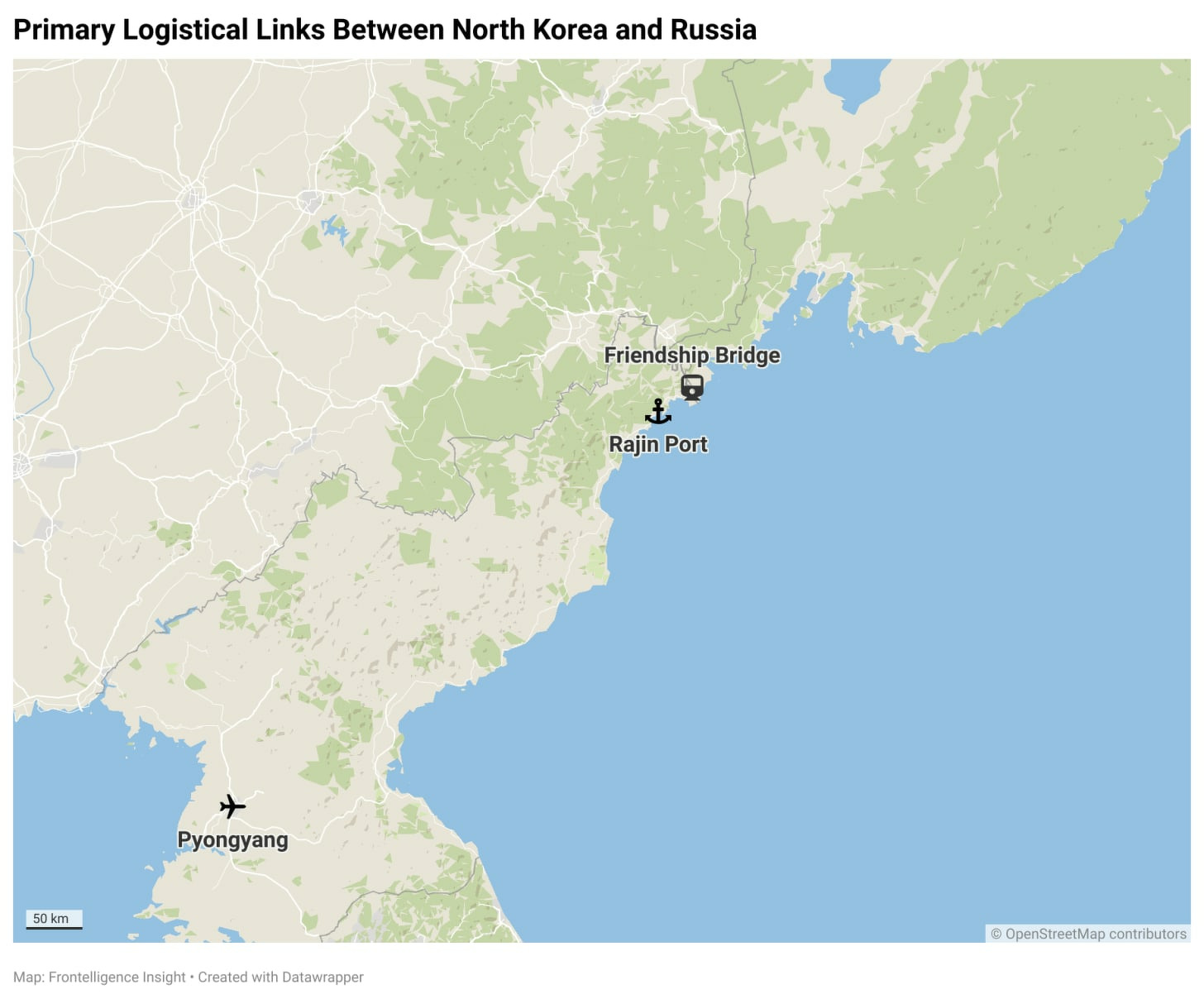

At present, Russia has no direct road connections with North Korea. The only existing land link is the Korea–Russia Friendship Railroad Bridge, opened in the late 1950s, which remains the sole fixed crossing between the two countries. Beyond that, bilateral transport relies on limited air connections, via Pyongyang International Airport, and maritime routes such as the North Korean port of Rajin. The port has gained renewed importance in recent years, serving as a logistics hub for shipments of artillery, mortars, and other ammunition supplied to Russia.

On June 19, 2024, the Kremlin announced an agreement with North Korea to build a road bridge across the Tumen River, a project long entertained since Soviet times but never brought to fruition, in part due to Chinese objections. Our team at Frontelligence Insight has analyzed project documentation, satellite imagery, and related materials to assess the potential impacts and strategic significance of the new bridge. This report presents the key findings and essential figures derived from our analysis.

Table of Contents:

Intro

I. Khasan–Tumangang Bridge Construction

II. Capacity and Volume

III. Summary and Broader Implications

Sources and references

I. Khasan–Tumangang Bridge Construction

The road bridge construction over the Tumen River is being managed by the construction firm TunnelYuzhStroy and carries an estimated price tag of nearly 9 billion rubles (roughly $110 million) funded through Russia’s federal budget.

The entire new bridge crossing, including new access roads, spans 4.7 kilometers, with the bridge itself expected to measure about one kilometer in length. According to official figures, the Russian section extends 424 meters and the North Korean side 581 meters. Our own measurements, however, indicate the bridge’s current length is closer to 835 meters, though it could reach the claimed one kilometer once bridge ramps are completed.

Construction began in early 2025 with preparatory work, including the development of logistics routes and access roads to the site. By October 14, 2025, satellite imagery shows steady progress on the new road bridge over the Tumen River. On the North Korean side, crews have advanced well into the middle of the river, constructing earthen cofferdams to install support piles. On the Russian side, at least two cofferdams are also visible, though progress there appears to be somewhat slower.

Both Russia and North Korea are simultaneously constructing special zones to house border control and customs authorities, effectively serving as entry points to their respective countries. The large building complex on the North Korean side has multiple structures, suggesting a mix of functions, including administrative offices and possibly inspection or support facilities.

At the current pace, barring severe weather-related delays, the bridge and its supporting infrastructure are expected to be completed by mid-2026, indicating that the project remains on schedule.

II. Capacity and Volume

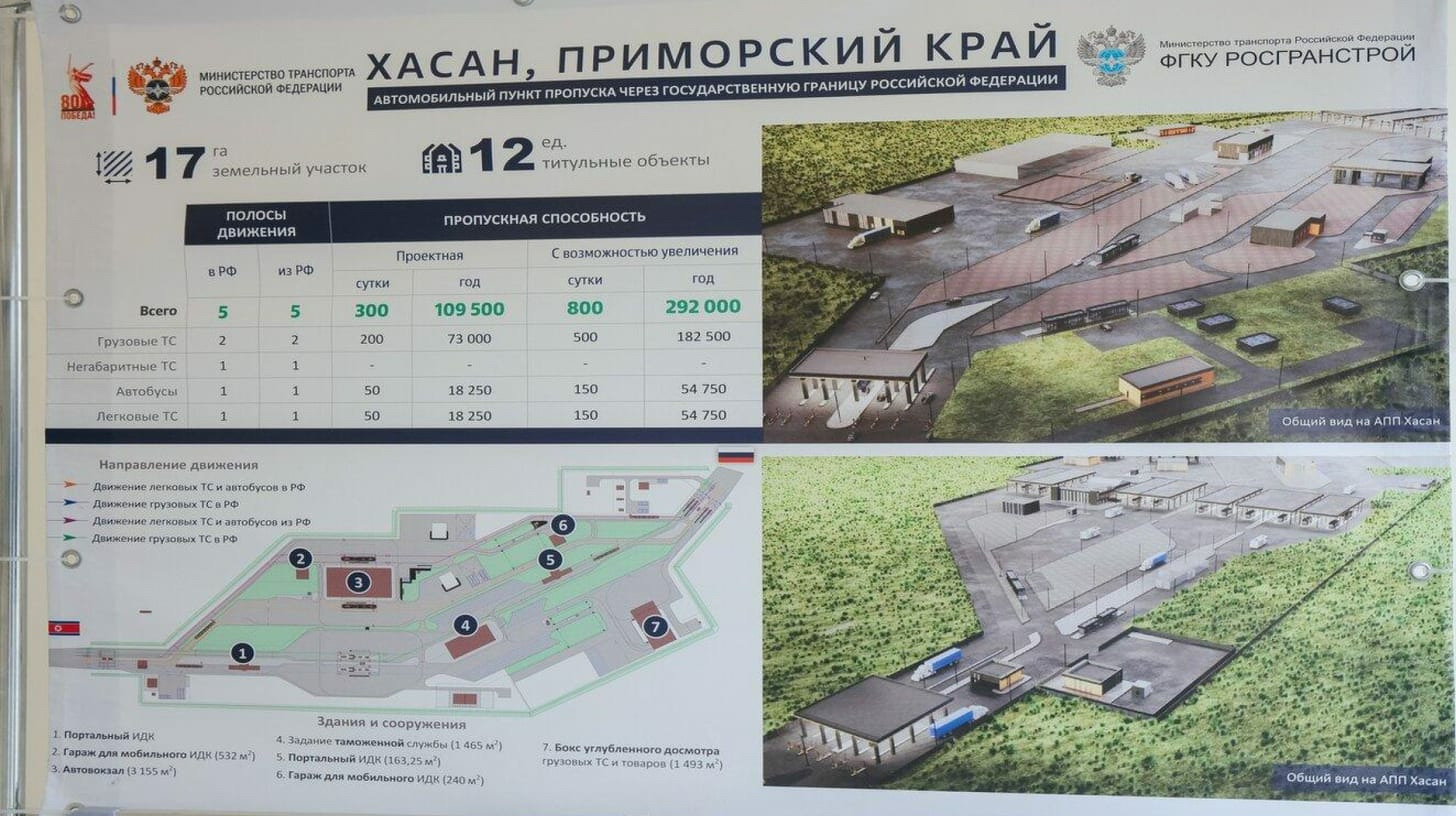

Khasan, a new automobile entry point on Russia’s side, will initially feature five lanes: two for cargo trucks, one for oversized vehicles, one for buses, and one for passenger cars. Its planned capacity is roughly 300 vehicles per day, or about 109,500 annually. With additional infrastructure and staffing, the crossing could eventually handle up to 800 vehicles daily, or nearly 292,000 a year.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Of the 300 vehicles the checkpoint can accommodate daily, cargo trucks are clearly prioritized, accounting for roughly 200 of the total. Annually, this could translate to a throughput of up to 73,000 trucks. Passenger traffic is expected to reach as many as 2,850 people per day

For context, we compared the projected capacity to another international road crossing, Zabaikalsk, which connects China and Russia. According to public statements, as of 2024, the checkpoint handled roughly 440 vehicles per day. While smaller, Khasan’s capacity remains notable given North Korea’s much smaller size and trade volumes

III. Summary and Broader Implications

Although attention often focuses on military cooperation between Russia and North Korea, their relationship extends well beyond arms sales, technology transfers, and direct combat support. Pyongyang seeks to strengthen bilateral ties to address its domestic socio-economic issues and to maintain leverage in its often fraught relationship with Beijing - a strategy it has pursued for decades. In this context, the regime’s top priority is survival, which also requires a degree of economic stability, including access to food, energy, and other essential resources that Russia can provide. Additionally, both countries, heavily sanctioned by the international community, assist each other in mitigating the impact of restrictions by finding alternative routes, bypassing controls, and improving sanctions resilience.

This dynamic is evident not only in joint initiatives, such as the bridge construction, but also in recent developments, including Russia’s agreement to deploy large numbers of North Korean engineers and workers to the Kursk and Vladivostok regions.

Constructing a road bridge would significantly improve logistics by overcoming the constraints created by the differing rail gauges of Russia and North Korea. Russia and North Korea use different rail gauges, requiring trains to operate on specialized dual-gauge tracks, which decreases overall efficiency. A functioning road crossing could lower per-unit transport costs, enabling Russian exporters to ship goods directly to the Rason special zone by truck, rather than relying on rail or detouring through alternative routes such as China. We expect to see increased trade in gasoline, grain, flour, other food products, chemicals, machinery and spare parts, construction materials, and timber.

That said, North Korea’s trade with Russia is unlikely to see a sharp increase in the near term, whether measured against either country’s GDP or their respective shares in overall exports, given the limited range of goods of mutual interest, the country’s modest purchasing power, and Korea’s relatively small population. Nor is Russia expected to come close to replacing China as Pyongyang’s principal trading partner. While the new bridge and related initiatives are likely to strengthen economic ties, it would be premature to describe the bridge construction as transformative - or as something that could overnight shift the geopolitical balance, either regionally or on the Korean Peninsula.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Sources and references

Supplement 6154. Kremlin. http://kremlin.ru/supplement/6154

Mishustin, M. (2025, February 1). Распоряжение №157-р. Official Internet Portal of Legal Information. http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/document/0001202502010001

Всеостройке (2025, September 21)Строительство автомобильного моста между Россией и КНДР: детали и перспективы. https://xn--b1agapfwapgcl.xn--p1ai/stroitelstvo-avtomobilnogo-mosta-mezhdu-rossiej-i-kndr-detali-i-perspektivy

Borovskaya, E. (2024, April 19). МАПП «Забайкальск» ждет глобальная реконструкция. ZAB.RU. https://zab.ru/news/173077

Jeong, T. (2025, July 7). Russia turns to N. Korean workers amid Western sanctions. Daily NK. https://www.dailynk.com/english/russia-turns-to-north-korean-workers-amid-western-sanctions

ASIAPRESS. 2025.09. 北朝鮮 超望遠動画