Featured Subscriber’s Comment:

“I support this work because it is the most accurate and valuable information and commentary about Ukraine. Authentic voices of serving journalists who work with Tim Mak. And the incredible DNA of fighting for democracy for ALL OF US shines through. Thank you Tim Mak for all you do.”

By: Elizabeth K. Baker

It was October 2022, and Serhii* is staring in dismay at a two-meter-high crater.

He had driven out to the impact site of what was believed to be a missile near a village in the Kyiv region.

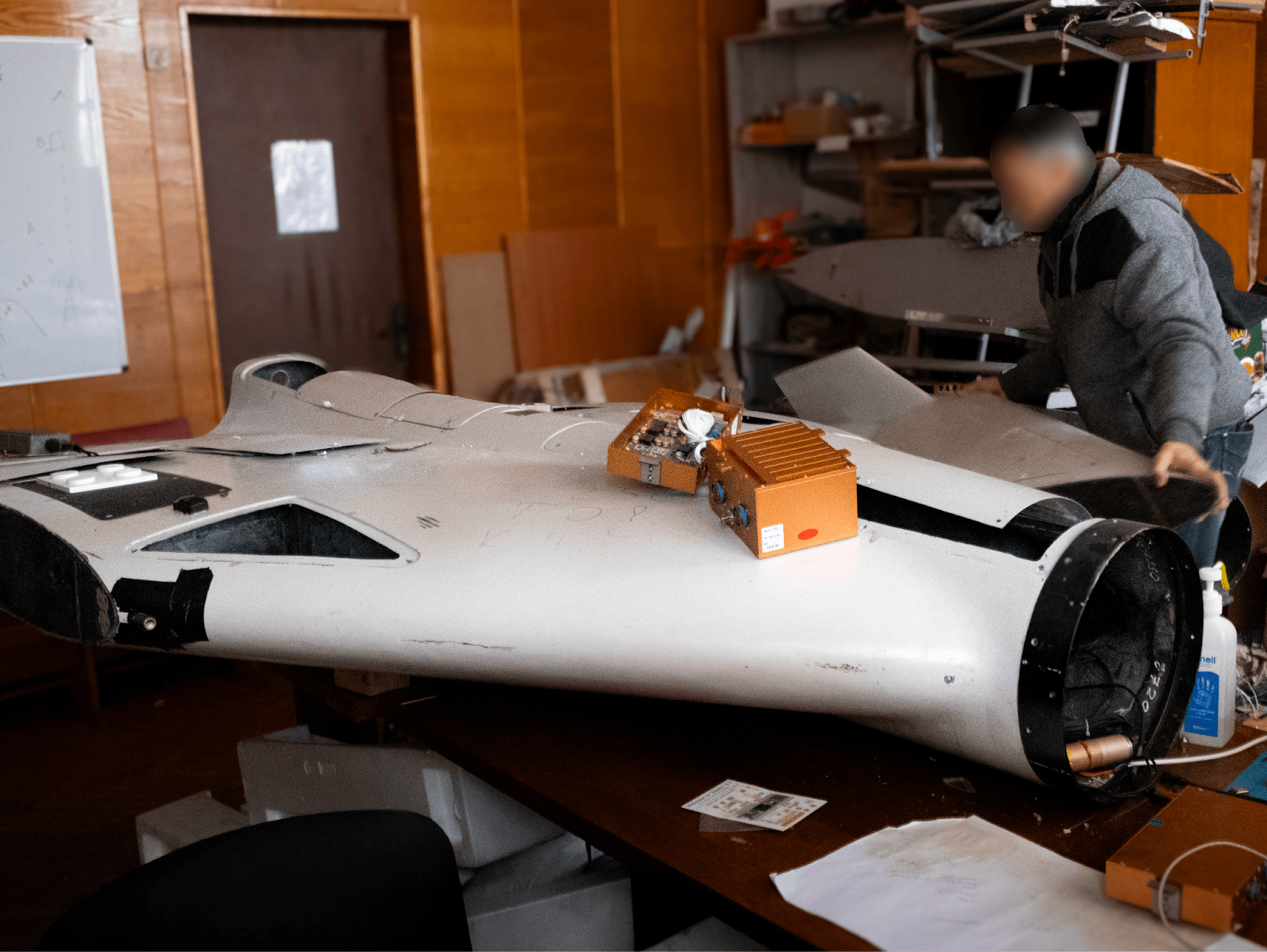

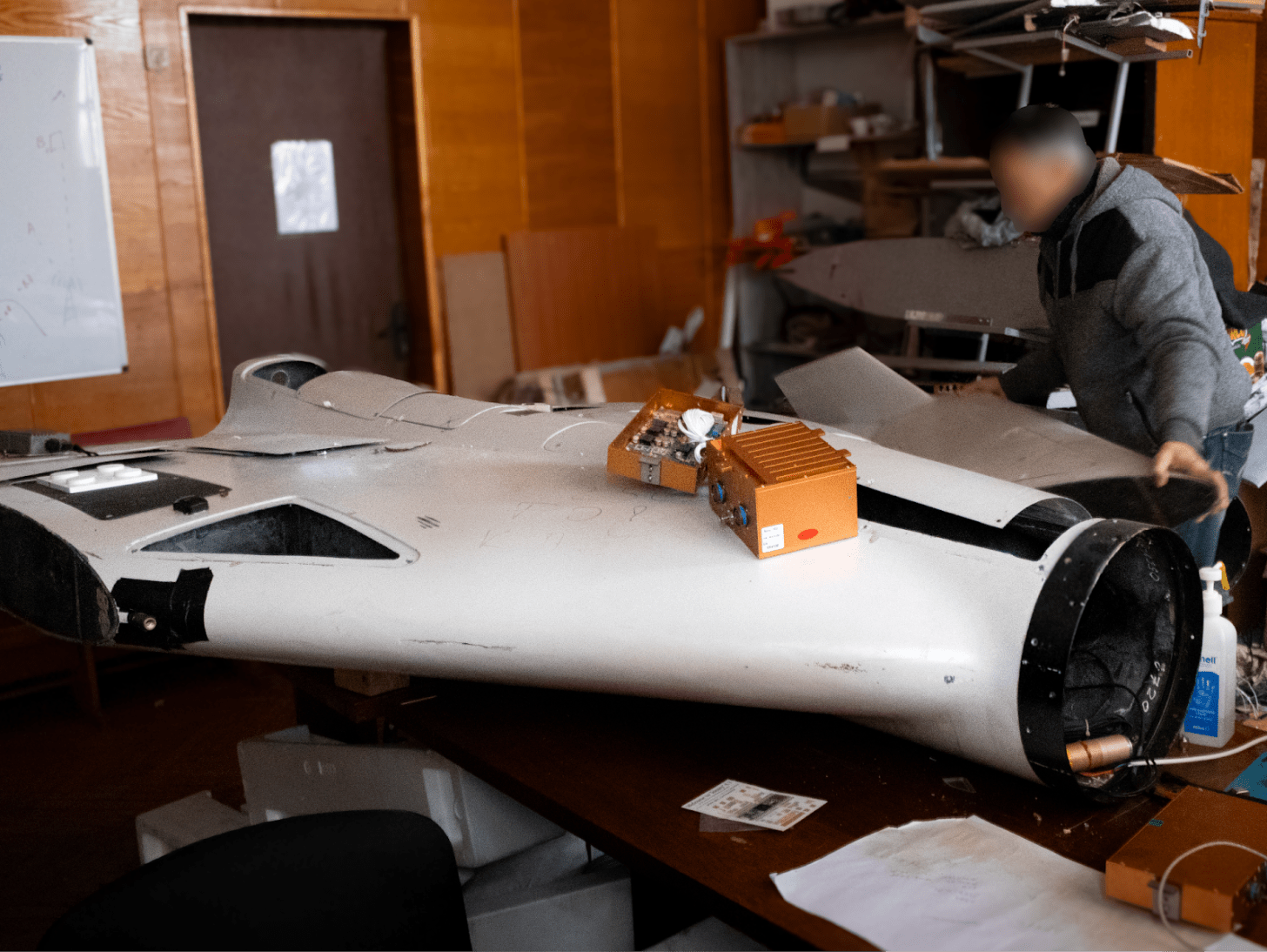

But it wasn’t a missile. Fiberglass was scattered around the pit, and farther away lay fragments of circuit boards and pieces of an engine.

He didn’t fully realize that over the next three years, he and his unit would see hundreds of similar craters. They were left by Shahed drones, which swarm over Ukrainian cities at night like vicious wasps.

A sound of Shahed drones flying over the city extracted from a TikTok video.

Since 2022, Russia has used around 60,000 Shahed drones in Ukraine, with almost 44,000 this year only. Reports like last week’s strike on Ukraine, when 600 Shaheds were launched, now barely register with people who live thousands of kilometers away from the war zone. While such news reports appear almost daily, there’s a personal tragedy behind every attack that often goes unnoticed.

Despite tremendous damage, Ukraine is dealing with the destruction from these strikes in record time, becoming an example not only for other countries at war but also for those dealing with other large-scale crises.

Serhii grew up in a village outside Kyiv, among warehouses filled with ammonium nitrate that were stockpiled there. Back then, according to Serhii, childhood was not spent “with phones.” Children went outside to play hide-and-seek or spent time near warehouses because there was little entertainment for kids in the villages. Already as a child, he knew how to make a small, homemade ‘explosive.’

“A bolt with some nuts, pour in match heads, and throw it,” said Serhii, now a bomb disposal technician.

Since many of Serhii’s relatives had tied their lives to the military, explosives were never going to remain just a childhood game. After serving in the Ukrainian police, he became a sapper after Russia’s initial invasion in 2014, before later returning to his regular duties in the Kyiv region.

Now he witnesses the chaotic aftermath of Shahed attacks firsthand, taking part in crucial efforts to document these strikes.

Russia began launching Shaheds over Ukraine in the fall of 2022, after Iran supplied them to Moscow. If earlier the word ‘drone’ brought to mind a small quadcopter used to film wedding videos, the Shaheds turned that notion on its head. These drones stretched more than 3.5 meters long and carried enough explosives to tear apart the side of a building, posing a threat on par with a missile.

When Shaheds hit the Kyiv region for the first time, nearly half of Serhii’s unit rushed to the scene.

They began with reconnaissance, which sometimes was as simple as using a phone with a powerful zoom to identify an object. Back then, Serhii’s team examined the crater with quadcopters while calling other services for guidance. At that moment, no one really knew what to do with a chunk of downed scrap metal.

But now, through experience, it has become almost routine.

As soon as darkness falls and the air raid siren begins to wail, the skies over Ukrainian cities light up with searchlights hunting for the drones that are already approaching. The buzz of Shahed engines is drowned out by air defense fire, which sounds like bursts from an automatic rifle.

Then a loud explosion —which means the Shahed has been shot down, or it has struck somewhere.

“Everything is calculated already at the planning stage... We work only within our assigned sectors and cannot shoot beyond them, especially in urban areas. We’d simply end up firing into someone’s windows,” an air-defense serviceman with the callsign ‘Kit’ ( ‘Cat’ in English) told The Counteroffensive.

Kit first notifies his command about the downing, then files a report, and together with his comrades calls the explosives unit to the place where the debris likely fell.

On the other end of the line, the rush begins: Technicians put on bomb disposal suits and head to the site in teams.

These days, Serhii can identify what kind of explosive a Shahed was packed with just by looking at the crater, as different warheads leave different-sized holes in the soil. Sometimes, by the sharp smell hanging in the air, even before he sees the drone’s debris.

“Lately, the Russians have been using warheads filled with incendiary mixtures [to trigger large fires at the crash site]. I can tell the difference between the smell of a TNT blast or an artillery shell. Incendiaries have a distinct burnt odor without getting close,” Serhii said.

When Serhii’s team arrives, a crowd is usually already gathering at the site of the strike or shoot down. Gas and electricity services check for gas leaks or short circuits. Medics treat the injured.

From time to time, you can hear crying and wailing if dead bodies are found at the scene.

Patrol police cordon off the area where the debris fell to prepare it for the arrival of the explosives unit. They must arrive quickly, although Serhii admits that when the entire region has only four teams, there are sometimes not enough hands during massive attacks.

The bomb technicians usually provide the initial assessment of the type of Shahed they’re dealing with. For example, there are cases when Russians launch decoys without explosives to exhaust Ukraine’s air defense. Such Shaheds are called ‘Geran.’

Investigators photograph the crash site, collect samples from the blast center, and send them for more precise analysis to document the latest war crime.

“Sometimes people from other services show up and shout, ‘Come on, hurry, hurry’… But we never rush. That can be a big mistake,” Serhii said.

For people who work with explosives, rushing leads to errors — and Serhii knows that all too well. “God saved” him three times at the front when he almost stepped on a tripwire. He couldn’t allow anything like that to happen to his team.

Explosive technicians, like snipers, always work in pairs. One works directly with the Shahed; the other monitors and provides cover, monitoring other threats, and help from a distance. Their main job is to destroy the warheads: if there are no buildings nearby, right on the spot; otherwise, they carefully and slowly transport them to improvised demolition sites.

The remaining debris is handed over for further investigation.

Each specialist mentally prepares to see both the injured and, likely, the dead. Lately, the sight of dead bodies has become the norm for them. Bomb technicians are often called to handle the exchange of bodies with the Russians, sometimes even those that are already decomposing.

“By the end of their shift, the guys are just collapsing from exhaustion. They can’t even fill out the paperwork because they fall asleep at the computer,” Serhii said.

In the morning, at briefings, everyone talks through what happened over the past day — all their fears and worries. Serhii’s team comforts and reassures one another, even when it’s about problems at home. Otherwise, the job won’t get done properly.

Meanwhile, investigators from the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) study the remnants of Shaheds and send them for examination.

One of the institutions that examines them is the State Scientific Research Institute for Testing and Certification of Weapons and Military Equipment, where the components of the Shaheds are analyzed. The results of these studies later become evidence in criminal cases against Russia and help impose sanctions on companies that assist the Kremlin’s war machine.

According to Colonel Oleksandr Zaruba, the chief research officer at one of the Institute’s departments, the Russians are constantly improving the Shaheds to inflict as much damage as possible. The drones are sometimes used to scatter mines or drop anti-Ukrainian propaganda over border areas, for instance.

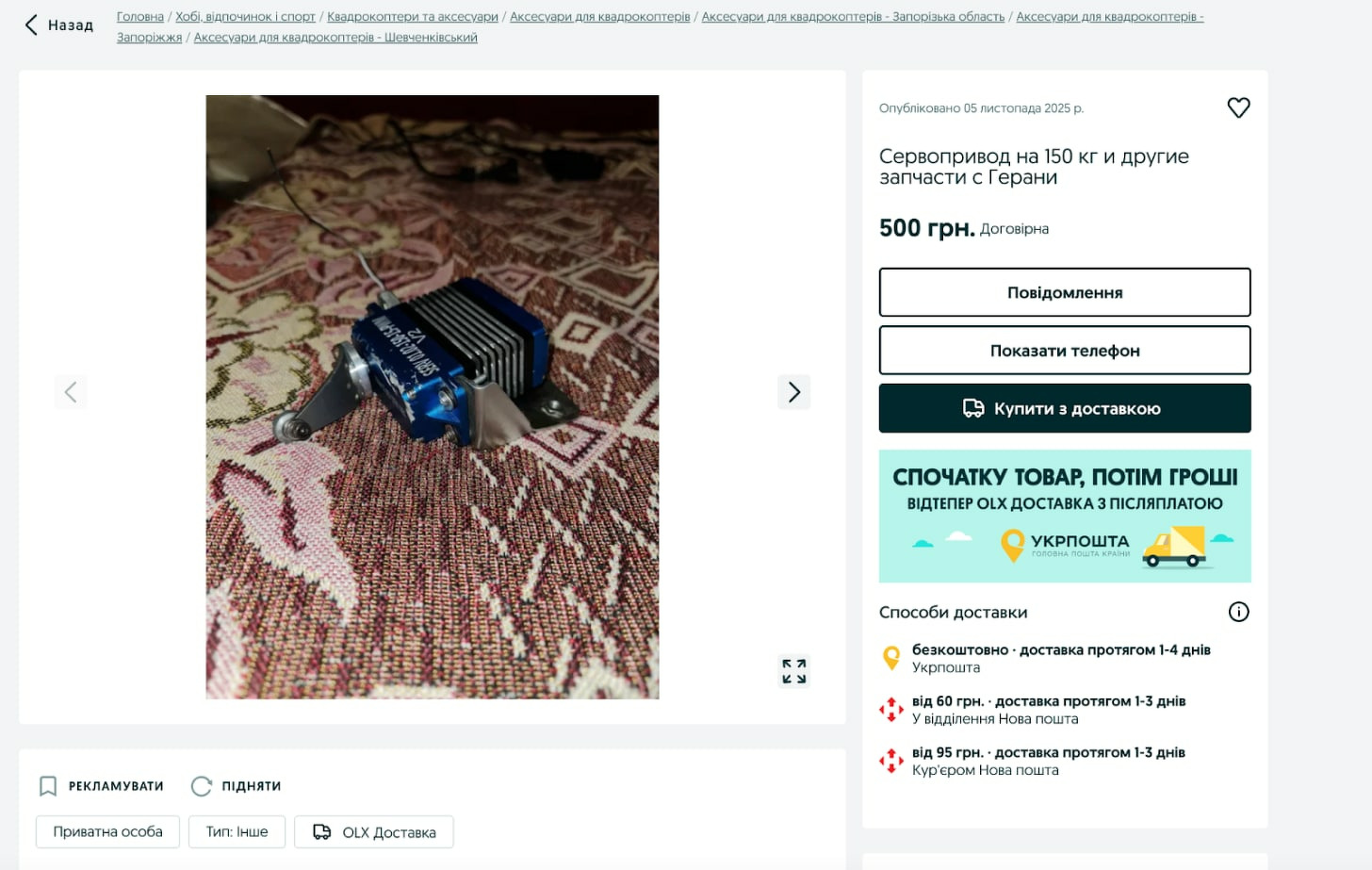

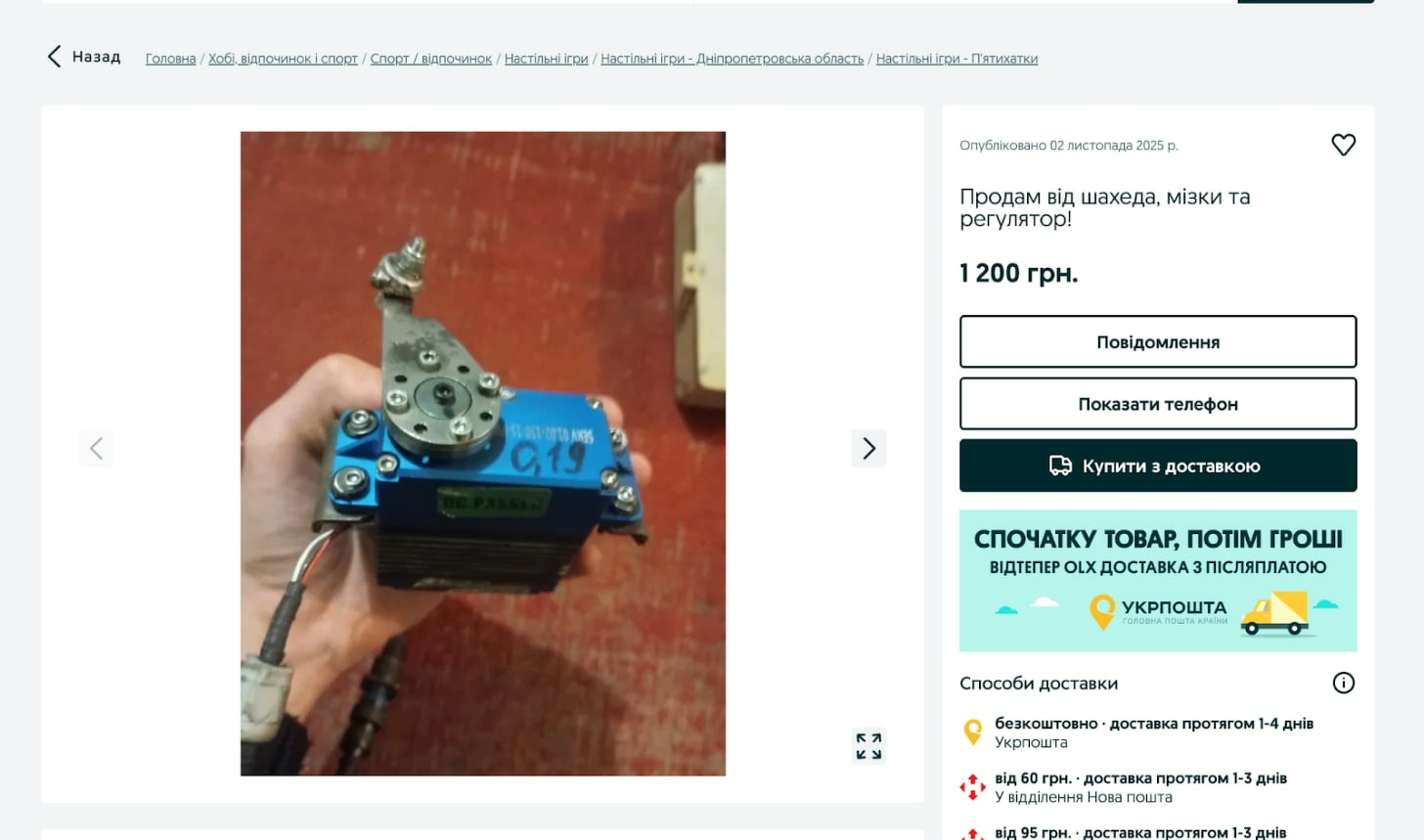

There are cases when Serhii’s team can’t reach the crash site in time, and the Shahed has already been taken by locals. This usually happens in villages further from Kyiv, where it takes an hour and a half to get there.

Serhii joked that Ukrainians “find a use for everything” around the house.

“We arrive at the crash site and there’s nothing left. Someone took the motor, someone took the batteries, someone liked some of the circuit boards and carried them off. And in the end they bring you only a piece of plastic [the empty drone shell],” Serhii said.

People mainly use motors from Shaheds or Gerans for agricultural purposes, such as building a small walk-behind tractor. There are cases where Ukrainians insist that if a drone landed in their yard, it is now their property and they can even sell it if they want. The fact that such antics can lead to administrative or even criminal charges doesn’t deter them, Serhii said.

After long, exhausting days on the road, Serhii can barely stay on his feet. He gets a chance to truly breathe freely only when he’s on leave, when he can finally devote himself to his family.

“When I come home in the evening, I try not to think about work. But during mass attacks, when they keep calling me, it’s really hard. I’m constantly stuck in this job,” Serhii sighed, taking a small pause before answering.

These calls aren’t always about attacks, though.

Sometimes bomb disposal technicians are called out, for instance, because a soldier has been drinking and is threatening to blow everything up with a grenade while his wife and children cry nearby.

Serhii’s own wife sometimes scolds him gently because, besides work, there are other things to take care of. After all, they have children, too.

But his work has already consumed him, and he can’t imagine himself outside of it.

A new day will begin, and he will have to head out to another crash site, figuring out how to disconnect the wires safely so that no one gets blown up.

“No one but us, the explosives technicians, can do our job.” Serhii said. “No one knows when it will end.”

*We are not disclosing Serhii’s full name for security purposes.

Correction: A previous version of this story included the incorrect audio for Shahed drone sounds. We apologize for the mistake.

Featured Subscriber’s Comment:

“I support this work because it the most accurate and valuable information and commentary about Ukraine. Authentic voices of surving journalists who work with Tim Mak. And the incredible DNA of fighting for democracy for ALL OF US shines through. Thank you Tim Mak for all you do.”

By: Elizabeth K. Baker

NEWS OF THE DAY:

By: Tania Novakivska

ABDUCTED UKRAINIAN CHILDREN SENT TO NORTH KOREA CAMPS: Kateryna Rashevska, an expert at the Regional Human Rights Center, noted that at least 165 camps have been set up, not only in Russia, but also in Belarus and North Korea.

The Kremlin has said that the deportation of Ukrainian children is an evacuation, but has failed to provide lists of the deported children to the Red Cross and has not explained the reasons for their detention.

JOINT UK-NORWAY FLEET TO COUNTER RUSSIAN THREAT: In the North Atlantic, the UK and Norway will now operate a joint fleet, consisting of British-built Type 26 frigates, to counter underwater threats from Russia.

This is due to a 30% increase in the number of Russian vessels, which threaten the waters of the United Kingdom over the past two years.

MERZ ARGUES FOR EU RISK SHARING IN USING RUSSIAN ASSETS: German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said that each EU country should bear an equal share of the risk in using frozen Russian assets for Ukraine.

This comes as Belgium, home to Euroclear which holds most of the frozen Russian assets, pushes back against the move. The Belgian Prime Minister has called it “fundamentally wrong” to use the frozen assets.

DOGS OF WAR:

Tania’s dogs, woken up by the smell of food, stared on Tania on a peaceful Sunday evening.

Stay safe out there!

Best,

Mariana