Debate about Ukrainian soldiers who go absent without leave and about desertion has intensified, but the scale of the problem is still widely misunderstood. Public discussion leans on speculation because no reliable, unified reporting system exists. How many troops actually desert, how authorities respond, and what happens after they are caught remains unclear even among many Ukrainians.

This report examines one of Ukraine’s most difficult military issues. Desertion and long-term absence have become serious strategic risk, influencing the performance of units across sectors and shaping the course of the war to Ukraine’s disadvantage. Addressing the problem could bring wide improvements, but first requires a clear understanding of the crisis.

Table of Contents:

I. Legal Definitions

1.1 AWOL Under Ukrainian Law

1.2 Desertion vs. AWOL

II. Navigating the AWOL System

2.1 Transfers Through AWOL

III. The Numbers: Scale and Trend

IV. Who Goes AWOL - and Why

V. Why Enforcement Fails

VI. Stricter Penalties or Pragmatic Flexibility?

VII. Band-Aid Fixes vs. Structural Problems

VIII. The Bottom Line

I. Legal Definitions

Understanding Ukraine’s AWOL and desertion problem begins with defining the terms. Under Ukrainian law, Absence Without Leave (AWOL) and desertion are distinct offenses, yet public discourse often blurs the line. Some explanations dismiss AWOL as a minor disciplinary lapse, while others mislabel desertion, creating confusion or exaggerating the scale of the problem. The result is a distorted picture, leaving the public unsure how widespread unauthorized absences actually are and how they affect the war

1.1 AWOL Under Ukrainian Law

Under Article 407 of the Criminal Code, AWOL occurs when a servicemember leaves their unit or duty post without permission for more than three days. Shorter absences are still unauthorized, but they count as disciplinary violations rather than criminal offences and do not enter AWOL statistics.

In practice, most AWOL cases fall into two common scenarios. The first is leaving a unit or duty post without approval. The second is failing to return from leave, medical treatment or official travel on time.

1.2 Desertion vs. AWOL

The legal difference between the two offences is narrow. AWOL, covered by Article 407, and desertion, covered by Article 408, share the same basic act: leaving a unit or duty post without permission. The dividing line is intent. A servicemember commits desertion when the absence is taken with the intention of not returning and of abandoning military service for good. That intent, rather than the duration of the absence or the circumstances in which it happened, is what separates the two crimes in the eyes of Ukrainian law.

For this reason, throughout this report we use the terms “deserter” and “AWOL” largely interchangeably, due to how closely the two offences overlap in practice.

II. Navigating the AWOL System

What does the process look like in practice? Once a soldier is marked as absent without leave, units typically give them several days to return on their own. Most who come back within that window receive only basic disciplinary measures or guidance and are restored to duty. If the soldier does not return, the unit conducts an internal inquiry before sending the case to the State Bureau of Investigation (SBI). The SBI then opens a formal file and prepares it for court, which is the point at which the case enters official statistics.

Soldiers listed as deserters are removed from unit rosters, lose pay and benefits, and cannot receive combat orders.

If police or military law enforcement detain a deserter, the individual is transferred to a reserve battalion, where they remain while their case awaits a court ruling, leaving them stuck in administrative limbo.

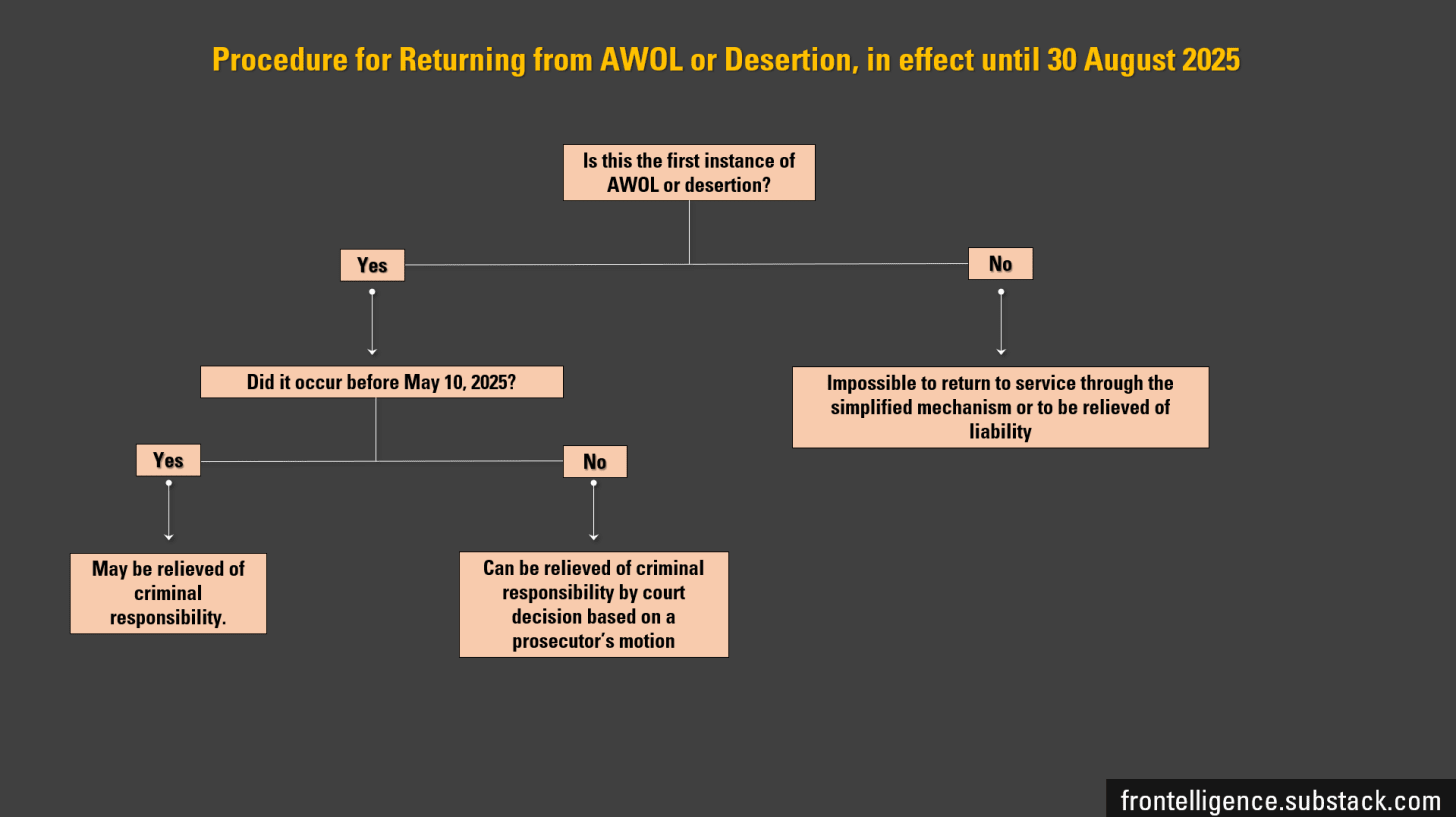

From late 2024 through August 2025, Ukraine’s rules for returning to service after going AWOL under wartime changed several times. On November 29, 2024, legislation took effect that allowed certain first-time AWOL servicemembers a simplified “return to duty” path with restored pay, benefits, and social guarantees.

Under this mechanism, soldiers could file a request to return through the Army+ app. If they reported in person within the required window, they were assigned to a reserve unit, where their contracts were typically reinstated. Pay, rations, clothing and other entitlements were restored, after which they were transferred to an active unit.

The simplified return and transfer option, returning to service and potentially moving to another unit, was formally extended until August 30, 2025. During that period, over 29,000 servicemembers returned under the scheme.

2.1 Transfers Through AWOL

AWOL increasingly became an informal channel for transferring between units. A soldier typically first applied for an official transfer, only to be denied. They would then go AWOL, secure a written recommendation from the receiving unit, and report back to the military. With that document, instead of returning to their original unit, they were reassigned to the new one, effectively completing the transfer. Each of these cases, however, generated a criminal file under Article 407.

Even after a soldier transferred to a new unit, the process was not complete. Criminal cases remained open until a court reviewed them, leaving servicemembers with an unresolved case on the books. While the simplified return mechanism was in effect, commanders could reinstate soldiers even if criminal proceedings were pending, so long as they met the program’s criteria.

In practice, this means that reinstated soldiers who transferred to other units or had already returned to combat after reinstatement still had their cases pending in the system and were counted in general AWOL statistics.

III. The Numbers: Scale and Trend

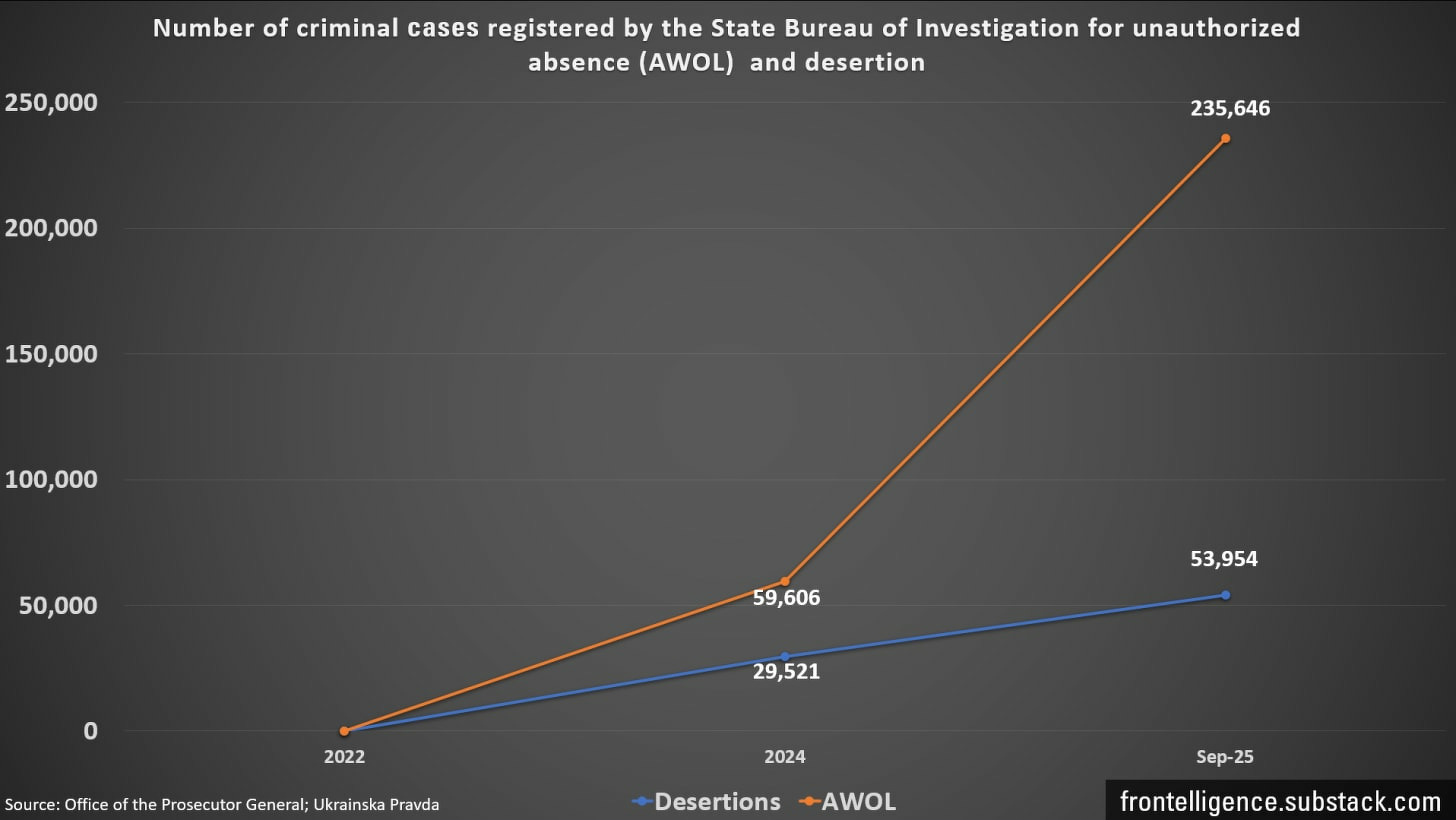

Between January 2022 and September 2024, the SBI opened 59,606 AWOL cases and 29,521 desertion cases. By September 2025, AWOL cases had reached 235,646 and desertion cases 53,954.

This means roughly 200,000 new cases were added in the twelve months after September 2024 alone. The trend points at a sharply worsening situation that accelerated over the past year and, if left unaddressed, could lead to an eventual frontline collapse. At the same time, we should keep in mind that the number of cases is not the same as the number of people involved.

That assumption produces an exaggerated and often catastrophic picture. In reality, the number of servicemembers who went absent without leave is almost certainly about half the commonly cited case totals.

The distortion stems from how cases are recorded and counted, a point explained in detail in the following section.

Although no high-confidence nationwide figure exists, interviews and the limited unit-level data available point to a more realistic estimate of roughly 150,000 deserters combined. The number remains serious, but it is far below the raw case count frequently and incorrectly used as a proxy for the total number of missing servicemembers.

4. Who Goes AWOL - and Why

We determined that the overall case count is an unreliable measure of the number of soldiers who went AWOL, due to the following distortions:

• repeated AWOL by the same individuals

• returnees still waiting for courts to close cases

• returnees held in reserve battalions

• mistaken entries

Officers handling AWOL cases who spoke on the condition of anonymity identified three main categories of servicemembers who go absent: long-serving frontline soldiers, newly mobilized personnel, and a small group affected by administrative errors. Each has their own distinct problems and need tailored approaches to fix:

- Veteran Frontline Soldiers

This group includes troops with more than 18 months on the frontlines, many of whom joined the Ukrainian military in 2022. Their desertions are particularly consequential, as they bring experience, stabilize units, and mentor new recruits. While not the largest category of AWOL or desertion cases, numbers among these soldiers have steadily risen over the past year.

Common reasons include:

Blocked transfers: Soldiers may go AWOL to force a transfer when commanders refuse their official transfer requests.

Family and personal pressures: Years away amplify childcare burdens, spousal issues, and care for elderly parents. Limited rotations or rare visits cannot replace meaningful leave.