Featured subscriber note from reader Tai:

“Praying for you, Myroslava and Nastia, as well as the rest of the team. Folks who are able should keeping feeding the tip jar and find ways to donate to various organizations purchasing batteries for Ukrainians. Slava Ukraini.”

Amir Rashidi was arrested in Tehran on New Year’s Day in 2009, swept into a security van with fourteen others.

Inside, other detainees scrambled to call friends, asking them to scrub their names from any public writing, anything that might be considered criminal to the regime.

Amir did not make that call. When asked why, he answered without thinking.

“I’m an internet guy,” he said.

At the time, he insists, it wasn’t bravery. It was instinct, shaped by years of moving between activist circles and writing code, by an understanding of how information traveled and how quickly it could disappear.

Today, Amir is the Director of Cybersecurity and Digital Rights at Miaan Group, an Iran-focused human rights organization centered on digital security and activism.

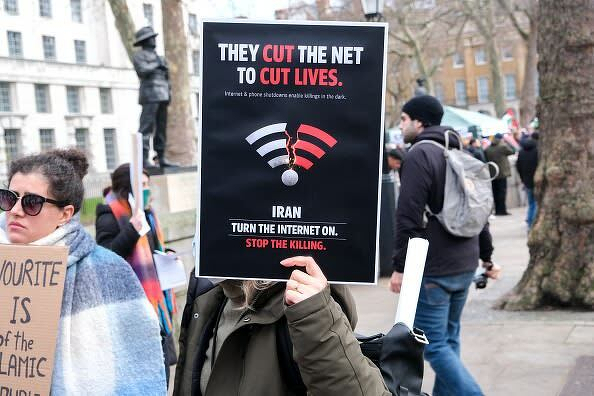

As protests swept Iran starting in late December and rights groups tallied the death toll, Iranians watched their internet abruptly disappear.

That plunge into digital darkness, Amir warns, is not just an Iranian issue. It reflects a more global shift in how authoritarian governments are learning to control information quietly.

It would be a mistake to watch Iran fall offline without asking how it happens – and how we all might be vulnerable to the same blockades.

Amir was born in Tehran to an educated family — his father was a teacher, which he would later pick up. He studied software engineering and computer science at a private university in Iran, training for a career as a developer at a precarious moment for technology in Iran; it was brand new, but already shaped by restrictions.

Amir has also always been an activist. As a student, he worked with student rights activists and later became active in the women’s rights movement, including by signing the One Million Signatures campaign against discriminatory laws against women. He was a familiar presence at protests, documenting what he saw and sharing information as it unfolded.

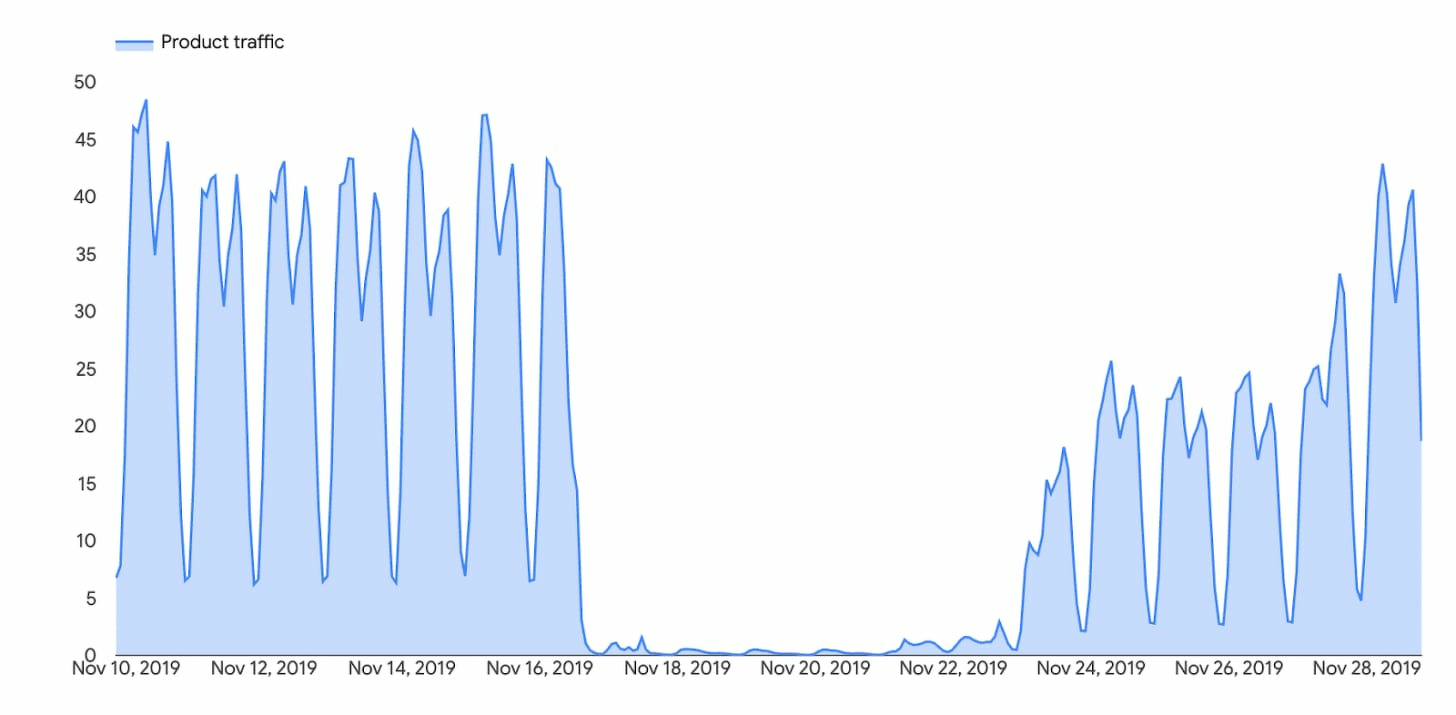

Amir cites November 2019, when more than 1,000 protesters were reportedly killed during a wave of unrest regarding fuel prices, as the first real internet shutdown in Iran.

After that, he said, the regime created a very clear chain of command: To shut down connectivity in a town or city, approval must come from the minister of interior. A nationwide shutdown requires authorization from the president.

So, what really is an “internet blackout?” A severed underground cable? A single red button?

“There is no kill switch,” Amir said. Instead, control is exercised through infrastructure.

Iran has only two internet “gateways,” or connection points to internet traffic — far fewer than most countries.

In practice, nearly all internet traffic entering or leaving the country passes through a state-controlled body, the Telecommunications Infrastructure Company. Much of that control is carried out by two private companies, Yaftar and Douran, said Amir, making it easy to cut most of the country’s access when those two companies shut down clients’ access.

This control can sometimes feel unbeatable.

“We are so alone,” said Amir, “and we are fighting against a regime with all the resources.”

Iran has shut down or severely restricted internet access at least twelve times, said Amir. In 2019 during nationwide protests, the Iranian government cut off the global internet, erasing it from the rest of the world network by network.

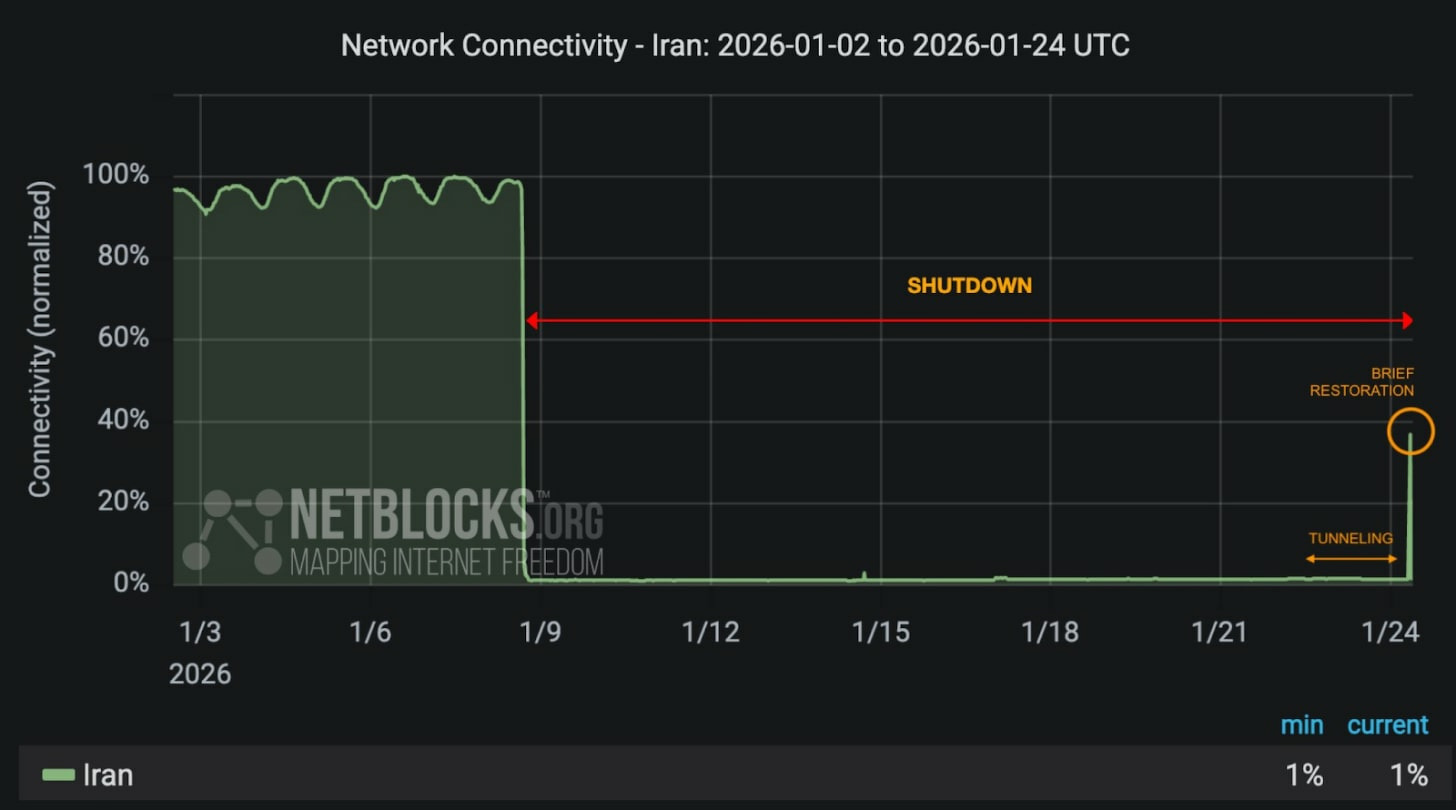

During the recent 2025 conflict between Iran and Israel, authorities imposed what Amir described as “the most severe internet shutdown we have ever had.” A report from Miaan Group found that while Iran’s 2019 shutdown lasted six days, the blackouts that followed the killing of Mahsa Amini in 2022 and the 2025 conflict stretched on for nearly two weeks.

The current disruptions are ongoing, and have already surpassed the two week mark.

What it looks like for Iranians, beyond the technical aspects, is quite simple.

Messages don’t send. Calls fail. Searches don’t load.

“I think they don’t realize how close this might be to them, because Iran is exporting this technology,” said Amir. He said that Miaan Group has evidence that Douran, one of the two main contractors in Iran, is exporting their technology to Russia and certain African countries.

Internet access is an emerging tool for authoritarian regimes to remain in power, unchallenged.

Access Now, a group that follows and advocates for digital rights globally, tracked internet shutdowns in 2024, when at least 64 countries were expected to hold national elections. After all, political events, like elections, tend to correlate with internal conflict and therefore state-inflicted control. 24 of the countries they were tracking had already imposed shutdowns in the past.

One of the countries flagged in 2024 was Venezuela, which imposed internet restrictions after Maduro’s 2024 presidential win. In the aftermath of Maduro’s recent capture, the state monitored messaging platforms and jailed journalists, just a few ways in which the internet was used as a tool to quell a mass uprising.

“Imagine that you have all these stories,” Amir said, “and you are alone in your home, in your room. You cannot communicate with anyone.” Not even your own mom, he added.

China’s internet system is its own galaxy, which it began establishing when the internet first hit the ground in the 1980s. Commonly known as ‘The Great Firewall,’ it is so centralized that China accidentally disconnected from the world for nearly an hour last August.

As opposed to China, Russia was once home to a very open internet.

Although Vladimir Putin shrunk access to media and information over the course of his reign, limits reached new heights during the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Everything started to disappear — not only due to government control, but also due to companies like Netflix, TikTok and Apple pulling back from operating in Russia.

In 2025, the Kremlin took an active stance against Western technology by introducing a state-approved super-app called MAX, which would be pre-installed by law on all new smartphones sold in Russia. This came after it started to limit voice and video calls on WhatsApp and Telegram.

Western countries are often considered immune to the threat of government-imposed internet disruptions, but they should not get too comfortable.

In the U.S., for example, certain laws give the president sweeping powers over communication networks. Under the Communications Act, the president can order the closure of radio stations and internet networks if he declares a national emergency or deems national security to be under threat. Thus far, though, these powers have not been exercised.

The reality is that many Western democracies do have some extent of power over internet systems, but have not yet leveraged it as a tool for suppression.

But as well-established democracies around the world are starting to wither, this could become a more global issue.

A self-contained internet ecosystem, where messaging and media are concentrated in a small number of platforms, makes large-scale disruption possible. In Iran, cutting access through just a few companies can render phones and computers largely unusable within minutes.

Internet disruption does not always come in the form of a government shutting off access at home. It can also be imposed from afar. Alongside software-based censorship and throttling, states are increasingly targeting the physical infrastructure that keeps the world online, from data centers to the undersea cables that carry the vast majority of global internet traffic.

Being cut off from the internet can be debilitating.

“Imagine you are waking up into darkness. Complete darkness,” explains Amir. “The only source of light you have is the light of a candle.”

That was how he described daily life during Iran’s earlier internet crackdowns, when access was limited but not yet entirely severed. In 2009, he wrote about moving through the city during the day, gathering information, sharing what he could anonymously, trying to document what was happening before night fell.

Now, he says, it is much worse in Iran.

“Imagine you are yelling for help and no one responds,” said Amir. “It’s only you.”

Amir worked as a software developer mainly focused on security, but his focus has always been on how people can use the internet for their own activism. Back then, circulating a petition meant sending around emails and asking for replies to an individual account, consolidating those signatures, and tracking responses.

Showing his peers the wonders of something as simple as Google Forms altered their capabilities for digital activism.

In February 2010, right after Iran’s 2009 presidential election, Amir left Iran and arrived in Italy where he was a political refugee. Now, he lives in Brooklyn, New York.

During that 2019 Iranian internet shutdown, the Access Now team offered Amir the opportunity to go to Berlin and raise awareness about the situation in Iran.

During a panel on that trip, Amir realized that there were seven Iranians recording his talk about internet shutdowns in Iran. In a presumably safe, democratic country, there he was, under threat once again.

“Even though I was in Berlin, I was really scared,” said Amir.

But this fear, this danger, this helplessness, is not just Amir’s story.

He made that incredibly clear.

“I appreciate that you like my story,” he told The Counteroffensive. He paused. Swallowed. “This is the story of my people.”

Featured subscriber note from reader Tai:

“Praying for you, Myroslava and Nastia, as well as the rest of the team. Folks who are able should keeping feeding the tip jar and find ways to donate to various organizations purchasing batteries for Ukrainians. Slava Ukraini.”

NEWS OF THE DAY:

By Oksana Stepura

Good morning to readers; Kyiv remains in Ukrainian hands.

ZELENSKYY PROPOSES UKRAINE TO PLAY CENTRAL ROLE IN EU ARMY: Zelenskyy has proposed that Ukraine’s army serve as the “backbone” of a future joint European military force to counter Russia’s growing army. Zelenskyy emphasised that “without the Ukrainian army — without a million Ukrainians — [the European army] won’t manage.”

Zelenskyy has reiterated calls for a European army of at least three million, as Russia aims for at least 3 million troops by 2030. European leaders have discussed the idea at the Munich Security Conference but have taken no concrete steps in implementing it.

RUSSIA LAUNCHES LARGEST AIR STRIKE OF 2026: Russia launched its largest aerial attack on Ukraine this year, firing nearly 400 drones and 21 missiles overnight, primarily targeting energy infrastructure and residential buildings.

This attack, which left over a million people without power in sub-zero temperatures, occurred hours after peace talks in Abu Dhabi. In an unprecedented move, Russia deployed Kh-22 missiles, which were originally designed to be used against aircraft carrier groups, their combat payload being 950 kilograms.

SANCTIONED RUSSIAN TANKER ADRIFT IN MEDITERRANEAN: A 19-year-old Russian shadow fleet tanker is currently adrift off the coast of Algeria after suffering a suspected mechanical failure, according to tracking data analyses by Bloomberg.

As the majority of Russian shadow fleet tankers, it’s over 15 years old, which increases the risk of malfunctions, collisions, and oil spills, posing a threat to the environment.

CAT OF CONFLICT:

Oksana’s Mary is kneading a blanket.

Stay safe out there,

Best,

Jacqueline