-

Serbian police crack down on protestors at mass anti-government rally in Belgrade

Police aggressively dispersed protestors at an anti-government rally in Belgrade, whereover 100,000 demonstrators gathered on June 28 to demand snap elections.

The rally marks the latest mass action in a protest movement that started last fall, with activists calling for an end to corruption and the 12-year rule of Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic.

Crowds in Belgrade on June 28 chanted “We want elections!” — a key demand of the movement that Vucic has consistently refused. His term ends in 2027, which is also the date of the next scheduled parliamentary elections.

Police officers in riot gear used tear gas, pepper spray, and stun grenades to forcibly dispersed crowds, according to multiple media outlets. Dozens of protestors were detained, though the police did not provide an exat number.

Serbian Interior Minister Ivica Dacic claimed that demonstrators attacked the police.

Protestors reportedly threw eggs, plastic bottles, and other objects at riot officers blocking the crowd from entering a city park where Vucic supporters were staging a counterprotest. Vucic reportedly bused in groups of his own supporters from around the country ahead of the rally.

As protests engulf Serbia, President Vucic looks for support East and WestEditor’s Note: Following a number of attacks against peaceful protestors in Serbia, the Kyiv Independent agreed to not publish the last names of people who gave comments for this story. BELGRADE, Serbia — Thousands of protestors walked 300 kilometers on March 1 from Belgrade to the southern city of Nis toThe Kyiv IndependentCamilla Bell-Davies

Vucic, a right-wing populist leader with authoritarian tendencies and warm ties with Russia, has repeatedly accused foreign states of inciting the protests in order to topple his government. He is provided no evidence to support these claims.

The current wave of protests in Serbia began in November, when a train station roof in the town of Novi Sad collapsed, killing 15. The disaster was blamed on government corruption.

While Vucic has alleged that Western powers are trying to trigger a “Ukrainian-style revolution in Serbia,” the Serbian protests are not markedly pro-Ukrainian or pro-Russian. Unlike mass demonstrations in Slovakia, where activists explicitly condemned the government’s Kremlin-friendly agenda, the Serbian movement is focused on Vucic’s corrupt leadership.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Serbia has attempted to navigate a delicate diplomatic path between Moscow and the West. It has positioned itself as neutral in the Russia-Ukraine war and balanced its status as an EU candidate with its longstanding ties to Russia.

Vucic made his first official visit to Ukraine on June 11.

Ukraine’s new top prosecutor known for high-profile cases, seen as Zelensky loyalistLoyalty to the incumbent administration has been the key requirement for prosecutor generals in Ukraine. Ruslan Kravchenko, who was appointed as prosecutor general on June 21, appears to be no exception. Previously he had been appointed as a military governor by President Volodymyr Zelensky and is seen as a presidential loyalist. Kravchenko became Ukraine’s top prosecutor after a lengthy hiatus during which the position of prosecutor general remained vacant. His predecessor, Andriy Kostin, r The Kyiv IndependentOleg Sukhov

The Kyiv IndependentOleg Sukhov

-

Ukraine war latest: Ukrainian drones reportedly strike 4 fighter jets in Russia

Key developments on June 27:

- Ukraine war latest: Ukrainian drones reportedly strike 4 fighter jets in Russia

- North Korea deployed 20% of Kim’s elite ‘personal reserve’ to fight against Ukraine in Russia, Umerov says

- Pro-Palestinian activists reportedly destroy military equipment intended for Ukraine

- Zelensky signs decree to synchronize Russia sanctions with EU, G7

- Russia’s short-range drone strikes cause over 3,000 civilian casualties in Ukraine, UN reports

Ukrainian drones struck four Su-34 fighter jets at the Marinovka airfield in Russia’s Volgograd Oblast overnight on June 27, Ukraine’s General Staff said.

The operation was carried out by the Special Forces and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) in cooperation with other military units, according to the General Staff.

Volgograd Oblast is located some 900 kilometers (560 miles) southeast of Moscow.

According to preliminary data, two Russian fighter jets were destroyed, and the other two were damaged. Russia uses such aircraft to bomb Ukraine, particularly to drop guided aerial bombs, the General Staff said.

The attack also caused a fire in the airfield’s technical and operational unit, a facility where combat aircraft are serviced and repaired, according to the General Staff.

The Kyiv Independent could not independently verify these claims.

As Russia intensifies aerial attacks on Ukraine and the civilian death toll climbs, Ukraine has stepped up its drone attacks on Russian territory. The recent surge in drone strikes aims to disrupt airport operations, overwhelm air defenses, and mount pressure against the Russian population.

Russia pulls its scientists out of Iranian nuclear plant, as Israeli strikes threaten decades of collaborationIsrael’s strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities have alarmed none more than Russia, the country that first brought nuclear power to Iran in defiance of Western objections. We’re “millimeters from catastrophe,” said Kremlin spokeswoman Maria Zakharova on June 18 in response to a bombing campaign that Israel launched against Iran on June 13. Decades of conflict with the West have united Iran and Russia, despite a cultural gulf between the two nations that dwarfs the Caspian Sea that physically di The Kyiv IndependentKollen Post

The Kyiv IndependentKollen Post

North Korea deployed 20% of Kim’s elite ‘personal reserve’ to fight against Ukraine in Russia, Umerov saysNorth Korea has already deployed around 11,000 elite troops to support Russia’s war against Ukraine, accounting for more than 20% of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s elite “personal reserve” force, Defense Minister Rustem Umerov said during a June 26 press briefing.

“These are soldiers specially selected based on physical, psychological, and other criteria,” Umerov said. “These units have already suffered significant losses."

Umerov said intelligence indicates North Korea had considered sending additional forces to fight with Russia. However, according to Umerov, the move would further deplete its strategic reserves and increase risks to regime stability. There have been four known rotations of North Korean units deployed against Ukraine, according to Umerov.

According to a June 15 report from the United Kingdom’s defense intelligence, North Korea has likely sustained more than 6,000 casualties in Russia since the deployment of troops to Kursk Oblast in fall 2024.

U.K. intelligence attributed the high casualty rate to large, highly attritional dismounted assaults.

Russia's growing military partnership with North Korea has raised concerns in Kyiv and among its allies. The two countries signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement in 2024. The treaty commits both countries to provide assistance if either is attacked.

Kim previously described the pact as having a "peaceful and defensive nature," framing it as a formal security guarantee between the longtime partners.

In practice, Umerov said, North Korea is bearing the military burden, while Russia has not upheld its reciprocal obligations, raising concerns within the North Korean regime.

"Russia's use of elite North Korean troops demonstrates not only a growing reliance on totalitarian regimes but also serious problems with its mobilization reserve," Umerov said. "Together with our partners, we are monitoring these threats and will respond accordingly."

Umerov added that Ukraine, working in coordination with its Western partners, is closely tracking the movement and deployment of North Korean units deployed to fight against Ukraine. He said Russia's dependence on foreign forces may signal critical shortages in its own recruitment and mobilization efforts.

According to South Korea's National Intelligence Service, North Korea is likely to send more troops to Russia over the summer. Pyongyang may also send up to 25,000 laborers to Russia to support drone production, according to the report.

The additional troop deployment would come on top of what Seoul estimates is already substantial support from North Korea, which includes the shipment of over 10 million artillery shells and ballistic missiles in exchange for economic and technical assistance from Moscow.

Tired of military aid delays, Ukraine has designed its own ballistic missile — and it’s already in mass-productionUkraine announced on June 13 that its short-range Sapsan ballistic missile would go into mass production, a major development in Kyiv’s ongoing efforts to domestically produce the weapons it needs to fight Russia’s full-scale invasion. As Ukraine faces growing challenges in securing weapons from Western partners, and Russia continues launchingThe Kyiv IndependentYuliia Taradiuk

Pro-Palestinian activists reportedly destroy military equipment intended for UkraineAround 150 pro-Palestinian activists have broken into a storage facility and damaged military equipment intended for Ukraine, the Belgian news outlet 7sur7 reported on June 26.

The facility belongs to OIP Land Systems, a company that produces military equipment for Ukraine. The activists reportedly thought the equipment would be supplied to Israel.

The activists, who were wearing white overalls and masks, took part in the Stop Arming Israel campaign. The protests seek to pressure Belgian authorities to maintain the military embargo against Israel and impose sanctions on it.

The protesters, armed with hammers and grinders, first entered the company's offices, where they smashed computers, and then broke into the hangars, where they severely damaged some vehicles, Freddy Versluys, CEO of OIP Land Systems, said.

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion, the company has supplied the Ukrainian army with about 260 armored vehicles. The damage caused by the activists' actions is estimated at $1.1 million, according to 7sur7.

"A further delivery has now been delayed by at least a month. That's all these Hamas sympathizers will have achieved with their action," Versluys said.

The company was reportedly targeted by pro-Palestinian protesters because Elbit Systems, an Israeli defense company, owns it.

Protesters believe that Elbit supplies 85% of the drones and most of the ground military equipment used by the Israel Defense Forces, 7sur7 reported.

Yet, the OIP Land Systems CEO claimed that his company has not produced defense systems for Israel for over 20 years.

OIP Land Systems has provided defense products to Ukraine on several occasions, including Leopard 1 tanks, which are manufactured at the Tournai plant.

Zelensky signs decree to synchronize Russia sanctions with EU, G7President Volodymyr Zelensky signed a decree on June 27 to coordinate sanctions against Russia with international partners, particularly the European Union and the Group of Seven (G7), the President's Office said on its website.

A day earlier, EU member states' leaders gave their political consent to extend the sanctions previously imposed on Russia for its war against Ukraine.

The EU Committee of Permanent Representatives (CORPER) also extended sectoral sanctions against Russia for another six months on June 26, European Pravda reported, citing a diplomatic source. The sanctions include restrictions against entire sectors or industries of the Russian economy or areas of operation of Russian businesses.

Meanwhile, the participants did not approve the new 18th package of sanctions, which targeted Russia's energy and banking sectors, due to Slovakia's veto.

Zelensky's June 27 decree implements a decision by Ukraine's National Security and Defense Council's (NSDC) to synchronize the sanctions against Russia with the EU and G7.

According to the document, sanctions approved by partner states must be submitted to the NSDC for consideration and approval no later than the 15th day after the partner state's decision comes into force.

The Cabinet of Ministers, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), and the National Bank of Ukraine must also ensure the implementation of sanctions approved by international partners in Ukraine.

After the 17th package of sanctions against Russia took effect on May 20, Ukraine's allies announced the following day that another round of restrictions was already in the works.

The push for tighter sanctions comes as Russia continues to reject ceasefire proposals and presses forward with military operations.

Russia's short-range drone strikes cause over 3,000 civilian casualties in Ukraine, UN reportsShort-range drone attacks have become one of the deadliest threats to civilians in Ukraine’s front-line regions, killing at least 395 people and injuring 2,635 between February 2022 and April 2025, according to a new bulletin by the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine.

The report, "Deadly Drones: Civilians at Risk from Short-Range Drones in Frontline Areas of Ukraine," highlights the growing use of first-person-view (FPV) drones by Russian forces and their devastating impact on the civilian population.

The bulletin documents attacks in which drone operators deliberately targeted civilians engaging in daily activities — driving private cars, riding bicycles, walking outdoors, or evacuating others in clearly marked ambulances.

"Although individually less destructive than artillery or missiles, the sheer scale and increasing frequency of short-range drone attacks have made them one of the deadliest weapons in Ukraine," said Danielle Bell, head of the mission.

"Over 3,000 civilian casualties — and the relentless frequency of these attacks — have not only caused immense human suffering but also instilled fear, severely disrupted daily life, and crippled access to essential services in several frontline communities."

The monitoring mission documented, verified, and analyzed 3,030 civilian casualties resulting from short-range drones between 24 February 2022 and 30 April 2025.

The researchers conducted site visits to very high-risk areas, including the southern city of Kherson, Zolochiv in Kharkiv Oblast, and other front-line locations. Investigators interviewed survivors and witnesses of drone attacks, medical personnel, and humanitarian workers to assess the full impact of these strikes on civilian life.

Ukraine's Kherson Oblast (Nizar al-Rifai/The Kyiv Independent) Casualties surged in late 2023 and early 2024, with numbers suddenly doubling in July 2024. April 2025 marked the deadliest month on record, with 42 civilians killed and 283 injured. Drone strikes continued into May and June.

On 23 June, a 65-year-old driver was killed in Kostiantynivka, Donetsk Oblast, when a drone struck a minibus. In Kharkiv region, a 58-year-old volunteer was killed on 22 May when a drone dropped a munition on a residential balcony. On 20 May, six civilians were injured when a drone hit a bus in Kherson Oblast.

The vast majority of casualties — 89% — occurred in territory controlled by the Ukrainian government. The UN says these attacks violate international humanitarian law, particularly the principles of distinction and precaution, and may in some cases constitute war crimes.

Note from the author:

Ukraine War Latest is put together by the Kyiv Independent news desk team, who keep you informed 24 hours a day, seven days a week. If you value our work and want to ensure we have the resources to continue, join the Kyiv Independent community.

-

Pro-Palestinian activists reportedly destroy military equipment intended for Ukraine

Around 150 pro-Palestinian activists have broken into a storage facility and damaged military equipment intended for Ukraine, the Belgian news outlet 7sur7 reported on June 26.

The facility belongs to OIP Land Systems, a company that produces military equipment for Ukraine. The activists reportedly thought the equipment would be supplied to Israel.

The activists, who were wearing white overalls and masks, took part in the Stop Arming Israel campaign. The protests seek to pressure Belgian authorities to maintain the military embargo against Israel and impose sanctions on it.

The protesters, armed with hammers and grinders, first entered the company’s offices, where they smashed computers, and then broke into the hangars, where they severely damaged some vehicles, Freddy Versluys, CEO of OIP Land Systems, said.

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion, the company has supplied the Ukrainian army with about 260 armored vehicles. The damage caused by the activists' actions is estimated at $1.1 million, according to 7sur7.

“A further delivery has now been delayed by at least a month. That’s all these Hamas sympathizers will have achieved with their action,” Versluys said.

The company was reportedly targeted by pro-Palestinian protesters because Elbit Systems, an Israeli defense company, owns it.

Protesters believe that Elbit supplies 85% of the drones and most of the ground military equipment used by the Israel Defense Forces, 7sur7 reported.

Yet, the OIP Land Systems CEO claimed that his company has not produced defense systems for Israel for over 20 years.

OIP Land Systems has provided defense products to Ukraine on several occasions, including Leopard 1 tanks, which are manufactured at the Tournai plant.

With no new US aid packages on the horizon, can Ukraine continue to fight Russia?The U.S. has not announced any military aid packages for Ukraine in almost five months, pushing Kyiv to seek new alternatives. But time is running out quickly as Russian troops slowly advance on the eastern front line and gear up for a new summer offensive. “While Ukraine’s dependence onThe Kyiv IndependentKateryna Hodunova

-

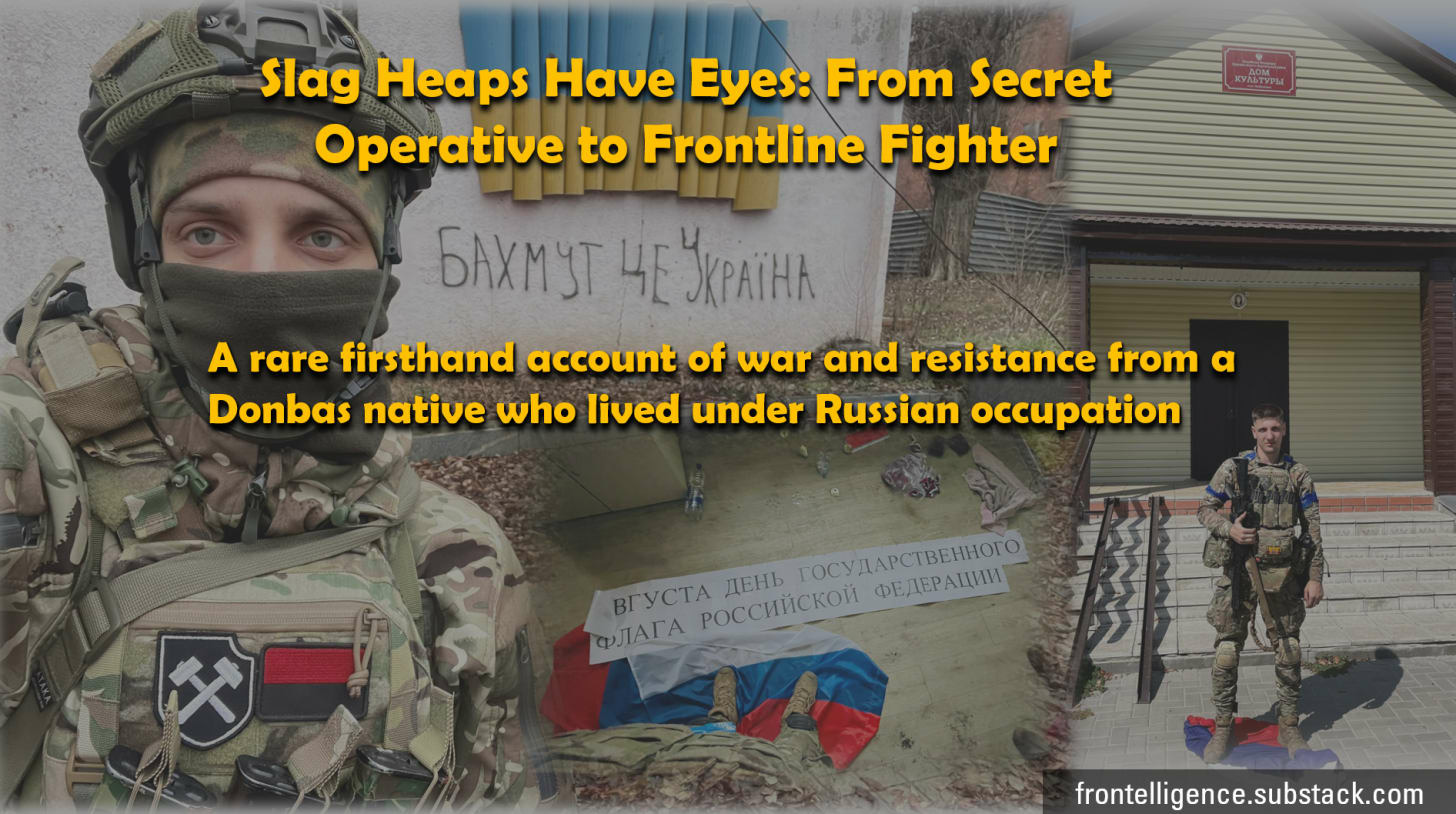

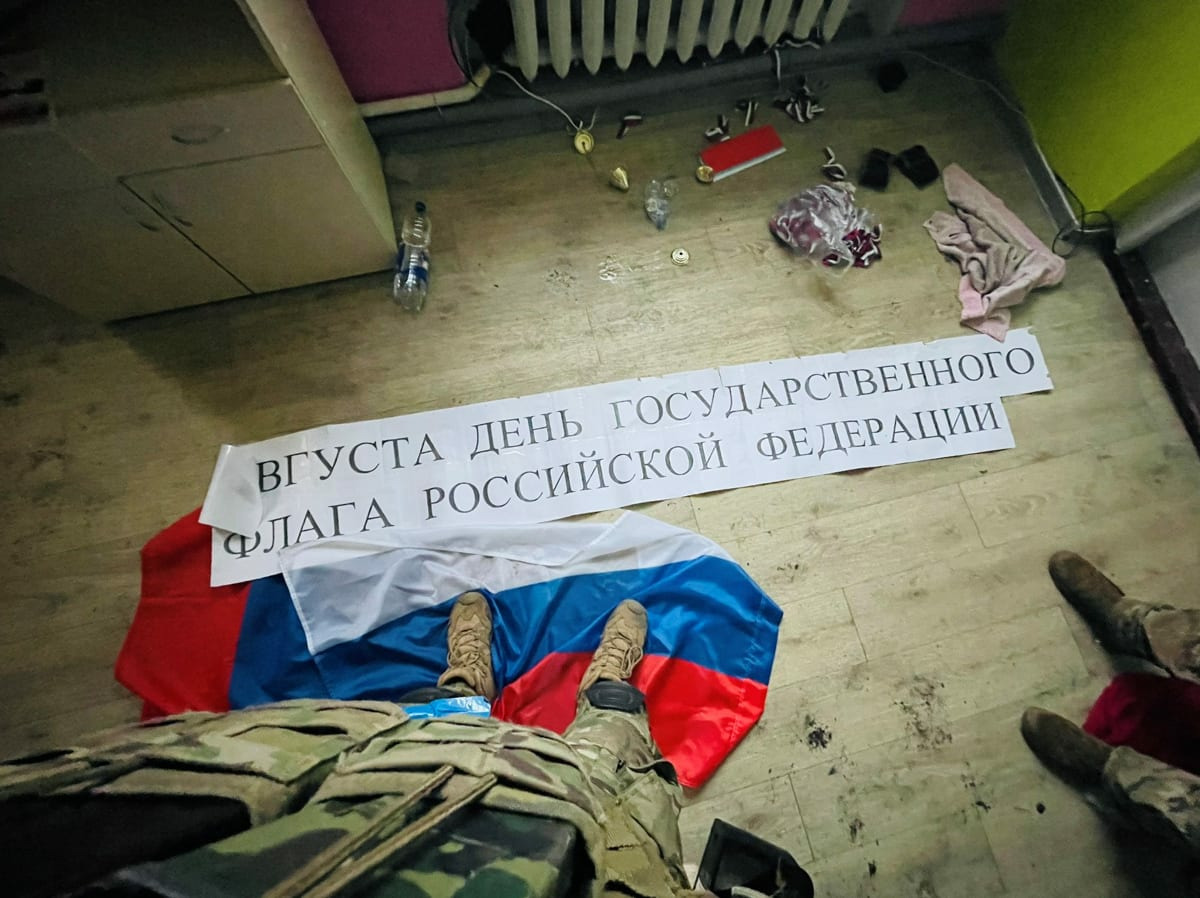

Slag Heaps Have Eyes: From Secret Operative to Frontline Fighter

A native of Donbas and veteran of Ukraine’s fiercest battles, Artem Karyakin, better known by his nom de guerre, Skhidnyi, offers his firsthand view from the front lines of the war. For years, he operated in secrecy as a spotter for Ukrainian intelligence deep inside occupied territory. When the full-scale invasion began, he joined the ranks of the Ukrainian forces and has since fought without pause - from the defense of Kyiv to the grinding battle for Bakhmut and the incursion in Kursk.

In this special interview, Artem Karyakin traces the origins of the Russian occupation in Donbas, weighs the prospects for reintegration of lost regions, and recounts what the battle for Kursk truly looked like on the ground. To continue our efforts to document this war and the experiences and opinions of participants at this historic moment, we are publishing the full interview

1. Frontelligence Insight (hereafter FI): You are originally from Donbas and witnessed the unfolding of Russian aggression in the region. How exactly did it happen, and what were you doing in 2014?

Artem “Skhidnyi” Karyakin (hereafter - A): It’s important to note that the Russians began preparing for the seizure of Donbas well before 2014. This was especially evident to us—the residents of the region. For example, in my hometown of Kadiivka (formerly Stakhanov) in Luhansk Oblast, a certain “Don Cossack” organization appeared in the early 2000s. It consisted of marginal figures dressed in red Cossack hats and carrying whips. It looked strange, as our city had always been known for its mining industry and had no historical connection to the Don Cossacks.

This organization attracted people with chauvinistic views, fanatically devoted to the idea of reviving the USSR and uniting the "Slavic peoples." For instance, in 2012, a march commemorating the Ukrainian Insurgent Army was held in our city, in which I also participated. The march was disrupted when we were attacked by the same Don Cossack group, along with paid activists from the “Party of Regions.” Even back then, these “Cossacks” were confiscating our Ukrainian flags. That moment was very telling.

By 2014, the same “Cossacks” in red hats were seizing government buildings in our city - only now they were armed and operating under Russian flags. Many of them weren’t even born in our city - they came from the Russian Federation, as did some of those who helped them seize power by force in the spring of 2014.

We — the pro-Ukrainian residents of the city — were organizing events in support of Ukrainian unity at that time. Our first event was a memorial rally honoring the “Heavenly Hundred” (Editor’s note: The "Heavenly Hundred" refers to those who were killed during the 2014 protests against the Yanukovych regime in Ukraine). That was in late February 2014. Later, we held car rallies for Ukrainian unity, events on the birthday of Taras Shevchenko, and actively distributed pro-Ukrainian leaflets and stickers around the city, and painted Ukrainian flags.

Pro-Ukrainian flyer titled "United Country" pinned to a public notice board, March 2014. Photo shared by Artem “Skhidnyi.” All our activities in the spring of 2014 were dangerous, as there were already armed Russians and local pro-Russian militants in the city.

The point of no return came in late spring 2014, when two young guys — still in school — put up a Ukrainian flag on a slag heap in the center of town. They were fired upon with a handgun for doing so. After that, many pro-Ukrainian residents began leaving the city, as it had become clear that they could simply be killed for their love of Ukraine.

2. FI: What happened to the pro-Ukrainian activists? Are there still people who maintain a pro-Ukrainian stance under occupation?A: I remained in my occupied city until the end of 2021, as did many others who loved Ukraine but, for obvious reasons, could not express it publicly. Today, the situation has worsened for those who support Ukraine in the Russian-occupied cities.

There are still many such people, but they are forced to live in fear, expecting to be arrested at any moment. Russian security services have dedicated significant resources to identifying and detaining pro-Ukrainian residents in the occupied territories. There are constant filtration procedures and ongoing inspections. Special attention is given to public sector workers and even to children. For example, in schools, there are mandatory checks of students’ mobile phones to look for subscriptions to Ukrainian media or messages expressing pro-Ukrainian views.

To love Ukraine under Russian occupation is already an act of courage.

Nevertheless, even today, a large number of true Ukrainians remain in the occupied territories: people who, risking their lives daily, help us in the fight against Russia by sharing intelligence, carrying out sabotage, and participating in other acts of resistance against the Russian army. This is true heroism and further proof that this land is rightfully Ukrainian.

3. FI: You continued to support Ukraine even when your city was already under occupation. What exactly did your activities involve?A: In July 2014, while already living under occupation, I created my first Twitter account. The goal was to shed light on the situation in the occupied territories from the perspective of a pro-Ukrainian resident who hadn’t left their home. At the time, neither people in Ukraine nor the rest of the world fully understood what was actually happening. Many believed that all the locals who had stayed supported Russia. I wanted to show the world that our city was occupied by Russia, and that there were still Ukrainians there who were not happy about it and were waiting for the Ukrainian army.

In addition to general updates, I also posted information about the locations of Russian troops in my city. These were public tweets, sometimes with maps marking where Russian military equipment was stationed. In the fall of 2014, I was contacted via direct message on Twitter by representatives of Ukrainian intelligence services as well as acquaintances from the Ukrainian army. They explained to me that it was better to share intelligence privately rather than posting it publicly on Twitter.

Since then, I began secretly passing on various types of information to the Ukrainian army and intelligence services - details about the movements, positions, and firing points of Russian forces in my city and surrounding occupied areas. Over the years, this also came to include information about factories and enterprises operating under Russian control, the socio-political climate under occupation, local sentiment, and data on collaborators - those who had joined the Russian side in combat or taken positions in the Russian-controlled security services.

4. FI: In 2021, you moved to Ukrainian-controlled territory, and the full-scale invasion began the following year. How did you join the Armed Forces, and what was your first battle?A: From the very first days of Russia’s full-scale invasion, I began looking for a unit where I could fight against Russia. The early days of the big war were chaotic—there was disorganization and confusion everywhere. I was living in Kyiv, and in one of the first days of March, I simply approached some guys with rifles and offered my help. That very same day, I was already standing night watch with Kalashnikov's hand-held machine gun in my hands.

It was one of the Territorial Defense Force units. We took up a defensive position on the outskirts of Kyiv, on the Bucha-Irpin side. In the summer of 2022, I joined the fighters of the 8th Regiment of the Special Operations Forces, where my friend was already serving and had invited me to join his group.

My first combat deployment was in August 2022 in Bakhmut, which at that point was already under assault by Russian forces, including Wagner PMC fighters. Shortly after Bakhmut, we took part in the liberation and clearing of the city of Lyman, in Donetsk Oblast. For me and many of my fellow soldiers, it was our first experience liberating our native land - a moment we will remember forever.

5. FI: You’ve taken part in important operations - both in Ukraine and on Russian territory, specifically in the Kursk region. Did you notice any significant differences between combat operations in Ukraine and in Kursk?

A: The Kursk operation was unique in every sense and differed from my past experiences in Ukraine in many ways. It was in the Kursk region that I first encountered the concept of maneuver warfare, and I can say that, personally, combat along a clear front line is easier for me.

It was also in Kursk where we first faced FPV drones connected via fiber optics and a new Russian tactic—using specialized FPV drone teams to strike our logistics routes from as far as 10–15 km deep. This tactic is now widely used by Russian forces along nearly every front.

In this operation, we also faced the enemy’s best FPV crews, all concentrated in one relatively small sector. These teams had been withdrawn from other areas and redeployed to Kursk specifically.

Another major difference was that, for the first time, we were acting as a “foreign army” in populated areas. Each soldier had their own reaction to that: for some, it felt like justified revenge; others felt a strong pull back toward our own land and a kind of inner resistance to advancing on foreign soil.

I count myself among the former. For me, it was an act of rightful retribution and a way to shift the war onto the aggressor’s territory. Yet I constantly reminded myself that I didn’t want to behave like the Russians did in my hometown. On Russian territory, I acted very differently than they had in ours. To every civilian I encountered in the Kursk region, I explained why we were there, how it all began, and that we simply want to liberate our own cities - not seize theirs.

The Kursk operation was very well planned and executed at the outset, but unfortunately was marred by a series of key mistakes and issues at various levels. These mistakes must be carefully analyzed so they are never repeated. I sincerely hope this experience proves useful in the future—it was unique in many respects.

Regardless, everyone who took part in that operation became part of history. We shattered the myth of the invincibility of a nuclear power and the so-called greatness of the Russian army. We drew significant enemy forces away, slowing their advance on our territory. And we were also the ones who fought against the armies of two different totalitarian states. The experience of facing North Korean forces is also something that sets this apart from the war in Ukraine—even though their tactics in Kursk didn’t differ much from what Wagner used in Bakhmut.

6. FI: Assuming that Russia eventually loses control over Donbas - how do you envision the process of reintegrating these territories? How deeply has Russian propaganda taken root there over the years?A: The most important thing is to drive the Russians out of our land. And with Ukrainians, just like us, we’ll quickly find common ground.

The main issue with those who fell under the influence of Russian propaganda during the occupation is that they know very little about the rest of Ukraine. Many have never been to other regions and know nothing about them. Everything they do know about Ukraine comes from what they’ve seen on Russian TV channels.

Another problem is that Russia created conditions in which every second family in occupied Donbas has lost a relative in the war. This is a direct result of the forced mobilization of men from the occupied territories into the Russian army.

But you have to understand — Donbas, especially the part that’s been under occupation since 2014, is a region where people generally lack any strong civic engagement or passion. Their opinions and actions are shaped entirely by the environment they live in.

If Ukraine returns to these territories, people will quickly adapt to new rules and new flags flying over their homes. And soon, they will realize that life under Ukraine is freer and more breathable. Without the presence of Russian troops, these people would never have fought for the Russian flag. I know them — I lived among them for most of my life.

Even now, many of them no longer see Russia as something positive. After living under the Russian flag long enough, they’ve come to realize that there’s little good there, and that the sacrifices they were forced to make for that flag were not worth it.

7. FI: When the war ends, what do you see your life looking like? Do you have any dreams or plans for peacetime?

A: The most important thing is for the war to end with our victory. We must preserve Ukraine and bring back our land and our people. I’m turning 28 this year, and I’ve spent 11 of those years living through war — it’s hard to imagine myself without it now.

But of course, I have a personal dream as well: to start a family of my own. During the years of occupation, I lost my parents and my grandmother, and since then, the feeling of loneliness has never left me. My dream is a family… my children, who will never know what war is.

============================================================================

Artem “Skhidnyi” Karyakin, in an exclusive interview with Frontelligence Insight. You can follow him on the X platform for firsthand updates from the front.This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

-

Russia still hasn't declared war on Ukraine, and doing so could spell Putin's demise, experts say

Despite suffering over 1 million casualties, pounding Ukrainian cities nightly with missiles and drones, and committing countless war crimes, one startling fact about Russia’s full-scale invasion remains — Moscow has yet to officially declare war on Ukraine.

In February 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin described what he believed was going to be a swift victory and the capture of Kyiv within days as a “special military operation."

Nearly three-and-a-half years later, the Kremlin is stuck with the term, caught in a quandary of its own making — waging by what any measure is a war, while being unable to call it one for fear of a domestic backlash.

“Putin has protected himself in this war by separating the direct effects of the war from the majority of the Russian population.”

A formal declaration of war would have far-reaching implications for the country's industry and economy, as well as allowing the Kremlin to launch a full mobilization.

But partial mobilization announced in September 2022 led to the only widespread protests against the war inside Russia, making clear to Putin that announcing anything more would cause him serious political problems.

"Putin has protected himself in this war by separating the direct effects of the war from the majority of the Russian population," Karolina Hird, Russia deputy team lead at the Institute for the Study of War, told the Kyiv Independent.

"But as soon as that starts to spill over and actually be felt by more of the Russian domestic population, that's when he gets into more trouble."

According to reports, there has recently been unrest within the Kremlin after Ukraine's audacious Operation Spiderweb, with hardliners reportedly pressuring Putin to make a formal war declaration that would permit true retaliation and escalation, and give the Russian government sweeping authority to shift the country fully onto a wartime footing.

But experts who spoke to the Kyiv Independent say this is unlikely, arguing that for all intents and purposes, Russia's industry and economy are already on a wartime footing even if Kremlin officials deny this, and that Putin simply can't risk his hold on power by launching what would be a deeply unpopular mobilization.

Youths walk past a billboard promoting contract army service with an image of a serviceman and the slogan “Serving Russia is a real job” in Saint Petersburg, Russia, on Sept. 29, 2022. (Olga Maltseva / AFP via Getty Images)

Russian citizens drafted during the partial mobilization are seen being dispatched to combat coordination areas after a military call-up for the Russian invasion of Ukraine in Moscow, Russia, on Oct. 10, 2022. (Stringer / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images) What would a Russian declaration of war mean?The two major factors that would come into play are the Russian economy and the Russian people.

A full war footing would be a complete pivot of the economy and its workers towards defense and the production of weapons, and allow for a full mobilization to conscript the necessary manpower to use them.

The Kremlin is projected to allocate 6.3% of its GDP to defense this year — the highest level since the Cold War — yet still far below what would typically indicate a country fully mobilized for war.

By contrast, Ukraine spent 34% of its GDP on defense last year, while British military spending surpassed 50% of GDP during the Second World War.

These same figures were cited by Russian Ambassador to the U.K. Andrey Kelin in an interview with CNN last week as evidence that Russia was in fact still fighting a "special military operation," and not a war.

Experts are not convinced.

"The Russian economy is already on a war footing, and the 6.5% of GDP spent on defense for 2025 is likely an underestimation," Federico Borsari, a defense expert at the D.C.-based Center for European Policy Analysis, told the Kyiv Independent.

"Defense production in key capability segments such as drones, missiles, and armored vehicles is at full steam, with up to three worker shifts per day."

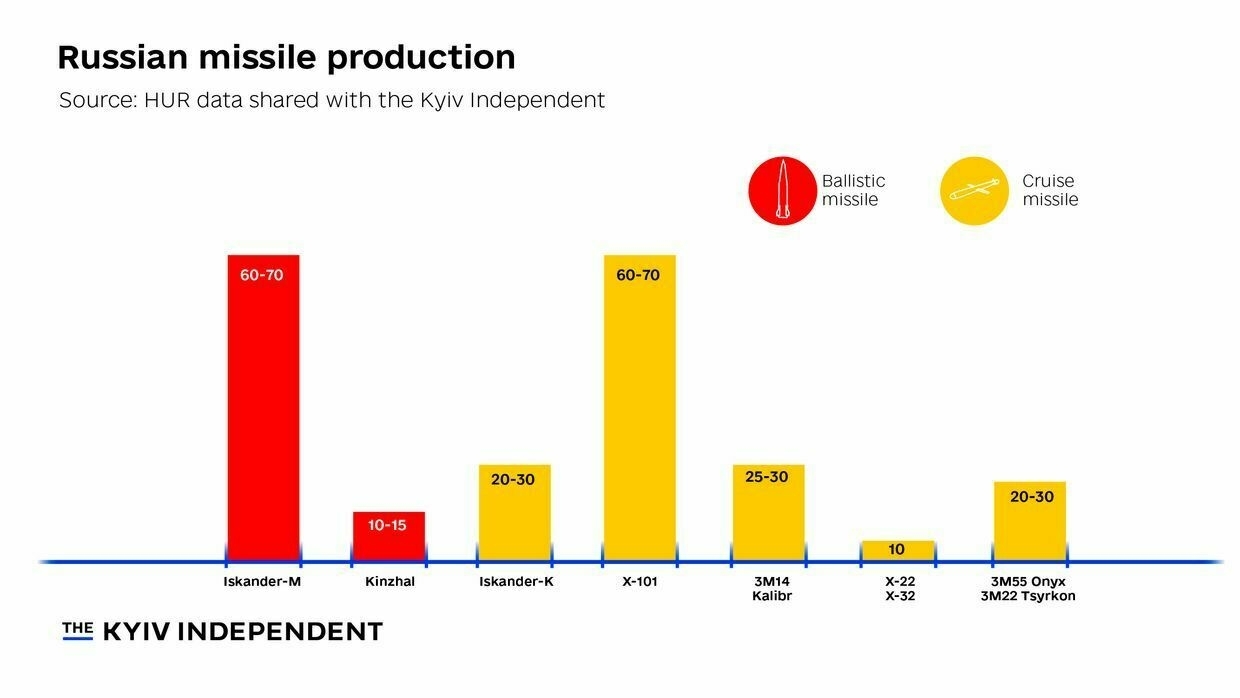

Russia has drastically upped weapons production in recent months as it drains its stockpiles.

According to data from Ukraine's military intelligence (HUR) shared with the Kyiv Independent earlier this month, production of ballistic missiles, for example, has increased by at least 66% over the past year.

Russian missile production per month. (The Kyiv Independent) Hird agrees with Borsari's analysis, saying the massive boost in defense manufacturing is a sign that, despite Russia's claims that it isn't at war, its depleted stockpiles are a pretty clear sign they are.

"It's not like Russia has a secret reserve of weapons in the background that it can somehow kind of unlock and unleash on Ukraine," she said.

"Russia is already fighting an all-out war in Ukraine, so there's actually not much more that can be done on their side."

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin visits Uralvagonzavod, the country’s main tank factory in the Urals, in Nizhny Tagil, Russia, on Feb. 15, 2024. (Ramil Sitdikov / Pool / AFP via Getty Images)

Destroyed Russian tanks lie in a field near the village of Bohorodychne in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine, on Feb. 13, 2024. (Maxym Marusenko / NurPhoto via Getty Images) The manpower issueThe one crucial area in which a declaration of all-out war against Ukraine could significantly boost Russia's ability to wage war is manpower.

Throughout the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Putin has steered clear of a full mobilization, conscious of the domestic backlash it would create.

Instead, the Kremlin has simply paid people to fight, offering huge sign-up bonuses to encourage people to volunteer, a method which, up to now has managed to replenish the huge losses the army has incurred, but which many experts think is unsustainable.

"In terms of manpower, Russia still has a sizeable population pool it can draw from, at least in the near term, especially in peripheral regions," Borsari said.

"However, this pool may not be sufficient to sustain the current pace of losses, with thousands of casualties each week, beyond the first half of 2026."

With no end to the war in sight, that looming deadline will likely pose a huge dilemma for Putin — how to find enough men to fight, without losing his hold on power?

"They are aware of the massive risks involved and Putin is rather risk-aversive," Ryhor Nizhnikau, a Russia expert at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs, told the Kyiv Independent.

"Full mobilization is expected to have a destabilizing effect on Putin’s regime, the already ailing Russian economy, and it will certainly unbalance the current public consensus on the war."

US President Donald Trump in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, DC, U.S., on June 18, 2025. (Ken Cedeno / UPI / Bloomberg via Getty Images) The geopolitical aspectDeclaring war on Ukraine would also have international ramifications for Putin, Shea said.

"He will no longer be able to pretend to (U.S. President Donald Trump and (U.S. Special Envoy Steve) Witkoff that he is interested primarily in a partial victory by taking only the Donetsk region and Crimea," he said.

"He also said in St Petersburg last week that Russia posed no threat to NATO and that NATO was rearming for nothing. But a formal Russian declaration of war will convey the entirely opposite message."

Putin insists the Russian economy is fine, but Kremlin officials say otherwiseIn a rare public sign that all is not well in Russia, two high-ranking Moscow officials last week issued separate warnings about the state of the country’s economy. Russian Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina and Economy Minister Maxim Reshetnikov both highlighted that amid the Kremlin’s full-scale war against Ukraine, the tools Moscow once relied on to maintain wartime growth are nearly exhausted. Almost immediately, Russian President Vladimir Putin on June 20 dismissed the concerns, clai The Kyiv IndependentTim Zadorozhnyy

The Kyiv IndependentTim Zadorozhnyy

-

Trump gets king’s treatment at NATO summit while Ukraine sits on the sidelines

THE HAGUE, Netherlands — As NATO leaders convened in The Hague for a two-day summit on June 24–25, allies and Kyiv braced for the first annual meeting since U.S. President Donald Trump’s return to office.

With the Israel-Iranian conflict dominating the news and the summit agenda focused on the new 5% defense spending target, Ukraine no longer took center stage.

This was chiefly because of one man: Trump has shown little appetite for ramping up military assistance for Ukraine, and there are growing fears he might disengage from the war altogether.

He has also ruffled the feathers of his NATO allies by publicly doubting the U.S. commitment to Article 5.

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte set out to demonstrate that transatlantic unity remains strong — even if that meant appeasing Trump with flattery and deprioritizing potentially divisive topics like Ukraine.

This shift was underscored by the summit’s final statement, which offered little more than stale words of comfort to the war-torn country, even as Russia launched new large-scale attacks against its cities.

President Volodymyr Zelensky did not leave the summit empty-handed, however. He got his much-desired meeting with Trump, which seemed to have gone smoothly.

Rutte also sought to reassure Kyiv that support for Ukraine holds, stressing that allies have committed some 35 billion euros ($40 billion) in aid to Ukraine this year so far, about 10 billion euros more than in the first half of last year.

But it hasn’t dispelled the sense that an era is ending — one in which Ukraine’s struggle against Russia held an unquestioned place at the center of NATO’s agenda.

Ukraine’s small victoriesThe NATO summit wasn’t a complete failure for Ukraine. In fact, the most pessimistic rumors swirling around in the lead-up to the event did not come true.

Zelensky did, after all, receive an invitation to the summit, dispelling speculation that Ukraine would be left out due to opposition from the U.S. He also managed to have a face-to-face meeting with Trump for the first time since their brief talk in the Vatican in April, rectifying the missed opportunity at the G7 summit.

“Everybody understands that the attack against Ukraine is an attack against us as well. Ukraine belongs to Europe.”

Though details of the meeting are scarce, Trump left the talk uncharacteristically critical of Russian leader Vladimir Putin.

Responding to a journalist during a press conference, the U.S. president acknowledged it is “possible” Putin may have territorial ambitions beyond Ukraine – a rare admission for Trump, who always professed his trust in the Russian leader.

"I consider him (Putin) a person I think is misguided," Trump said.

"I think it’s a great time to end it (war). I’m going to speak to Vladimir Putin, see if we can get it ended," Trump added. "He (Zelensky) is fighting a brave battle, it's a tough battle."

President Volodymyr Zelensky (L) and U.S. President Donald Trump (R) meet during the NATO Summit in The Hague, Netherlands, on June 25, 2025. (Zelenskiy / Official Telegram Account / Handout / Anadolu via Getty Images) Trump also carefully signaled support for sending Ukraine additional missiles for Patriot air defense systems, though no concrete commitment was made. Asked about further air defense assistance by a Ukrainian journalist whose husband is a soldier fighting in Ukraine, Trump, in a rare show of sympathy toward Ukrainians, acknowledged her distress over Russia’s escalating aerial attacks.

"They (Ukraine) do want to have the anti-missile missiles, as they call them, the Patriots, and we're going to see if we can make some available," Trump said.

Other NATO leaders reaffirmed their steadfast support for Ukraine as it continues to resist Russia’s full-scale invasion, now in its fourth year.

“Everybody understands that the attack against Ukraine is an attack against us as well. Ukraine belongs to Europe,” Estonian Foreign Minister Margus Tsakhna told the Kyiv Independent during an interview at the summit.

Zelensky’s rhetoric was focused on pressuring Russia to accept a just peace and on raising more international funding for the Ukrainian defense industry.

Individual countries and other partners responded. The Netherlands and Norway pledged hundreds of millions to the Ukrainian defense industry, while the EU confirmed that its new, ambitious $175-billion SAFE defense spending program will be open to Kyiv.

But as the summit unfolded, it became increasingly clear that the spotlight is on Trump.

Putin insists the Russian economy is fine, but Kremlin officials say otherwiseIn a rare public sign that all is not well in Russia, two high-ranking Moscow officials last week issued separate warnings about the state of the country’s economy. Russian Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina and Economy Minister Maxim Reshetnikov both highlighted that amid the Kremlin’s full-scale war against Ukraine, the tools Moscow once relied on to maintain wartime growth are nearly exhausted. Almost immediately, Russian President Vladimir Putin on June 20 dismissed the concerns, clai The Kyiv IndependentTim Zadorozhnyy

The Kyiv IndependentTim Zadorozhnyy

Charm offensive, aimed at TrumpTo say that The Hague summit took place at a precarious moment would be an understatement.

NATO is gripped by what is arguably its greatest existential crisis yet, and the most challenging security situation since the Cold War.tes

Since taking office, Trump has signaled plans to reduce military presence in Europe and cast doubt on his commitment to Article 5 – including just before his trip to the summit.

As Trump’s attention wanders away from Europe and Ukraine to the Israel-Iran conflict and other regions, Europeans are left to grapple with the fears that they might have to face Russian aggression on their own.

“Mr President, dear Donald, Congratulations and thank you for your decisive action in Iran, that was truly extraordinary, and something no one else dared to do. It makes us all safer.”

Perhaps that is why NATO leaders were so dead set on bringing Trump to the summit.

As the Kyiv Independent learned from a Ukrainian official, member countries pulled out all the stops to get Trump to attend, giving him a king’s treatment during the dinner and keeping the summit deliberately short.

Leading this charm offensive was the secretary general himself.

U.S. President Donald Trump (R) and NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte (L) speak to media at the start of the second day of the 2025 NATO Summit in The Hague, Netherlands, on June 25, 2025. (Andrew Harnik / Getty Images)

NATO heads of state and government pose for an official photo on the second day of the 2025 NATO Summit in The Hague, Netherlands, on June 25, 2025. (Omar Havana / Getty Images) “Mr President, dear Donald, Congratulations and thank you for your decisive action in Iran, that was truly extraordinary, and something no one else dared to do. It makes us all safer,” Rutte wrote in a message to Trump ahead of the summit, which the U.S. president promptly published.

“Europe is going to pay in a BIG way, as they should, and it will be your win,” he continued, referring to an agreement to raise the defense spending benchmark to 5% of GDP in a style strikingly similar to Trump’s.

Asked by a journalist whether the revelation of this text was not embarrassing for him, Rutte only doubled down, jokingly referring to Trump as a “daddy” during a briefing.

The summit’s focus on defense spending was likely a deliberate offering to Trump, who has lambasted European allies as underpaying freeloaders. When Rutte managed to get a unanimous agreement on the new spending target despite protests from Spain, he had a big win to present to Trump.

"Your leadership on this has already produced $1 trillion in extra spending from European allies since 2016. And decisions today will produce trillions more for common defense,” Rutte told Trump during the summit.

Trump has not been alone in this criticism. NATO’s eastern members, who devote considerably more to defense than their western and southern partners, echoed the sentiment.

“I totally agree with President Trump… Europe must pay more, Europe must take more responsibility for its own defense,” Tsakhna said.

“Europe has been like an old, lazy cat who was just waiting for something bad to happen, and the U.S. would come and solve the problems.”

Rutte's strategy seemed to have paid off. Trump appeared in good spirits, praising the new defense pledge while enjoying a flurry of questions from journalists that, in the absolute majority, focused on recent U.S. strikes on Iran.

Trump also signed off on the final statement that reaffirmed commitment to Article 5, mollifying his earlier comments.

Ukraine sidelinedWhile the final communique of the NATO summit in Washington last year was 38 paragraphs long, with six devoted to support for Ukraine, this year’s joint declaration was a mere five paragraphs.

The document did name Russia as a threat to the Euro-Atlantic security and reaffirmed support for Kyiv, but stopped short of condemning Moscow, mentioning Ukraine’s NATO aspirations, or offering any concrete new assistance.

This did not come as a surprise. Already in the runup to the summit, Bloomberg reported that the joint communique would omit these topics to avert friction with the U.S. president, who has been averse to offending Russia.

Rutte used the summit to repeat the familiar pledge that Ukraine’s path toward NATO is “irreversible,” but it was obvious that Kyiv’s accession, openly opposed by Trump, would not see any development in the near future.

Even as Russia launched a brutal aerial attack against Dnipro during the summit, which killed 19 people and injured 300, NATO offered Ukraine little but words.

The aftermath of a Russian ballistic missile attack damaged a passenger train in Dnipro, Ukraine, on June 24, 2025. (Serhii Lysak / Telegram) What Ukraine received at this year’s NATO summit was a far cry from the bold pledges made last year in Washington.

But the meeting passed without any visible friction between Trump and his Ukrainian and European partners, with Ukraine even grabbing a few modest wins.

In the era of Trump, that might be a success of itself.

Asami Terajima contributed to reporting.Note from the author:

Hi, this is Martin Fornusek. I hope you enjoyed this article. If you want to help us continue covering crucial events like the NATO summit in The Hague, please consider becoming our member.

Thank you very much.

-

Diplomacy or deal-making? Unpacking the U.S.-Belarus prisoner deal

After a high-level U.S. visit to Belarus led to the release of 14 prisoners, observers have been left wondering what autocrat Alexander Lukashenko may have secured in return.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s special envoy to Ukraine and Russia Keith Kellogg’s visit to Minsk on June 21 marked the highest-level diplomatic contact the isolated regime of Alexander Lukashenko had with the U.S. in years.

The trip was also marked by the freeing by the Lukashenko regime of 14 prisoners, including one of the most notable of Lukashenko’s political opponents — Siarhei Tsikhanouski.

With the released prisoners in the spotlight, both parties to the negotiations were vague regarding the results of the meeting. But members of the Belarusian opposition in exile and political analysts all agreed Lukashenko was seeking some form of international legitimacy, as well as sanctions relief.

“For Lukashenko, the visit is a fairly strong legitimizing step,” said Lesia Rudnik, the director of an exiled independent Belarusian think tank, the Center for New Ideas.

“I believe we’re at the beginning of a dialogue … but I think we’ll see a rather slow development of the situation.”

Lukashenko has been ostracized by the West over his support for Russia’s war against Ukraine and brutal suppression of freedoms in Belarus. His international contacts have been limited to China, Vietnam, Iran, and African states that have minimal trade turnover with Belarus, and, increasingly, local Russian officials. The only Western nations that have thus far broken the diplomatic freeze are Russia-sympathetic EU states Hungary and Slovakia.

As for the U.S., analysts suggest Washington could have been looking to deter deeper Belarusian involvement in the war, while also possibly securing a foreign policy win for Trump amid stalled peace negotiations between Kyiv and Moscow.

Carefully choreographed breakthroughThe trail to Kellogg’s top-level meeting in Minsk was blazed nearly a year ago under the administration of former U.S. President Joe Biden, with low-profile behind-the-scenes meetings and occasional prisoner releases.

The most tangible result of Kellogg’s mission was the sudden freeing of 14 prisoners, including Tsikhanouski, former RFE/RL journalist Ihar Karnei, and citizens of Estonia, Latvia, and Poland, who were released from prisons in Belarus and delivered to neighboring Lithuania. U.S. President Donald Trump marked the release with a celebratory post on his social media platform, Truth Social.

“President Trump now has the power and opportunity to free all political prisoners in Belarus just like that. And I ask him to do so.”

Once seen as an unlikely candidate for early release, Tsikhanouski was freed after serving five years of a nearly 20-year sentence. Jailed ahead of Belarus’s 2020 presidential election, his arrest prompted his wife, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, to run in his place. Despite election observers finding she had won the election, Lukashenko claimed victory, sparking mass protests in Belarus that lasted for months.

At a press conference in Vilnius following his release, Tsikhanouski appealed to Trump to help free other political prisoners in Belarus.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya holds a photo of her jailed husband Siarhei Tsikhanouski as other demonstrators display images of Belarusian opposition figures Maria Kalesnikava and Viktar Babaryka during a protest in front of the Belarusian Embassy in Vilnius, Lithuania, on March 8, 2024. (Petras Malukas / AFP via Getty Images) “President Trump now has the power and opportunity to free all political prisoners in Belarus just like that. And I ask him to do so,” Tsikhanouski said.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who, since being forced into exile, has led the Belarusian opposition, hailed the releases, pledging to “continue to work closely with President Trump’s administration and with all our allies on both sides of the Atlantic to achieve the freedom of every political prisoner.”

European leaders, including EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, European Parliament President Roberta Metsola, Polish Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski, and others, also welcomed the U.S. diplomatic efforts and the freeing of the political prisoners.

Following four years of continuous, harsh repression, Lukashenko suddenly pardoned 18 political prisoners in July 2024, then continued to release small batches of political prisoners every month for half a year. Tsikhanouski said he had heard talk of his potential release in August 2024.

In February, U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Christopher W. Smith made an unannounced visit to Belarus, securing the release of a U.S. citizen and two Belarusian political prisoners.

John Coale, Kellogg’s deputy, during a low-profile visit to Minsk in May facilitated the release of dual U.S.-Belarusian citizen Yuras Ziankovich. The earlier contacts paved the way for Kellogg’s high-profile visit, accompanied by Smith and Coale.

The publicity surrounding the visit indicates that the parties “have reached a minimum level of mutual trust,” commented Valery Kavaleuski, a former Belarusian diplomat and ex-member of Tsikhanouskaya’s shadow cabinet. He is currently advocating for the release of political prisoners as the head of the Euro-Atlantic Affairs Agency.

Restoring ties?One thing Belarusian officials did signal was that they expect more in return, including full restoration of bilateral ties and sanctions relief.

Belarus’s permanent representative to the United Nations, Valentin Rybakov, on state-owned Belarusian television after the Kellogg meeting, said that Minsk seeks to “normalize” bilateral relations with the U.S., which would entail the full resumption of embassy operations in both countries and exchanges of visits by officials.

Alexander Lukashenko (C) meets with U.S. presidential envoy Keith Kellogg and members of the American delegation in Minsk, Belarus, on June 21, 2025. (X/Keith Kellogg) The U.S. withdrew its diplomats and shut down embassy operations in Minsk in February 2022, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which involved the use by the Russian military of Belarusian territory. According to Kavaleuski, the reopening of the embassy lies within U.S. interests in observing and gathering information on the ground. Reopening at the Charge d'Affaires level, as opposed to the ambassadorial level, does not imply any formal recognition of Lukashenko’s legitimacy.

“Without Europe's participation, the ‘de-isolation’ of the Belarusian regime will not be as effective.”

On sanctions relief, Rybakov and Natallia Esismant, Lukashenko’s press secretary, noted that this had been among the priority topics of the discussion. The New York Times also reported that the matter was discussed during Khristopher Smith’s visit to Belarus in February.

“According to our information, Lukashenko is setting a condition for the lifting of the American sanctions on (potash producer) Belaruskali,” opposition activist and leader of the People’s Anti-Crisis Management initiative, Pavel Latushka, told the Kyiv Independent.

“The second is the financial sector, which enables financial payments,” he added. “The third is the Belavia (…) aircraft fleet, which includes (Lukashenko’s) planes.”

In 2019, before Belarus spiraled into political turmoil, potash, its top export, brought in approximately $2.9 billion in export revenues. After the EU and U.S. export restrictions were put in place, Belarus’s share of the global potash market dropped from 18% in 2021 to 8% in 2023, according to the International Food Policy Research Institute. Around 5% of the market was lost in the United States.

“But without Europe's participation, the ‘de-isolation’ of the Belarusian regime will not be as effective,” Rudnik from the Center for New Ideas told the Kyiv Independent, noting that while the U.S. can cancel its own sanctions, Washington would have to lobby for their relief in Europe.

Analysts agree that to restore the flow of this crucial export, Belarus needs to ease European sanctions and overcome opposition from Lithuania, home to Klaipeda seaport, formerly the chief transit hub for Belarusian potash.

Initially introduced in 2021 for human rights abuses, European sanctions on Belarusian potash were re-qualified as sanctions for Minsk’s support for Russia’s war against Ukraine, making them impossible to cancel until the war ends, former diplomat Kavaleuski says, citing his recent exchanges in Brussels.

Belarus, in contrast, expects reciprocal steps and a "good-neighborly approach” after releasing citizens of Estonia, Latvia, and Poland, said Belarus’s KGB Chief Ivan Tsertsel on state-run media, in an apparent reference to European opposition to sanctions relief. Notably, no Lithuanian citizens were included in the release.

But the European Union has so far shown no inclination to reduce restrictions on Lukashenko. Quite the opposite: the 18th sanctions package, recently blocked by Hungary and Slovakia, proposes to ban all transactions with Belarusian banks, further tightening restrictions against Belarus.

"It’s Lukashenko who pushes Belarus closer to Russia because it’s comfortable for him."

And Lithuania, one of the EU member states with the strongest voice on the Belarusian issue, sees no grounds for reconsidering sanctions yet, according to Lithuanian Foreign Minister Kęstutis Budrys. Aware of the potential for a veto by Hungary or Slovakia on Europe-wide sanctions, the Baltic state is developing legislation for national economic sanctions that would provide for the introduction of personal and sectoral restrictions.

While thankful for the release and hopeful for more good news, the Belarusian opposition is cautious about rewarding the regime too soon.

Russian President Vladimir Putin (C), Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko (L), and State Duma Chairman Vyacheslav Volodin (R) attend the Great Heritage – Common Future Forum in Volgograd, Russia, on April 29, 2025. (Contributor / Getty Images) “Naturally, if the repression stops, and all the prisoners are released, it would open new possibilities, and one could talk about certain relief from the American sanctions,” Tsikhanouskaya’s advisor Viachorka says, adding that at this point, only 1.5% of the country’s 1,100 political prisoners have been released through U.S. mediation.

“There’s no trust in Lukashenko,” said exiled activist Latushka, who is known for his more hawkish approach to contacts with the Lukashenko regime.

“Over the 30 years of his rule, Lukashenko has repeatedly used this scheme of easing sanctions by making cosmetic concessions to the West.”

Latushka argues that sanctions should be eased only after the release of all political prisoners, a halt to repression, and the decriminalization of political life within the country. Even after that, restrictions should be suspended but not cancelled to ensure the possibility of swift reinstatement in case of backsliding by Minsk, he said.

But having released 14 prisoners, Belarusian KGB Chief Tsertsel reported that another 14 foreign and Belarusian citizens had been arrested in Belarus on charges of espionage and high treason in 2025 — in a sign the regime's "conveyor belt" of repression has far from slowed down.

Washington's interest in MinskFollowing his visit to Minsk, Kellogg shared that while his deputy John Coale led discussions on the release of prisoners, he had focused on the Russia-Ukraine War.

“We know Trump is, first and foremost, a dealmaker, and secondly, that success is important to him,” Rudnik said of the interest of the Trump administration in dealing with Belarus.

“And when this does not happen for a long time, especially when he promised so much in his election campaign, it becomes necessary to compensate for the lack of these victories with smaller victories, perhaps even a lot of them,” she said.

Observers interviewed by the Kyiv Independent do not believe Belarus could serve as a credible platform for the stalled Russian-Ukrainian peace negotiations — an idea that has been floated by the Kremlin, but flatly rejected by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky over Belarus's complicity in the war.

U.S. President Donald Trump at the White House in Washington, DC, on June 10, 2025. (Saul Loeb / AFP via Getty Images) While not having sent his troops into battle in Ukraine, Lukashenko let the Russian army use Belarusian territory to mount attacks on Ukraine at the start of the invasion. He also reoriented the Belarusian military-industrial complex to serve Russian defense contracts, according to a recent report by the Belarusian opposition group Belpol.

Aside from “scoring a win” easier than stopping Russia’s war, Washington may have warned Belarus against becoming more deeply engaged in the Kremlin’s war against Ukraine, or escalating tensions with the NATO and EU member states bordering Belarus, analysts suggest.

“Belarus is strategically placed on NATO’s eastern flank between Russia and western states,” Tsikhanouskaya’s advisor Viachorka says. “The less of a threat Belarus is, the less defense spending for America.”

Belarus is set to host the Zapad-2025 (West 2025) joint military drills with Russia in September. After the Russia-Belarus Union Resolve 2021 drills were used to disguise the buildup of Russian troops ahead of an all-out invasion, any joint drills in Belarus are now seen as a serious cause for concern among its neighbors.

In an apparent effort to assuage those fears, in May, Belarusian Defense Minister Viktar Khrenin announced the drills would involve fewer troops and would be held at a location further from the border.

The Kellogg visit, Latushka believes, also had the aim of determining whether Lukashenko is capable of altering his domestic or foreign policy, and the extent of the Kremlin’s influence over him.

Americanist and advisor to the Euro-Atlantic Affairs Agency Anton Penkovski told the Kyiv Independent that the Trump administration might be considering the possibilities for the “Finlandisation” of Belarus, a term that implies Minsk would loosen its military ties with Moscow without fully breaking off ties.

And while having nothing to lose in the event of negotiations failing, U.S. diplomats might also have been investigating Lukashenko’s ability to act independently and engage in separate negotiations in the event of Russia being weakened.

Indeed, Washington has a history of engaging with Minsk at times when tensions with Moscow heighten.

Viachorka, however, is not so sure.

“We often hear the message that we need to save Lukashenko from Russia, including from Belarusian propaganda,” he says. “But it’s Lukashenko who pushes Belarus closer to Russia because it’s comfortable for him.”

Subscribe to the NewsletterBelarus Weekly<span data-sanitized-id="belarus-weekly-info" data-sanitized-class="belarusWeekly__info"></span> <button data-sanitized-id="belarus-weekly-subscribe-btn" data-sanitized-class="belarusWeekly__form_button"> <span data-sanitized-class="belarusWeekly__form_label">Join us</span> <path d="M4.45953 12.8114H7.90953C8.00052 12.8127 8.09085 12.7958 8.17517 12.7616C8.25949 12.7274 8.3361 12.6766 8.40044 12.6123C8.46478 12.548 8.51556 12.4714 8.54975 12.387C8.58395 12.3027 8.60088 12.2124 8.59953 12.1214C8.58173 11.9269 8.48974 11.7467 8.34265 11.6183C8.19555 11.4898 8.00465 11.4229 7.80953 11.4314H4.45953C4.27653 11.4314 4.10103 11.5041 3.97163 11.6335C3.84223 11.7629 3.76953 11.9384 3.76953 12.1214C3.76953 12.3044 3.84223 12.4799 3.97163 12.6093C4.10103 12.7387 4.27653 12.8114 4.45953 12.8114Z" fill="white"></path> <path d="M8.6 15.0114C8.60135 14.9204 8.58442 14.83 8.55022 14.7457C8.51603 14.6614 8.46525 14.5848 8.40091 14.5205C8.33656 14.4561 8.25996 14.4053 8.17564 14.3711C8.09131 14.3369 8.00098 14.32 7.91 14.3214H2.69C2.507 14.3214 2.3315 14.3941 2.2021 14.5235C2.0727 14.6529 2 14.8284 2 15.0114C2 15.1944 2.0727 15.3699 2.2021 15.4993C2.3315 15.6287 2.507 15.7014 2.69 15.7014H7.81C8.00511 15.7099 8.19602 15.643 8.34311 15.5145C8.49021 15.386 8.5822 15.2058 8.6 15.0114Z" fill="white"></path> <path d="M24.4202 6.01122H7.55022C7.43403 5.99626 7.31641 5.99626 7.20022 6.01122L7.08022 6.06122C6.85578 6.16602 6.66595 6.33276 6.53308 6.54181C6.4002 6.75086 6.32982 6.99352 6.33022 7.24122C6.32744 7.43266 6.36832 7.62222 6.44976 7.79549C6.5312 7.96876 6.65105 8.1212 6.80022 8.24122L12.5802 13.4512L6.89022 18.7112C6.71923 18.8375 6.57973 19.0016 6.4826 19.1907C6.38546 19.3797 6.33331 19.5887 6.33022 19.8012C6.32652 20.0535 6.3952 20.3015 6.52812 20.516C6.66105 20.7304 6.85264 20.9023 7.08022 21.0112C7.14691 21.0484 7.21729 21.0786 7.29022 21.1012C7.46476 21.1609 7.64625 21.1979 7.83022 21.2112H24.5102C24.8263 21.2048 25.1378 21.1355 25.4268 21.0074C25.7158 20.8792 25.9763 20.6948 26.1932 20.4648C26.4101 20.2349 26.579 19.9641 26.6901 19.6681C26.8012 19.3722 26.8522 19.0571 26.8402 18.7412V8.47122C26.8278 7.82952 26.5701 7.21694 26.12 6.7594C25.6699 6.30185 25.0616 6.03412 24.4202 6.01122ZM8.57022 8.08122L7.92022 7.49122H24.4202L16.4902 14.6812C16.407 14.7305 16.312 14.7565 16.2152 14.7565C16.1185 14.7565 16.0235 14.7305 15.9402 14.6812L8.57022 8.08122ZM7.73022 19.7912L8.48022 19.1112L13.4802 14.5812L14.8802 15.8612C15.1804 16.157 15.5793 16.3315 16.0002 16.3512C16.4212 16.3315 16.82 16.157 17.1202 15.8612L18.5202 14.5812L24.2002 19.8012H7.73022V19.7912ZM25.3502 18.7112L19.6602 13.5912L25.3502 8.37122V18.7112Z" fill="white"></path> </button> </div>Why Russian economy warnings might be the only thing out of Moscow you can actually believeIn a rare public sign that all is not well in Russia, two high-ranking Moscow officials last week issued separate warnings about the state of the country’s economy. Russian Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina and Economy Minister Maxim Reshetnikov both highlighted that amid the Kremlin’s full-scale war against Ukraine, the tools Moscow once relied on to maintain wartime growth are nearly exhausted. Almost immediately, Russian President Vladimir Putin on June 20 dismissed the concerns, clai The Kyiv IndependentTim Zadorozhnyy

The Kyiv IndependentTim Zadorozhnyy

As Ukraine bleeds, Western opera welcomes back pro-Putin Russian singer Anna Netrebko

More than three years into Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, many Western cultural institutions that had distanced themselves from Russian artists as a gesture of solidarity with Ukraine are now reversing course.

The U.K.’s Royal Ballet and Opera House announced on June 23 that its 2025-2026 cinema season, which is screened across 1,500 cinemas around the world, will kick off in early October with a performance of “Tosca” starring Russian soprano opera singer Anna Netrebko.

Once a leading figure in the opera world, Netrebko saw her performances canceled after 2022, following a history of remarks where she praised Russian President Vladimir Putin and defended Russian imperialism.

Though she issued a statement condemning the full-scale invasion that year, Netrebko has stopped short of ever directly criticizing Putin, who granted her Russia’s highest artistic honor — the title of People’s Artist — in 2008.Since the start of the full-scale invasion, many Ukrainians have argued that Russian culture can’t be separated from the country’s history of imperialism — a worldview they say is deeply embedded in its literature, music and art, and continues to fuel its aggression toward Ukraine and beyond.

What’s wrong with NetrebkoFollowing Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Metropolitan Opera in New York canceled a series of scheduled performances by Netrebko, reportedly expecting her to publicly denounce Putin.

In response, Netrebko filed a lawsuit in 2023 seeking at least $360,000 in damages and accusing the Met of defamation and breach of contract.

While she spoke out against the full-scale war in a statement from May 2022, Netrebko also declared “I love my homeland of Russia and only seek peace and unity through my art.”

Netrebko has repeatedly expressed views and took actions prior to 2022 that signaled admiration — even support — for the Russian authoritarian regime.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, conductor Valery Gergiev, and singer Anna Netrebko attend the opening of the new Mariinsky II Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, on May 2, 2013. (Sasha Mordovets / Getty Images) “I think she is always doing what benefits her career. Until 2022, being Putin’s ‘court soprano’ and a protege of conductor Valery Gergiev — another pillar of the Kremlin’s influence in the world, who was sanctioned by the government of Canada just few days ago — was very good for her,” Ukrainian classical pianist Pavlo Gintov, who lives and performs in the West, told the Kyiv Independent.

“Since 2022, Netrebko has been trying to balance two worlds: continuing her performances in the West while avoiding an open break with Putin’s regime. And, as you can see, so far she has been quite successful.”

After Russia’s invasion of Georgia, Netrebko told Russian state media in 2009, “I am always unambiguously for Russia,” dismissing international coverage of the war as “extremely negative” attacks on her country.

While Western cultural institutions rekindle ties with Russian artists, Ukrainian artists continue to be killed.

In a Newsweek profile from 2011, Netrebko laughed off rumors from the Russian tabloids claiming she had been Putin’s lover, adding “I’d love to have been” and that “he’s a very attractive man” with “strong, male energy.”

In 2014, Netrebko made a donation of one million rubles to an opera house in Russian-occupied Donetsk, claiming it was an act of solidarity for her fellow artists suffering from the war and that there was nothing political about it.

However, she was photographed alongside Oleg Tsaryov, a pro-Russian Ukrainian politician, at the event in St. Petersburg where she made the donation. Both were seen holding the flag of the Russian occupation forces in Donetsk.

Putin praised Netrebko's "life-affirming spirit" and "clear civic stance" in a public tribute marking her 50th birthday in 2021 that was published on the Kremlin's website.

“Only a photo with the bandits and their Moscow handlers could be a better illustration of the global disgrace of the Royal Opera House,” wrote Ukrainian Foreign Minister Sergiy Kyslytsya on June 24 on X, formerly known as Twitter, referencing the notorious photo in response to the Royal Opera House’s lineup announcement.

Azerbaijani opera singer Yusif Eyvazov and Russian opera singer Anna Netrebko, perform on stage at the Thurn & Taxis Castle Festival in Regensburg, Germany, on July 23, 2022. (Isa Foltin / Getty Images)

People protest against opera singer Anna Netrebko's appearance at the Schlossfestspiele in Regensburg, Bavaria, Germany, on July 22, 2022. (Ute Wessels / Picture Alliance via Getty Images) Larger trendNetrebko’s return to Western opera marks a tentative shift in the West’s cultural landscape, as institutions begin to welcome Russian artists back more than three years after their country’s full-scale war against Ukraine cast a long shadow over their global standing.

Among these cultural figures are those who support Putin outright, those who oppose the war, or those who are deliberately trying to blur the line between the two.

As Western institutions move toward reintegrating Russian cultural figures into their cultural programs, Moscow has intensified its military campaign against Ukraine, launching record numbers of drones and missiles with increasing frequency, causing greater casualties.

This thaw raises ethical questions about complicity and accountability, such as when Russian actor Yura Borisov’s 2024 Oscar nomination for best supporting actor in the film “Anora.”Previously, Borisov starred in a Russian propaganda biopic about Mikhail Kalashnikov, the inventor of the AK-47, which was filmed in Russian-occupied Crimea and released in 2020.

Though Borisov’s name appeared on a 2022 statement by a Russian film actors’ union opposing the full-scale war, he didn’t mention it once during his major press tour for “Anora.”

(L-R) Russian actor Yura Borisov, Mikey Madison, and Mark Eydelshteyn speak onstage during the 31st Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards at Shrine Auditorium and Expo Hall in Los Angeles, California, U.S. on Feb. 23, 2025. (Matt Winkelmeyer / Getty Images) Russian journalist Anastasia Trofimova also stirred outrage for her documentary “Russians at War,” which she claimed was meant to “humanize” Russian soldiers fighting in Ukraine “beyond the fog of war.”

Ukrainians and their supporters sought to have the film removed from several international film festivals due to Trofimova’s previous involvement with Russian state media and the documentary’s attempt to dissociate Russian soldiers from war crimes committed in Ukraine. Despite these efforts, a number of screenings have taken place.

The film was screened at three festivals in Canada, and although it was pulled from a number of other international festivals over protests, it remained in competition at the Athens International Film Festival in 2024.At the 2025 Photo London Festival, Russian fashion designer and photographer Gosha Rubchinsky presented his new photo book, “Victory Day,” which romanticizes Soviet army imagery that has been used to rally support amid Russians for the war against Ukraine.

While Western cultural institutions rekindle ties with Russian artists, Ukrainian artists continue to be killed — whether in Russia’s daily strikes on cities or while serving on the front line — underscoring the war’s unrelenting toll on Ukraine’s cultural life.For many Ukrainians, the inclusion of Russian cultural figures in the West is extremely painful, Gintov said — an oversight that ignores the painful reality of a nation still fighting for its survival.

“All this is happening while Russian artists like Netrebko — who openly and vocally supported Putin’s policies for many years, including his invasion of Ukraine in 2014 — are gaining applause in Berlin and in London. Something is fundamentally wrong about it.”Note from the author:

Hi there, it's Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading my latest article. On the same day I wrote this article, I also wrote another about my friend Victoria Amelina, a Ukrainian author who was killed by Russia, posthumously winning a prestigious literary award. It's bitter and surreal to see the world begin to move on from caring about the ways Russian culture and Russian aggression are connected. Of course, this is not to say that every Russian artist is supportive of the war — but in Netrebko's case, there's a lot of past statements that raise troubling questions. If you like reading this sort of thing, please consider supporting us and becoming a member of the Kyiv Independent today.

‘Everyone says culture has nothing to do with it. It does’ — Ukrainian writer Volodymyr Rafeyenko on Russia’s warUkrainian author Volodymyr Rafeyenko never thought he would write a novel in Ukrainian. He was a native of Donetsk, an eastern Ukrainian city where he grew up speaking Russian and completed a degree in Russian philology. Early on in his career, he was the winner of some of Russia’sThe Kyiv IndependentLiliane Bivings

Trump could free all Belarus's political prisoners 'with a single word,' released oppositionist Tsikhanouski says

Siarhei Tsikhanouski, a Belarusian oppositionist recently released from prison, thanked the U.S. on June 22 for brokering his release and appealed to President Donald Trump to help free other political prisoners in Belarus.

“President Trump now has the power and opportunity to free all political prisoners in Belarus with a single word. And I ask him to do so, to say that word,” Tsikhanouski said in Vilnius during his first press conference after the release.