As recently as November, the Indian Ministry of External Affairs reported identifying 44 Indian nationals serving in the Russian armed forces. However, data from the

I Want to Live project suggests the true number is considerably higher. At least 146 Indian citizens have been confirmed by name as having signed contracts, and at least 22 have been killed in action in Ukraine.

Our review of the records indicates that Russia, working through local recruiters in India, is actively targeting Indian nationals, drawing them into military service despite the Indian government’s efforts to curb such cases. In May 2024, India’s Central Bureau of Investigation arrested four individuals involved in trafficking citizens to fight for the Russian army. The suspects were based across multiple Indian cities and had collaborators in Dubai and Russia.

The issue drew national attention after reports surfaced that young Indians were being misled into joining the Russian military under the pretense of work or study visas. Families in Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Telangana said their relatives were pressured or deceived into enlisting as “support staff,” only to be deployed to the front lines.

Earlier this month, relatives from more than ten states, including families of two men killed in the war, staged a protest at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar. They carried signs urging Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Vladimir Putin to intervene.

Table of Contents

Introduction

I. Luring the Recruits

II. Deployment and Casualties

III. Assessment and Summary

Sources

I. Luring the Recruits

One of the major differences compared to our earlier investigation into Cuban recruitment is that the path into the Russian army is far less straightforward. Unlike Cuban mercenaries, who generally know they are signing up to serve in the Russian military, India-focused recruitment offers much less transparency. Our team has verified that, despite requests to halt such activity, the recruitment of Indian nationals remained active as of November 2025, with numerous advertisements promising hassle-free Russian visas, employment, and good pay in civilian sector.

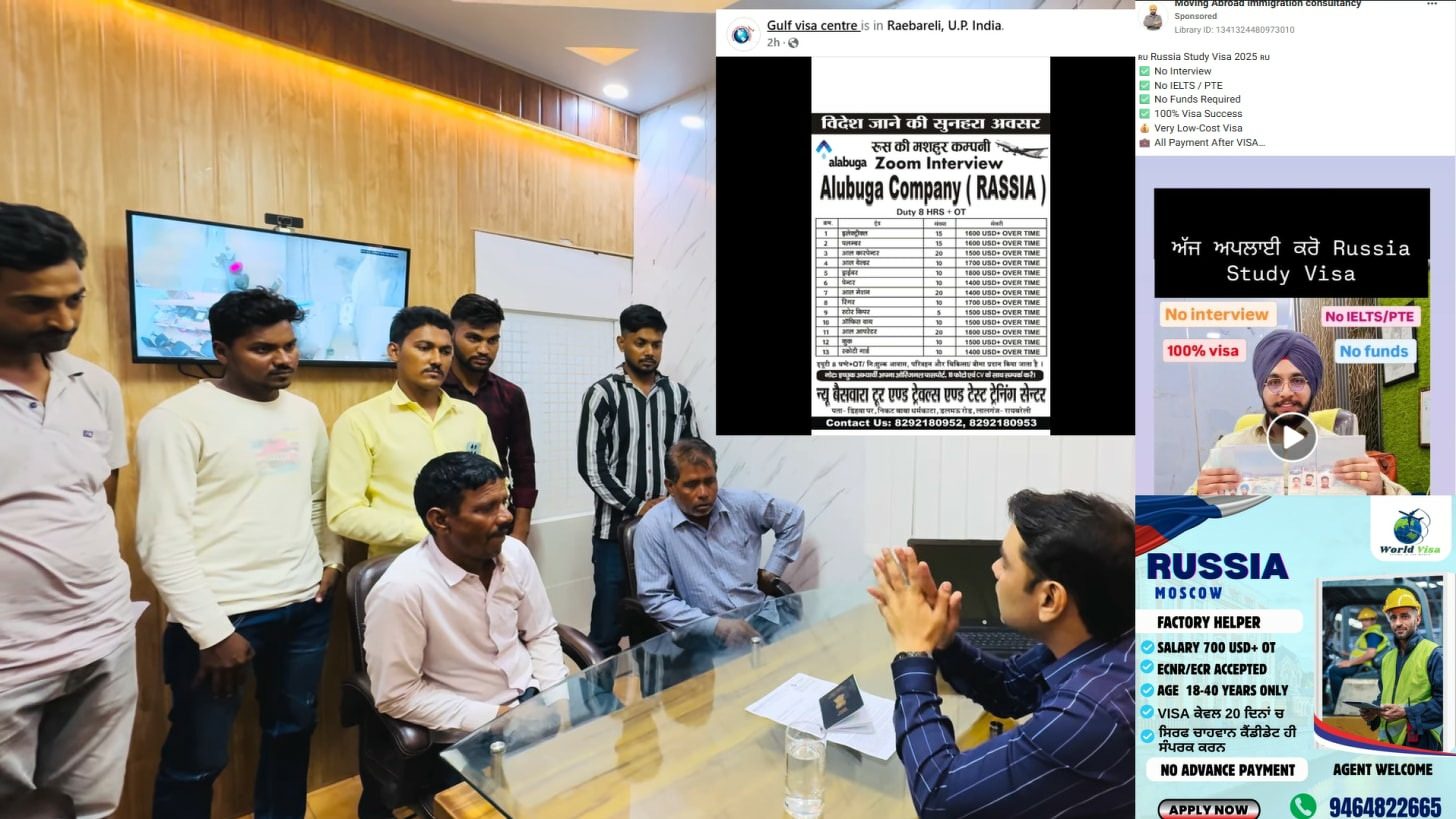

We identified more than a dozen ongoing or recently concluded advertising campaigns targeting Indian citizens. In the compilation image below, you can see examples from Facebook, YouTube, and other social-media platforms promoting lucrative job opportunities. Notably, some advertisements even mention Alabuga, the economic zone where Russians mass-produce drones including Shaheds, while others are more vague about the actual employer.

These offers are especially attractive, promising salaries of $700 to $1,000 per month in Russia, which is roughly double or even triple the average income in India. This makes them particularly appealing to individuals from poorer or rural areas.

Once in Russia, recruits typically face two main paths to enlistment. Some encounter pressure from law enforcement, immigration authorities, or other agencies, and in certain cases are presented with the choice of joining the military or facing legal consequences. Others are lured with promises of visa or citizenship assistance, often with assurances of non-combat roles. Sign-up bonuses can reach tens of thousands of dollars, roughly equivalent to a decade of earnings for an average worker in India.

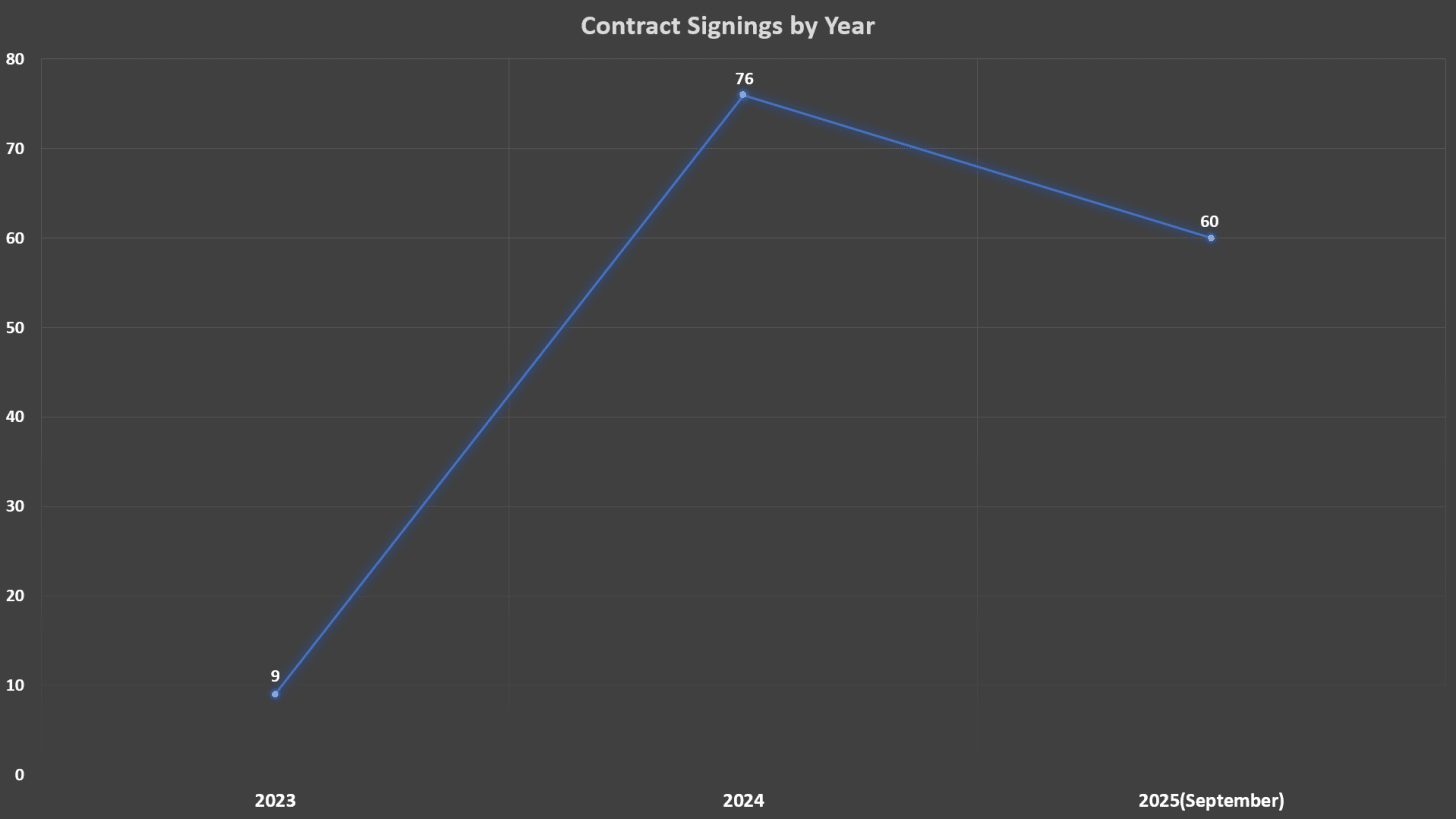

An analysis of 145 verified records shows that in 2023 only nine contracts were signed.

That number rose to 76 in 2024, and by September 2025, 60 contracts had been recorded. This suggests that recruitment levels have remained largely consistent with 2024 despite measures taken by the Indian government. Unlike trends observed in several African countries, there is no clear surge in enlistment.

A source in India, speaking to us on the condition of anonymity, explained that the Indian government is trying to combat this recruitment, but new ads and offers appear quickly through messaging apps, social networks, or even word of mouth, making it difficult to fully stop.

While this list is not exhaustive and the true number of Indian mercenaries fighting for Russia is likely higher, our team concludes that these figures are still far too small to suggest a state-backed mercenary program. By comparison, Cuba, despite having a population more than 120 times smaller than India, has directly supplied thousands of mercenaries to Russia’s armed forces.

II. Deployment and Casualties

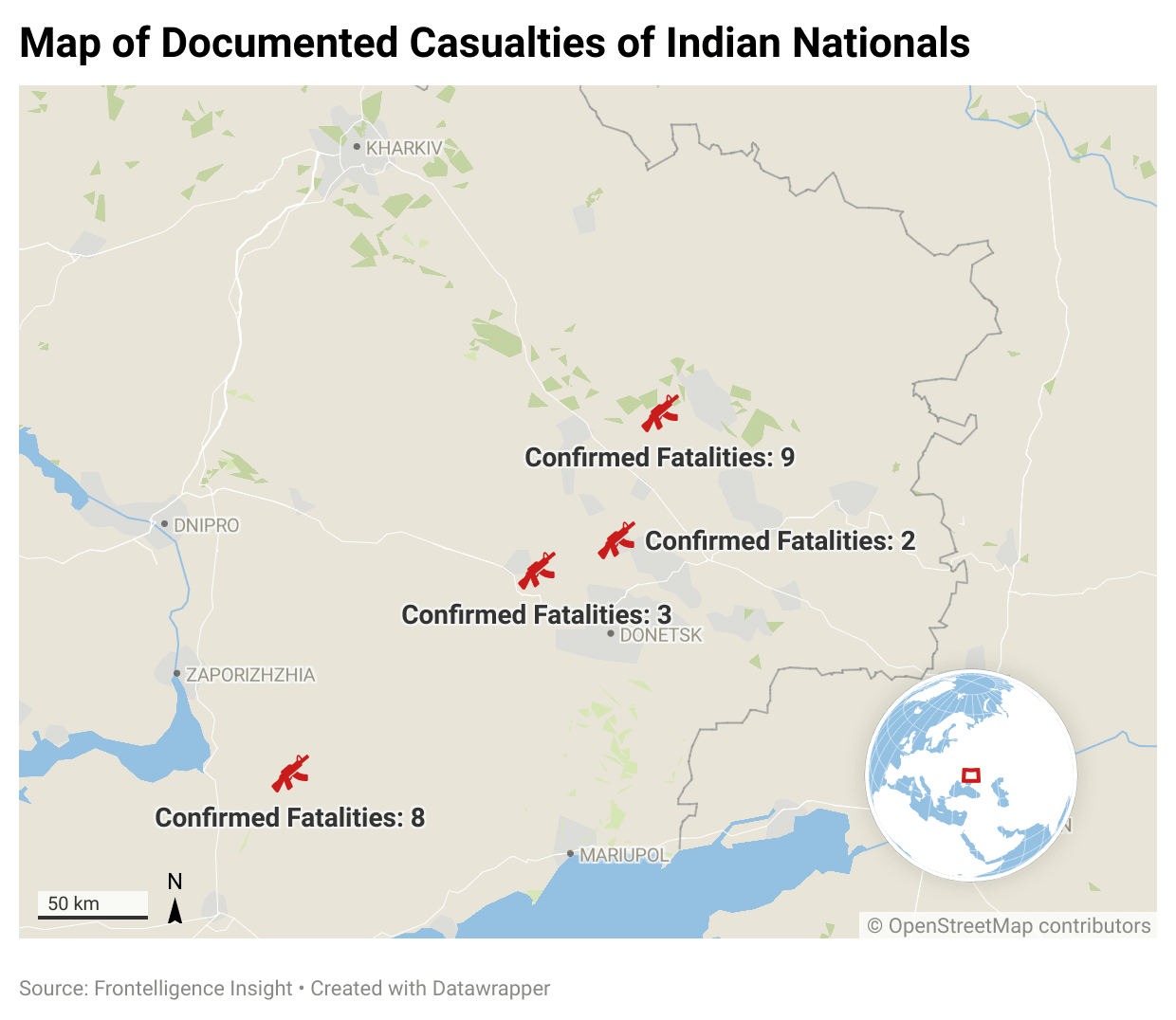

Details about those killed in action help reveal where these mercenaries actually serve. Despite promises of rear-area or logistics duties, they are sent straight to the front. The list of 22 Indian nationals killed in Ukraine shows most losses came from the 7th Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade of the 3rd Army, formed from residents of occupied Luhansk Oblast and long marked by heavy casualties. The brigade has been operating around Bilohorivka for some time.

Earlier, when we examined Egyptian citizens fighting for Russia, we noted similarly high casualty rates in this same sector.

The second largest - 291st Motorized Rifle Regiment, which is advancing towards Orikhiv, near Robotyne area - same area, where Ukrainian counter-offensive commenced in the spring-summer of 2023. The next after that is another unit from the 58th army - 71st motor rifle regiment, which operates in the same axis as 291st regiment - towards Orikhiv.

Notably, just as in case with most of other mercenaries, the median age is lower - whether Russian soldier median age is around 38, the median age of mercenaries from India is 27. Overall, younger personnel are naturally better suited for assault units, where physical demands are far higher. It is therefore unsurprising that they are sent directly to the front lines, not only to preserve Russian troops by using foreign recruits in the most dangerous roles, but also because their physical condition makes them more capable of enduring such assignments.

A common question when foreign fighters are killed is what happens to them afterward. The case of Sonu Kumar, from Hisar, offers a good example. He was among several Indians who travelled to Russia on student visas. According to a report by Firstpost, recruiting agents convinced him to extend his stay with promises of steady, well-paid work.

“Sonu was told he would work as a security guard and be kept far from the war zone,” his brother Vikas said. “He trusted them because they assured him he would earn well and remain safe.”

The family last heard from Kumar on Sept. 3, when he said he was being sent to the front line and that his phone would soon be confiscated.

On Sept. 19, the family received a Telegram message from Russian authorities saying Kumar had gone missing on Sept. 6 and that his body had been found. They were told his remains could be moved to Moscow airport for repatriation, but only if the family covered the costs.

III. Assessment and Summary

When recruits from India, Iraq, China and several other Asian countries are added together, they amount to enough personnel to fill the ranks of an entire motor rifle regiment. The figure is far from decisive in a war of this scale, but it matters for the small, incremental gains Russia continues to make by ensuring it always has enough manpower to keep pushing forward, something Ukraine, unlike Russia, struggles to match.

This approach comes with caveats and costs. Many of the countries involved do not encourage such recruitment, creating diplomatic friction, especially when their citizens are captured by Ukrainian forces. This is an uncomfortable situation for governments trying to maintain neutrality or balance ties with both Kyiv and Moscow. Communication is also a challenge, because foreign volunteers from different linguistic backgrounds often struggle to interact with Russian commanders.

So, while using foreign nationals may reduce Russian casualties at the margins, it carries clear trade-offs. And despite the number of Indian citizens fighting for Russia, our team concluded that, relative to India’s population of more than 1.4 billion, the figures are negligible. This makes state involvement in any such scheme unlikely.

Thank you for reading. A link to the full list of names in English, along with dates of birth, is available to paid subscribers below.

Sources

1. Hochu Zhit (2025). https://hochuzhit.com/en/

2. Al Jazeera. (2024, May 8). India arrests four for duping young men into fighting for Russia in Ukraine. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/5/8/india-arrests-four-for-duping-young-men-into-fighting-for-russia-in-ukraine

3. Times of India. 44 Indians in Russian army: MEA in touch with Kremlin after identification; warns citizens against joining. The Times of India. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/125160882.cms

4. Outsourced war (2025). Frontelligence https://frontelligence.substack.com/p/outsourced-war

5. Firstpost. (2024, February 22). Were Indians duped by agents to fight for Russia in Ukraine war? Firstpost. https://www.firstpost.com/world/indian-men-at-ukraine-war-front-duped-by-agents-fighting-for-russia-moscow-mea-pm-modi-putin-luped-for-jobs-familty-seek-help-13947616.html