Editor’s Note:

You may have noticed that 60 Minutes recently held up a report on this El Salvadorian prison, CECOT.

We decided to double down on our independent journalism and push out this story so you could get a sense of the conditions there.

Support independent journalism? Upgrade today to get access to all our stories.

Warning: This article contains details that may be disturbing for some readers.

Nestled near the mountains, far from any settlement, stands a prison ostensibly made for the most dangerous terrorists and criminals.

Some consider the El Salvadorian institution one of the strictest prisons in the world.

“Welcome to hell,” said the prison director to over 200 newcomers. “You will leave it only dead.”

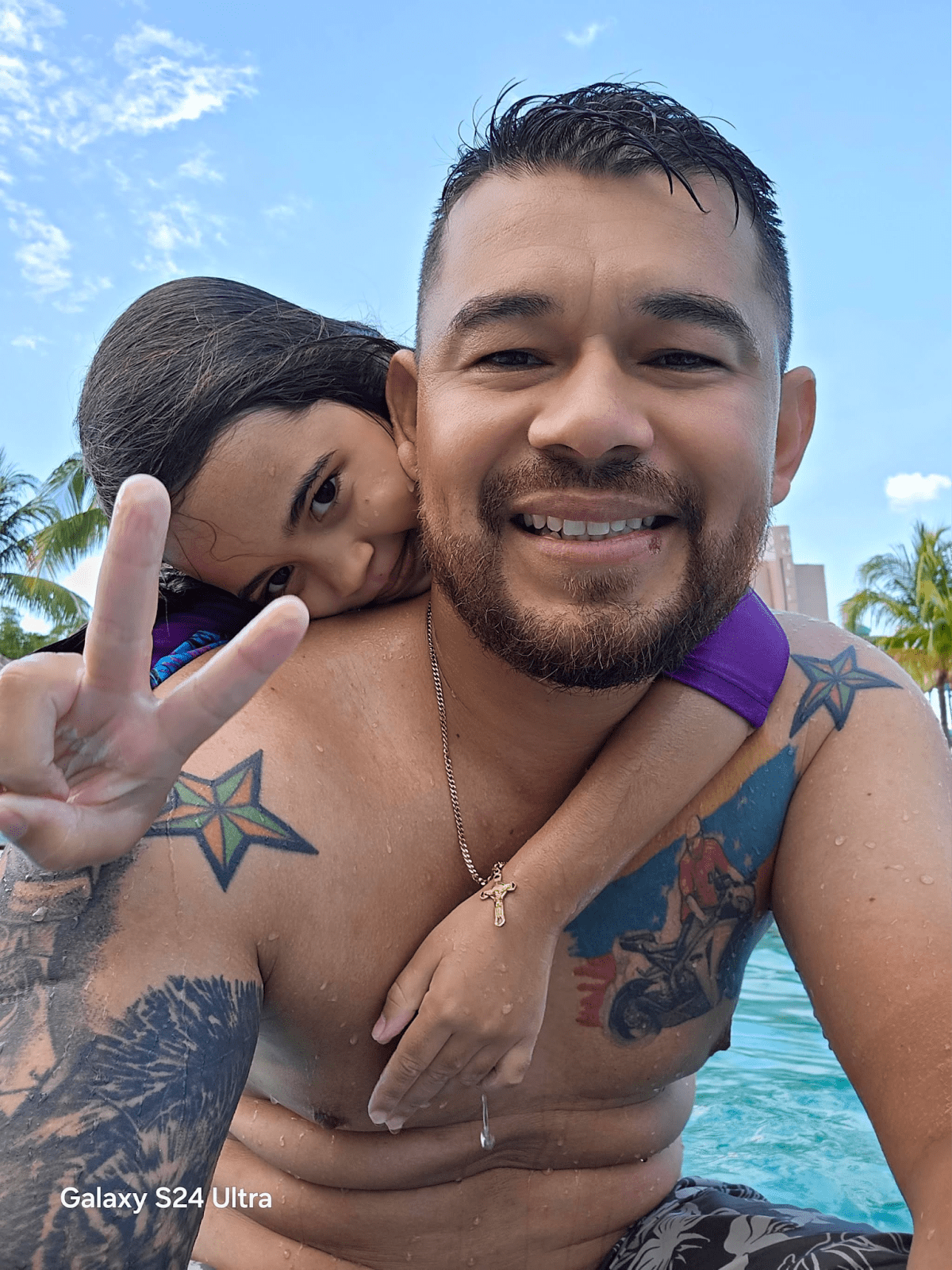

Andry Omar Blanco Bonilla, from Valencia, Venezuela, had seen videos about this place on YouTube.

Now, he asked himself: what has gone wrong in his life for him to end up here?

Andry was among 252 Venezuelans who were sent by Trump’s order to the maximum-security prison in El Salvador, known as the Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, or CECOT.

They were accused of being members of the Venezuelan criminal gang Tren de Aragua, though no one provided any evidence. People with no criminal record, who were fleeing poverty, ended up confined in inhumane conditions alongside 40,000 dangerous criminals.

At the prison, they were tortured and abused, including sexually, according to Human Rights Watch. One detainee was allegedly forced to have oral sex with one of the prison’s guards, while the others were called homophobic slurs.

The event formed the basis for hostile ties between the U.S and Venezuela, which culminated Saturday with the American bombing of Caracas.

It was a sign that Trump’s ambitions are to enforce a ‘might-makes-right’ philosophy in the Western hemisphere – where migration itself is treated as a crime and a military intervention to any country is justified.

For Andry, making ends meet in Venezuela was almost impossible.

Still, his growing up there had some brightness. His youth was filled with the loud sounds of motorcycle engines. It was a passion that led to him meeting his partner, Susana, at a motorcycle exhibition.

“We dated for a couple of months, getting to know each other. Over the years, our feelings grew stronger. What caught my attention most about her? Her gaze, her smile, her laugh,” Andry said.

Just 20 years ago, Venezuela was a promising country because it held the world’s largest proven oil reserves. Today, it is associated with economic crises, hyperinflation, repression, and a humanitarian catastrophe. The situation worsened after the political crisis in 2019, when Nicolás Maduro usurped power following rigged elections.

So Andry found himself at the U.S. border at the end of 2023. He did not have a work permit, so he immediately surrendered to border authorities and filed for asylum, hoping to be able to work in the U.S. legally.

After a month, Andry visited the immigration center to update his address. Fortune was not on his side.

“Do you have any tattoos on your body that are not visible?” the officer asked while processing his address change.

“Yes,” Andry replied as his chest, back, and leg were partially covered with ink. He explained the personal meaning of each. The drawing of a clock showed the time of his mother’s birth.

The officer was unsatisfied.

“The officer practically wanted to force me to affirm something that was totally a lie, to say I belonged to a gang,” Andry recalled. “He just said, ‘You’re detained.’”

Among Venezuelans, tattoos have sometimes been associated with the transnational criminal organization Tren de Aragua, which is involved in drug, weapons, and human trafficking.

The supposed fight against this organization became a focus of Trump’s second term. In February, the Trump administration designated Tren de Aragua as a foreign terrorist organization. From that point on, the United States attacked Venezuelan infrastructure and conducted military operations – culminating in Saturday’s capture of Maduro.

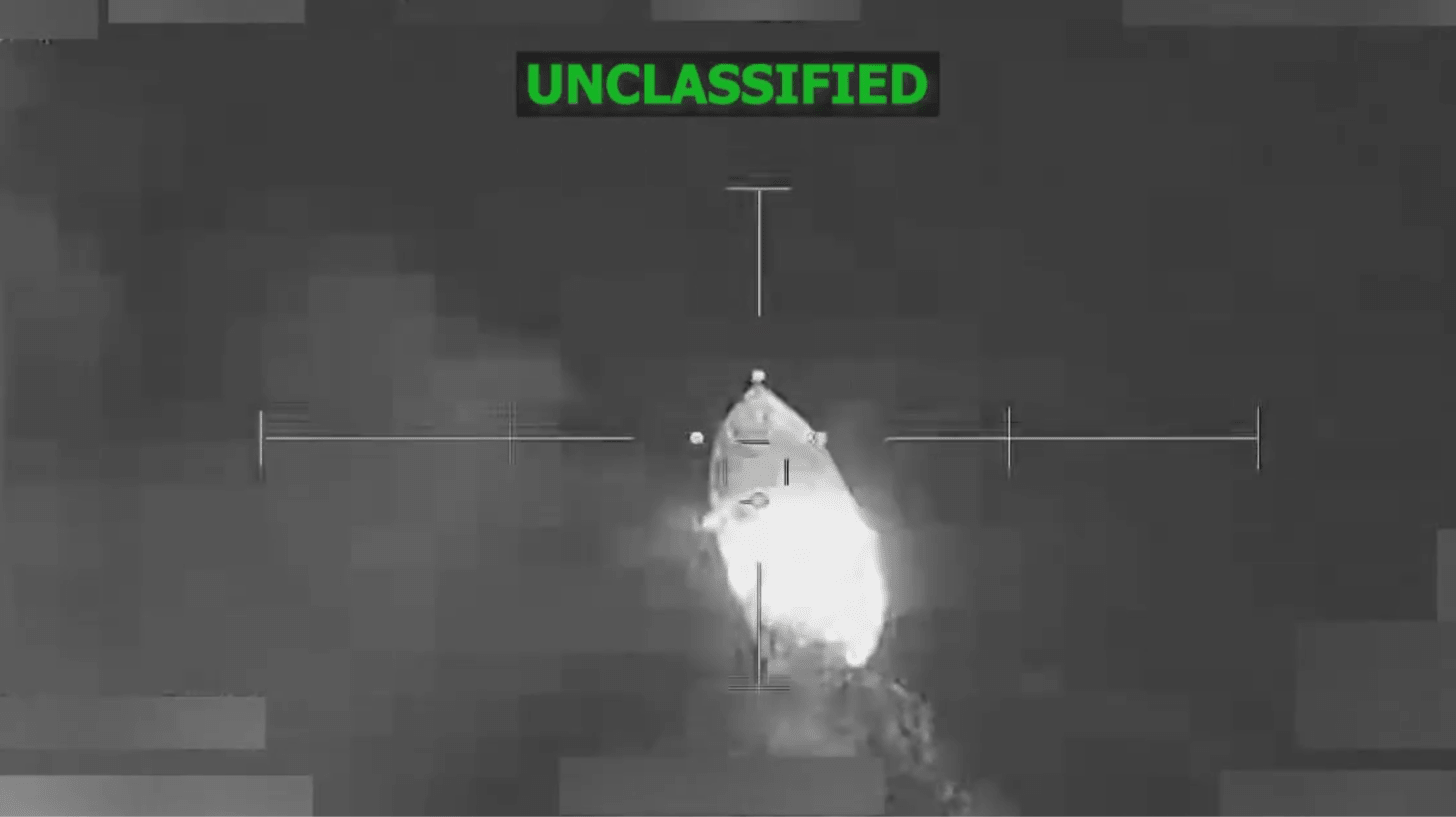

More than one hundred Venezuelans have already been killed in boat strikes, even though the Trump administration has so far failed to provide evidence that these boats belonged to cartels or were carrying drugs.

A similar thing can be said of Andry: there was no evidence of his involvement in a criminal gang — other than the government’s interpretation of his tattoos.

The U.S. detained Andry for five months, labeling him as a “danger to society.”

“I’ve been a person with an impeccable record. I’ve never been detained, never been imprisoned, never had a legal problem in the U.S., not even a traffic ticket the whole time I was there,” he said.

Venezuela and the United States have severed diplomatic relations. When it became clear that deportation directly to his home country was impossible, the court released him on bail for several months.

Andry bought himself a plane ticket to return home to Venezuela in April 2025. He did not want to wait for ICE to come and deport him. But in February 2025, they acted first.

He was told to appear at an ICE office the next day to update his data. It was a ruse. When he showed up, he was detained. They put handcuffs on Andry, “violently, like a criminal,” he recalled.

When Andry said that he already had a ticket to Venezuela and could exchange it to the nearest date, the officer responded: “You should have left when you could.”

What followed was a nightmare most of us can barely imagine. After another month of detention with no clarity on his future, he thought he was returning home.

Andry boarded a military plane and was told not to raise the window shades.

When the plane landed, instead of being back home in Venezuela, he saw the El Salvador flag. He was pulled off a bus in front of a massive fortress-like building surrounded by electric fences and dozens of watchtowers.

Trump had sent him, along with other Venezuelans, to El Salvador by invoking an 18th-century military law that allowed the deportation of people without judicial review.

“They told that we were ‘welcome’ to the CECOT, what they now call the concrete hell,” recalled Andry.

The only option was to resign himself to a suffocating cell, a bed without a mattress, and white prison clothing. He had no way to contact either his family or a lawyer. There were days that he did not know if there would be a tomorrow, due to severe hypertension and a lack of adequate medical care.

“I was being beaten, treated verbally and physically very badly. I questioned myself a lot about why I was there,” Andry said.

Inside the cells, detainees had no access to proper hygiene: each cell had only two sinks and two toilets, without any partitions. The lights in the cell were not turned off at night. The food was always the same and had to be eaten by hand.

According to Human Rights Watch, the guards took the detainees from the cells every day to search them. The deportees were forced to kneel and were beaten with kicks and fists, as well as batons.

There were ten people in their tiny cell, which was designed for 80. They were already losing their minds, but perversely prison staff told them to be grateful. Other cells like theirs held 150–200 people, they’d say.

From his first day in El Salvador, Andry felt like he had been kidnapped. Deprived of any human rights, he was trapped in a cell as if he were a dangerous criminal. However, the most difficult for him was not knowing what was happening to his family, if they even were aware he was detained in a prison for terrorists. He tried to support himself day by day by talking to his companions in the cell and recalling warm-hearted moments about his youth and family.

At CECOT, prisoners are not allowed to do any activities outside of their cells besides half an hour of physical exercise in handcuffs. During the remaining 23 and a half hours, they are left with only two Bibles per cell. That was the only thing that saved Andry, who had felt distant from God until he found himself in hell.

“All our time there passed in uncertainty, not knowing when we would have the opportunity to see light again. We were detained inside the cell every single day. They never took us out to get sun or fresh air,” Andry recalled.

His freedom was to come unexpectedly in the early morning hours of July 18, 2025, at approximately 1:30 a.m.

Andry was already sleeping because of his curfew, which required him to be in bed by 9 p.m. each night. The prison director entered, together with other officers, who were banging on the cell bars and saying to get up, bathe, and dress.

“You’re returning to your country, your hell is over,” Andry heard from the CECOT director.

They were traded for Venezuelan political prisoners and ten American detainees who were held in the country. Andry reunited with his family in Venezuela, and is now back home in Valencia.

But his arrival in Venezuela now coincides with the next stage of escalation, when the U.S. has attacked his country directly.

“There’s a bit of fear about what could happen. There’s no war or intervention where there hasn’t been some loss of human life,” he said.

At least 40 people died, including civilians, as a result of yesterday’s American attack on Caracas, the capital of Venezuela. Besides striking military infrastructure the U.S. also hit a three-story residential complex in a coastal area of the city.

Andry is currently safe with his family, but a period of political instability looms. The United States – the country which sent him to a prison hell – is now claiming that they will “run” Venezuela for the foreseeable future.

Competing claims for power in Venezuela could lead to civil war, prolonged conflict, or an even worse situation than he was trying to escape years ago.

«[The war is not] what I.. want for my country either. It would destabilize the country much more than it’s already destabilized today,” he said.

Abby Pender contributed to this reporting.

Editor’s Note:

You may have noticed that 60 Minutes recently held up a report on this El Salvadorian prison, CECOT.

We decided to double down on our independent journalism and push out this story so you could get a sense of the conditions there.

Support independent journalism? Upgrade today to get access to all our stories.

NEWS OF THE DAY:

By Oksana Stepura

Good morning to readers; Kyiv remains in Ukrainian hands.

NUMBER OF WOMEN IN ARMY SURGES: The share of female officers in the Ukrainian army has jumped from 4% to 21% over the past 2 years, Oksana Hryhorieva, the Ukrainian army’s gender adviser, told Hromadske Radio.

While women in the army have become captains and majors, due to a lack of training no woman in the army has risen to the rank of combat general.

NO STRIKE RESTRICTIONS, NO NEW WEAPONS: Following a meeting with foreign security advisers, Zelenskyy said that allies are no longer imposing restrictions on strikes inside Russia, but are instead withholding certain types of weapons from Ukraine to prevent these strikes.

Zelenskyy noted that Ukraine is currently in a phase of “use what we have”, while the equipment that partners don’t want to be used by Ukraine isn’t being delivered.

U.S. VENEZUELA ATTACK CASUALTY COUNT: At least 40 people were killed in the U.S. attack on Venezuela, according to New York Times, citing a Venezuela official. There were no U.S. casualties but about six American troops were injured during the operation which captured Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro.

The NYT’s sources in the U.S. government said that Maduro rejected an American proposal that would have allowed him to flee to Turkey. This was allegedly offered as a counter-proposal after Maduro offered the U.S. access to his country’s oil, in an attempt to prevent an American raid.

VENZUELA’S DIRTY, EXPENSIVE OIL: The infrastructure needed for peak oil production in Venezuela would cost $100 billion and take about ten years, The Washington Post reported. The challenge comes with ensuring sufficient security and stability to make such long term investments worthwhile and profitable.

The oil in the country is also a form of heavy crude which is more difficult to process and refining the oil requires more carbon emissions than other types of oil. There are also concerns about the resilience of Venezuela’s energy grid, as oil production is extremely energy-intensive.

CAT OF CONFLICT:

Oksana’s Mary is very curious about a mouse she spotted.

Stay safe out there.

Best,

Mariana