Editor’s Note:

The Counteroffensive brings you human-first reporting from Kyiv to Caracas.

This isn’t easy – support this initiative: to bring you closer to the places where the fight for democracy is underway.

Upgrade now to support our work and get full access to all our writing.

CARACAS, Venezuela – José Bodas says you could blindfold him, place him anywhere inside the Puerto La Cruz oil refinery, and he’d know exactly where he was.

The sensation of the winds, the rhythmic percussion of the machinery, the sounds of valves and compression pumps, and the pungent smells – he can segregate them all and associate them with a specific section.

He was in 11th grade when he first started working at Puerto La Cruz refinery in Anzoátegui, Venezuela. At that age, José was fascinated by cars and the way gasoline could power almost anything. He earned a technical diploma in petrochemical operations upon graduating high school and began working at Puerto La Cruz in 1987, when he was 18.

“I found it extremely interesting because it was something totally different,” said José. “I was thrilled to acquire a great amount of knowledge, and it was going to give me an opportunity to develop professionally in the main industry of the country.”

Almost four decades later, José still works at the refinery as a plant operator. He is also the secretary of Venezuela’s Unitary Federation of Petroleum and Gas Workers, the largest labor union in the Venezuelan oil industry.

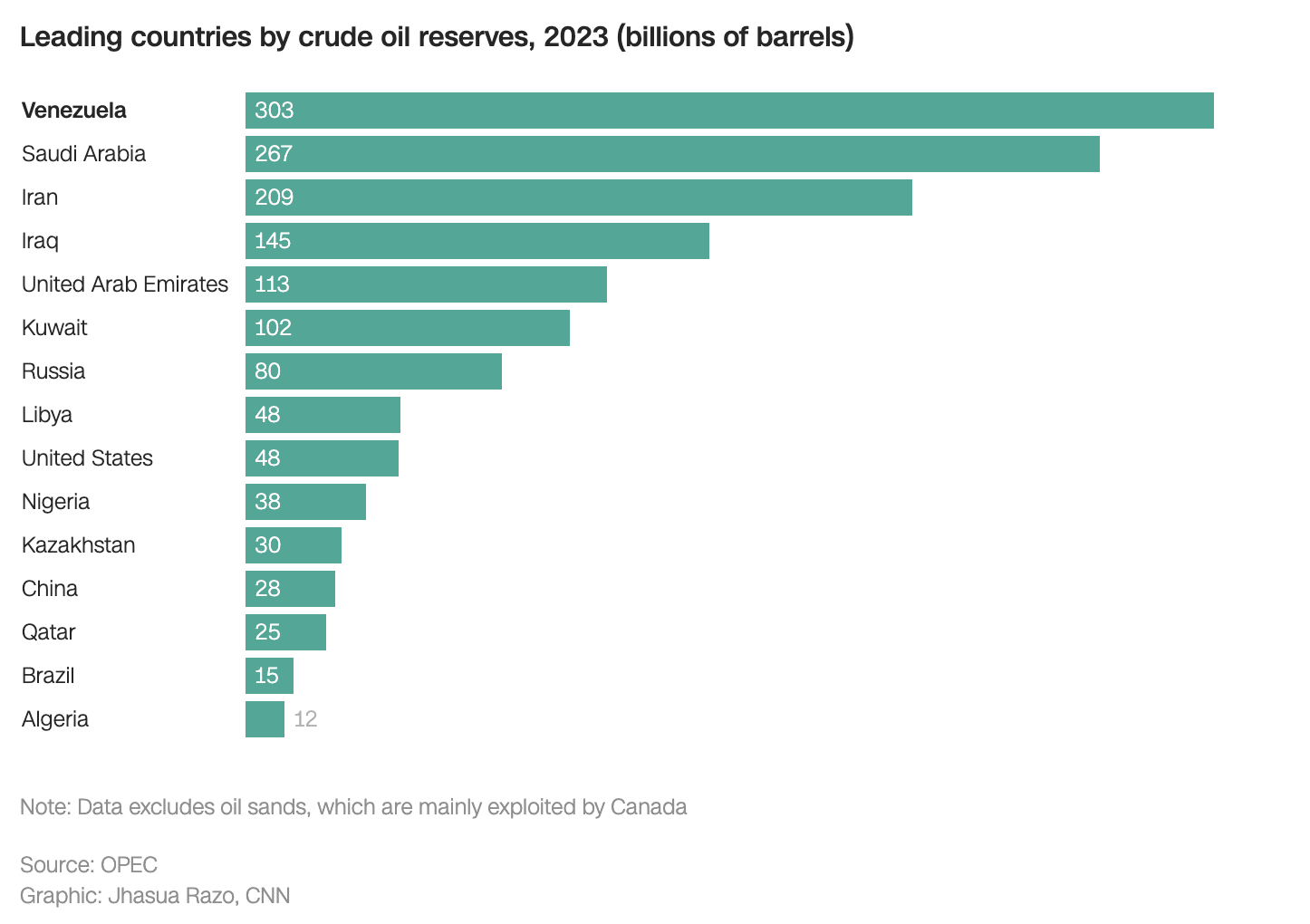

Workers like José have kept Venezuela’s oil industry alive, an industry based on what makes up about a fifth of the world’s crude oil reserves. In return, they are often forced into an uneasy balance, caught between the threat of repression by the regime, the moral obligation to speak up for workers’ rights, and pressure to sustain the oil necessary for the world to run.

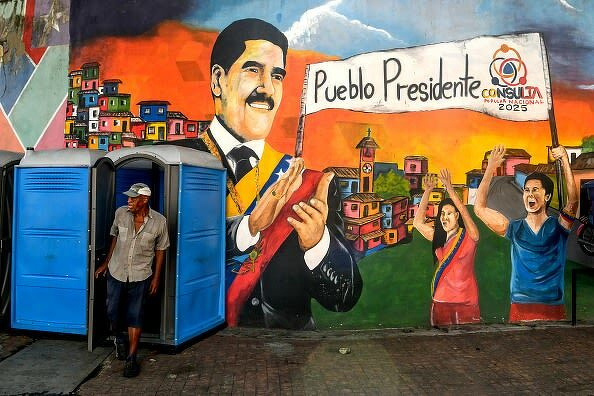

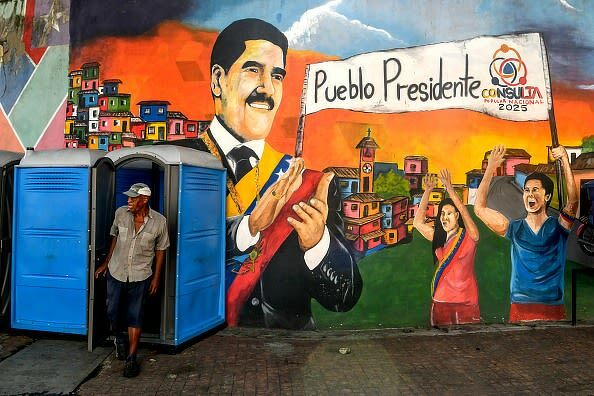

The Trump administration’s strike on the capital, and subsequent capture of President Nicolás Maduro, was an escalation of the campaign in the Caribbean.

Trump framed the offshore strikes and rising tensions as a fight against drug trafficking and criminal networks. But he has since claimed the right to seize oil – and its revenues – from the Venezuelan government.

Venezuela’s oil sector was once the backbone of its economy, but it has plummeted under decades of authoritarian rule. Since 2013, when Maduro took over for Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s oil output has dropped from 2.8 million barrels per day to 800,000, according to Axios.

There are major geopolitical implications, including for Ukraine. Russia’s close ties to Venezuela – and its dependence on oil revenues to fund its war effort – means that Russia will suffer from the latest changes.

The U.S. has seized at least five oil tankers from the region, one of which was Russian-flagged, since the beginning of December. Last year, most Venezuelan crude oil went to China, while Cuba, Iran and Russia all received imports, too.

Meanwhile, inside Puerto La Cruz, the work never stopped.

“We have three work shifts at the refinery: the early shift from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m., the second one from 1 p.m. to 11 p.m., and the night shift from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m., or more if there was no one to replace us or an emergency,” said José.

They were constantly repairing pumps and compressors, preempting problems before they boiled over.

“What was our goal? To prevent emergencies and disasters. That is in our DNA: to protect the refineries. Because if you protect the refinery, you protect lives and the environment,” he explained.

Despite long hours and less-than-ideal working conditions, José loves his job:

“Many say that this privilege belongs to athletes, scientists and artists, who work in a job that pleases them. But it’s essential for every human being to have a job that pleases them. That’s part of freedom.”

José had long identified with the political left. He recalls being 18 when he saw armed forces massacre Venezuelan citizens during protests.

“I didn’t learn that in books,” he said. He lived it. He voted for Chávez hoping for change:

“We wanted to dance salsa, we wanted to change organized life. But we were not experiencing a deep crisis”.

But when Chávez ordered a mass purge of oil workers, José knew that bad times were ahead. The regime was replacing managers not according to merit, but according to allegiance to the ruling movement, known as chavismo.

Over the course of his early career, José witnessed first-hand the strict refinery rules that led some of his co-workers to utter exhaustion.

Overtime, if requested of a worker, was absolutely mandatory.

“One colleague had a son’s birthday,” José recalled. “Their family is waiting for them at home with a cake. But he couldn’t leave the refinery. That kind of exception doesn’t exist.”

It’s a hard job, he said, but it pays well – at least for the region.

The minimum wage in Venezuela is 130 bolivars (less than $0.40 American dollars) per month. There are other governmental bonuses that can increase that monthly payment anywhere between $100 and 400 USD.

During his young-minded observations of injustices in the refineries, he felt compelled to start studying law at Santa María University in his country. By his late 20s, he had joined the union.

“My ultimate goal is to defend Venezuelans workers’ rights, no matter their ideology, their religion… because we are human beings first and foremost”, he said.

In 2002, management told him to wear red on Fridays in celebration of the Bolivarian Revolution, he remembers. The Bolivarian Revolution is an ongoing movement that was started by President Hugo Chávez and named after Simón Bolívar, a leader of Latin America’s independence movement. It promotes nationalism and a state-led economy, often associated with working-class politics.

José refused. He wore white. Sometimes, managers denied him entry to the refinery when he wore anything but red.

Threats to civil rights freedoms have only worsened since then, said José. He witnessed colleagues detained for protesting and watched the military try to dismantle large gatherings of oil workers.

On February 3, 2014, José and 10 other union leaders were arrested in Puerto La Cruz. They were protesting for labor rights and fair wages. Venezuela was going through a state of hyperinflation, and the minimum wage was less than 10 dollars a month.

José spent three days in prison. For months, he was under probation and had to visit the court periodically to prove to the regime that he and his colleagues hadn’t left the country.

“To denounce a regime carries a lot of risk, but my responsibility to the people, with the oil workers’ rights, motivates me to continue,” he said. “There is a great responsibility to all Venezuelans.”

Today, according to José and other oil workers at Amuay and Cardón refineries who will remain anonymous for safety purposes, the Venezuelan military monitors workers’ phones at the start and the end of their shifts to hunt for any criticism of the regime.

Union leaders are routinely charged with “terrorism,” he said. As of January 2026, José and his colleagues at the union are tracking more than 100 cases involving detained energy sector workers in Venezuela.

Ivan Freites was once a former union leader in Venezuela ‘s oil industry. But he fled to Miami amid political repression – he relates to the hard hours, the intolerance for political dissent, and hopes that Maduro’s capture will be a positive moment for the country.

“One of the most important days for us was seeing Nicolás Maduro being handcuffed,” said Ivan. “Venezuelans tried everything to have a transition, but his regime was relentless… I thought his regime would not end.”

There is a real drive, said Ivan, to revive the success of the Venezuelan oil industry.

Friends of his who moved away, some to Saudi Arabia, to work in oil in a place with a better quality of life, say they still want to come back to Venezuela and be part of this revival movement, even if it means living on 130 Bolivar a month.

José’s attitude continues to be hopeful, too.

“We, at the Puerto La Cruz refinery, have a motto: Through challenge, the working class will have rights,” said José.

He hopes that oil workers have a say in the future of Venezuela and, hopefully, in a democratic transition of power. Where every worker can earn a livable wage, speak freely, organize without fear, and choose how Venezuelan oil benefits its own people.

“I will try to stay on the same path to defend working class rights”, he repeats again and again. “I stand with the liberation of all political prisoners in Venezuela”.

Editor’s Note:

The Counteroffensive brings you human-first reporting from Kyiv to Caracas.

This isn’t easy – support this initiative: to bring you closer to the places where the fight for democracy is underway.

Upgrade now to support our work and get full access to all our writing.

NEWS OF THE DAY:

By Oksana Stepura

Good morning to readers; Kyiv remains in Ukrainian hands.

MI6 CHIEF WARNS ABOUT RUSSIAN SABOTAGE: The UK’s new MI6 Chief warned about Russia’s strategy to destabilize the West in her first public appearance since taking on the position.

She emphasized that Russia will resort to using non-state actors, including petty criminals recruited online to individuals and shell companies who operate via legitimate-looking businesses. These agents are often paid by Russia via untraceable cryptocurrency to conduct deniable sabotage and economic warfare on behalf of the Russian state.

U.S. URGES CITIZENS TO LEAVE VENEZUELA: The State Department has urged all Americans to leave Venezuela immediately due to extreme security risks.

Armed pro-regime militias, known as ‘colectivos’, are reportedly setting up roadblocks to search vehicles for U.S. citizens or supporters.

POTENTIAL NATO DEPLOYMENT TO GREENLAND: European allies are discussing the possibility of sending NATO troops to Greenland to bolster Arctic security amid fears that Trump may illegally seize the territory.

The plan aims to counter Russian and Chinese influence in the region while persuading Donald Trump to abandon plans to annex Greenland.

CAT OF CONFLICT:

Oksana’s Mary loves Christmas trees.

Stay safe out there.

Best,

Jacqueline