There’s an old saying that all roads lead to Rome. These days, for a young Cuban with limited options and a taste for risk, many of those roads lead to Tula, the hometown of Russia’s 106th Guards Airborne Division. There, recruits trade island heat for assault trooper life, and ruble-denominated contracts. They’re not alone: from Havana to Kathmandu to Accra, foreigners are enlisting in the Russian military, often with little understanding of the language - or the war they’re about to enter.

In 2023, a massive data leak facilitated by Ukrainian cyber activists exposed hundreds of Cuban mercenaries who had joined Russian forces. The revelations were first examined in detail by Inform Napalm, an open-source intelligence group from Ukraine. After obtaining access to the leak through the platform called “Dallas-Park”, which contains breached Russian emails and internal documents, we reviewed recruitment records, contracts, and personal data related to Cuban fighters and others. Using these materials, along with additional sources and open investigations, our team set out to answer a broader question: how many foreign nationals are serving in the Russian military and what do we know about them. The answers are not always precise, but the overall picture is beginning to emerge

Table of Contents

Intro

I. The Island Soldiers

i) Tracked and Mapped

II. Signed and Sealed

III. Recruits without Borders

I. The Island Soldiers

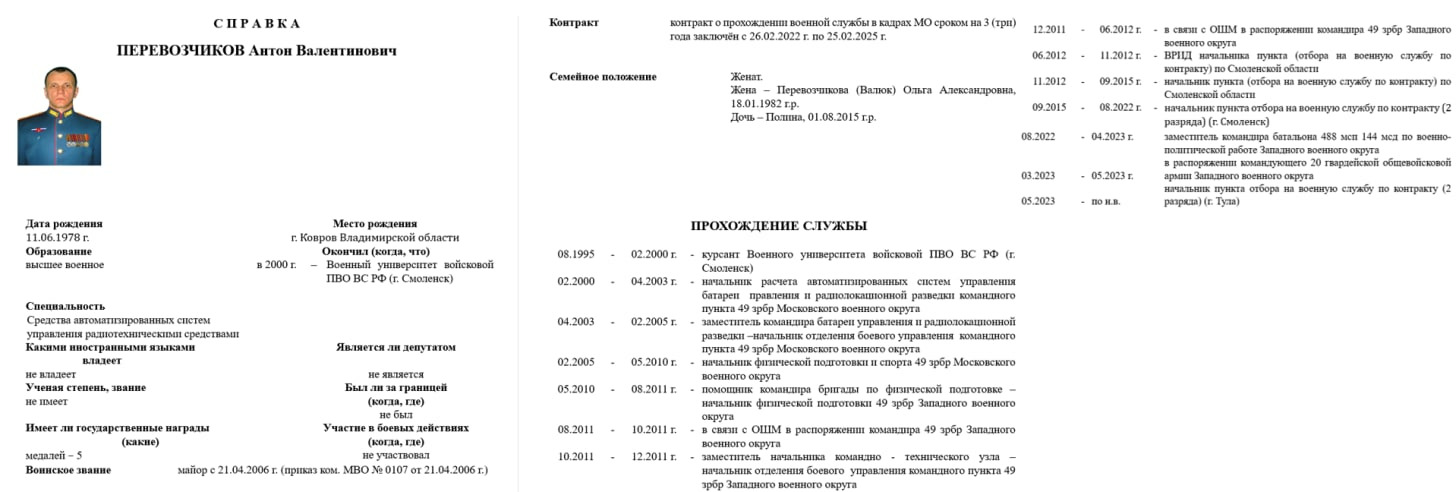

The story begins in 2023, not in warm and sunlit Cuba, but in the colder and less sunny Tula region, a few hundred kilometers south of Moscow. Inside a typical Soviet-era building, Major Anton Perevozchikov of the Russian Armed Forces, chief of the Contract Military Recruitment Office in Tula, was reviewing translated Cuban passports and studying the latest recruits hoping to serve in Russia’s military. While it is tempting to speculate about what drew these Cubans to a distant war, perhaps even inspiration from Tolstoy’s War and Peace, the contracts and addenda written in Spanish-language suggested a different story. The generous payments pointed at far more practical motives.

Unbeknown to the major, Ukrainian hacktivists had infiltrated his network and accessed sensitive materials, including passports, contracts, and personal information of the mercenaries. They quietly copied the data and correspondence. Using details from the leak, Frontelligence Insight was able to identify and track several of the mercenaries through their digital footprint, including activity on social media.

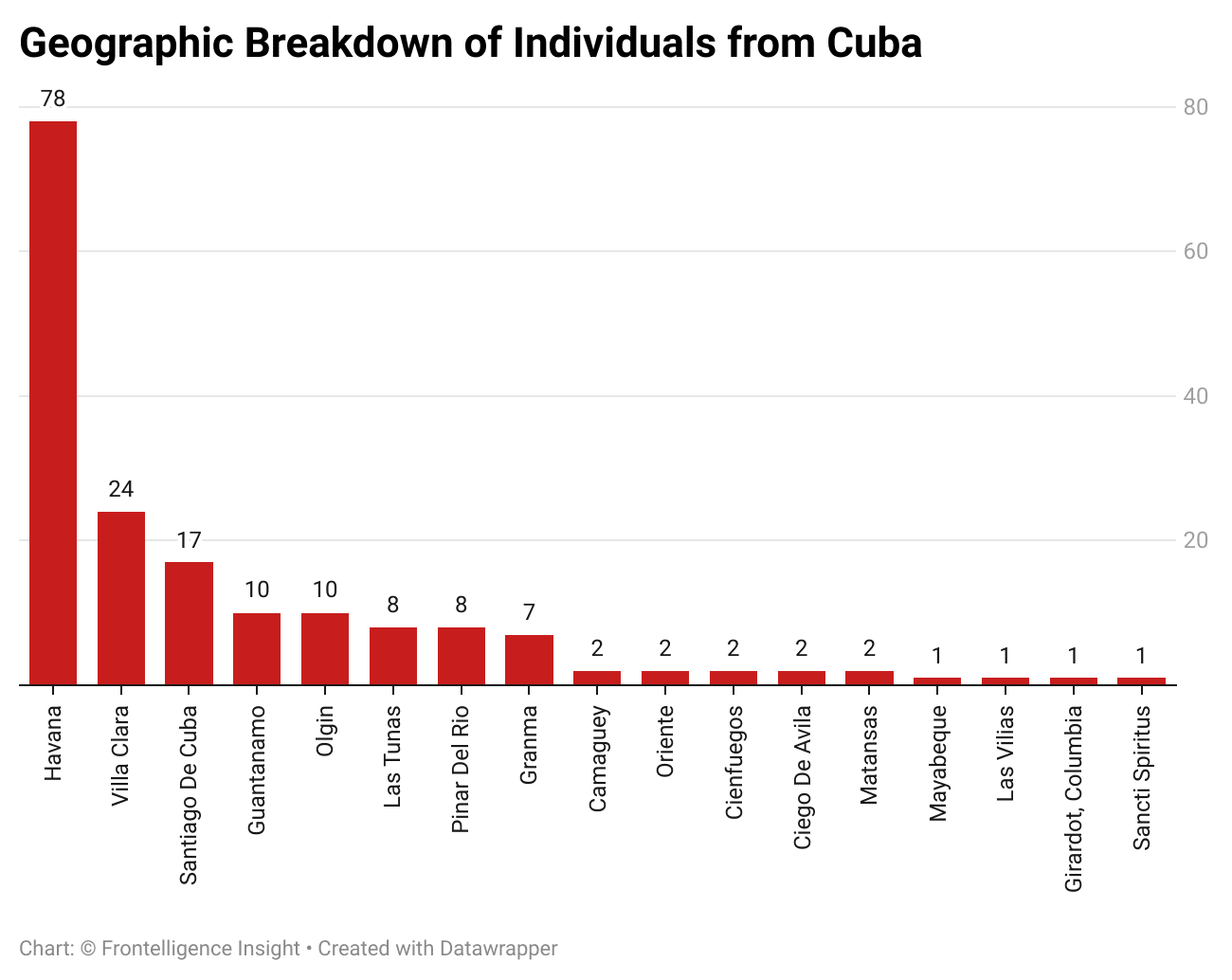

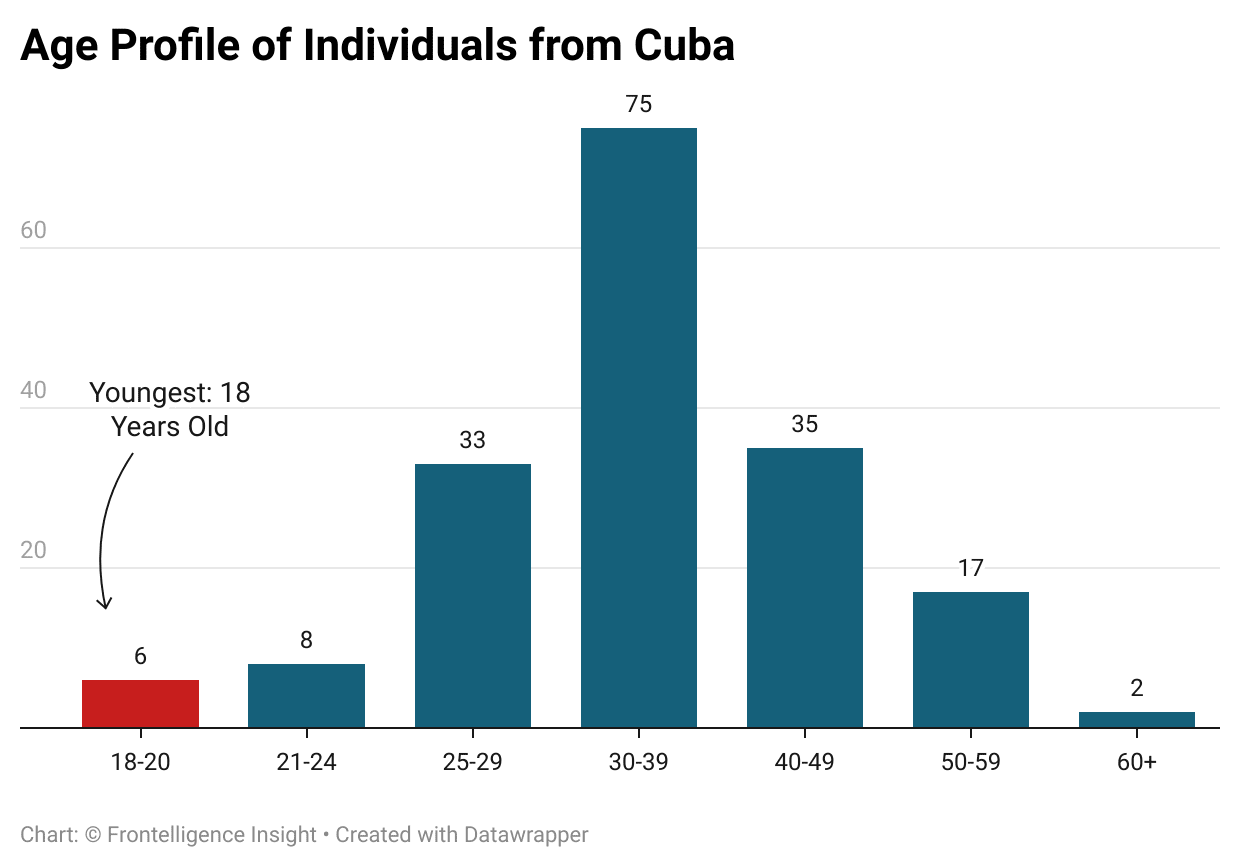

After manually reviewing over 199 Cuban mercenaries, we compiled a brief demographic profile. Our dataset analysis was based on 176 verified records. This group likely represents at least a third of all Cubans fighting alongside Russian forces, making it a highly representative sample.

As we expected, the largest share of Cuban mercenaries came from Havana, Cuba’s capital and most populous city. The largest age group was 30 to 39, followed by those aged 40 to 49. This was somewhat unexpected, as our team had anticipated a younger overall profile among the recruits.

The youngest recruit was 18 years old, while the oldest was over 60. We cannot confirm whether the oldest individual passed all required examinations, and we were unable to track him in Russia. However, we did identify several recruits over the age of 40 who were taken into the Russian armed forces.

This was not the last group of Cubans to arrive in Russia, and recruitment operations were likely coordinated with the Cuban government. Orlando Gutierrez-Boronat, co-founder of the U.S.-based Cuban Democratic Directorate, an NGO that advocates for democratic change in communist Cuba, told Ukrainian investigators from Schemes: “We can estimate that around 5,000 Cuban soldiers are fighting for Russia. This network could not function without the Cuban regime’s approval.”

While our team concurs with that assessment of the regime’s involvement, we remain somewhat skeptical about the estimated number of Cuban fighters. More on that shortly.

i) Tracked and Mapped

With their full names in hand, it was not difficult to trace their locations and identify their digital footprints on Russian social media platforms.

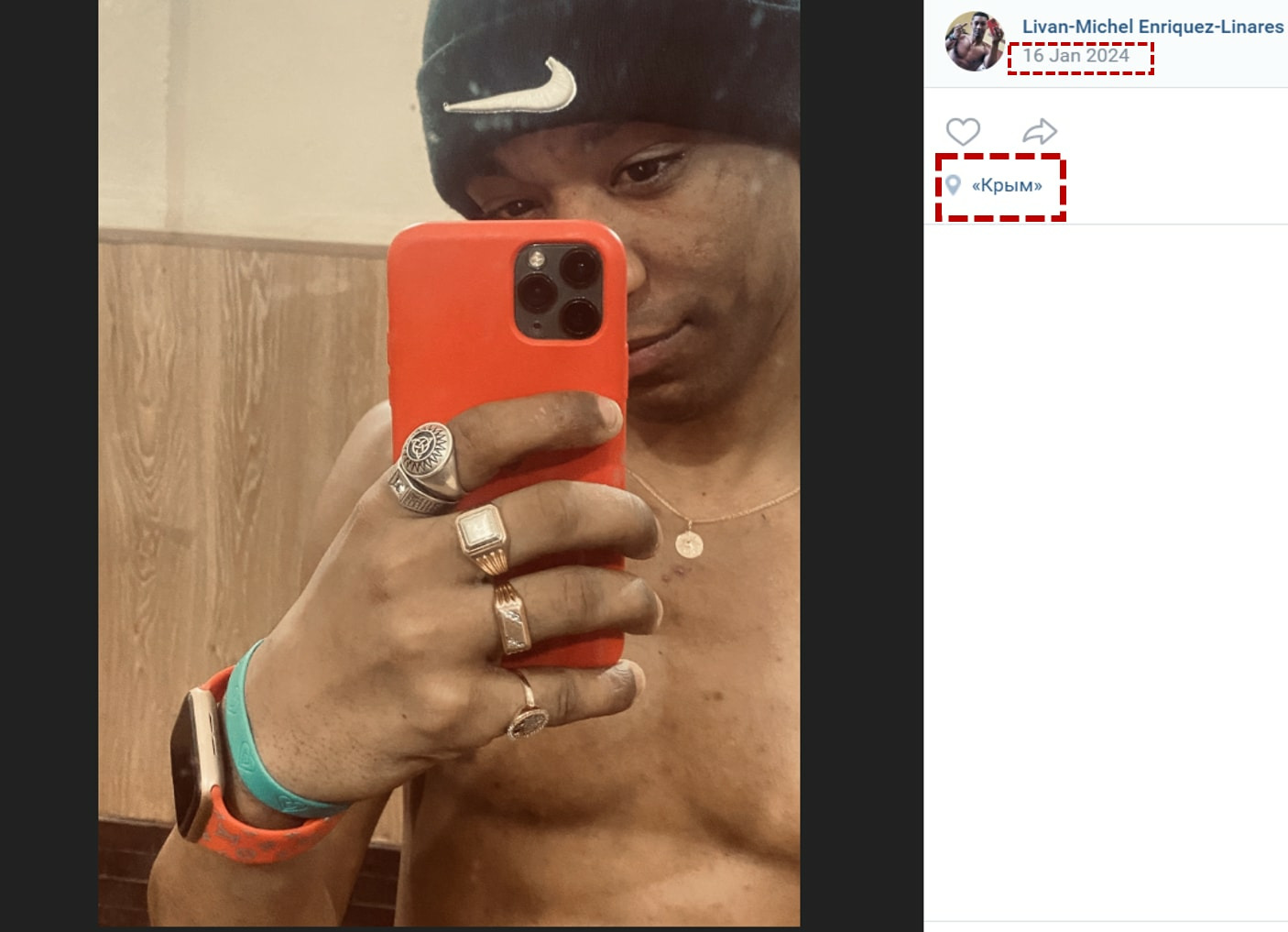

One individual, Enriquez Linares Livan Michel, born in 1999, proved particularly helpful. His social media profile included not only photographs but also geolocation data, which revealed his whereabouts.

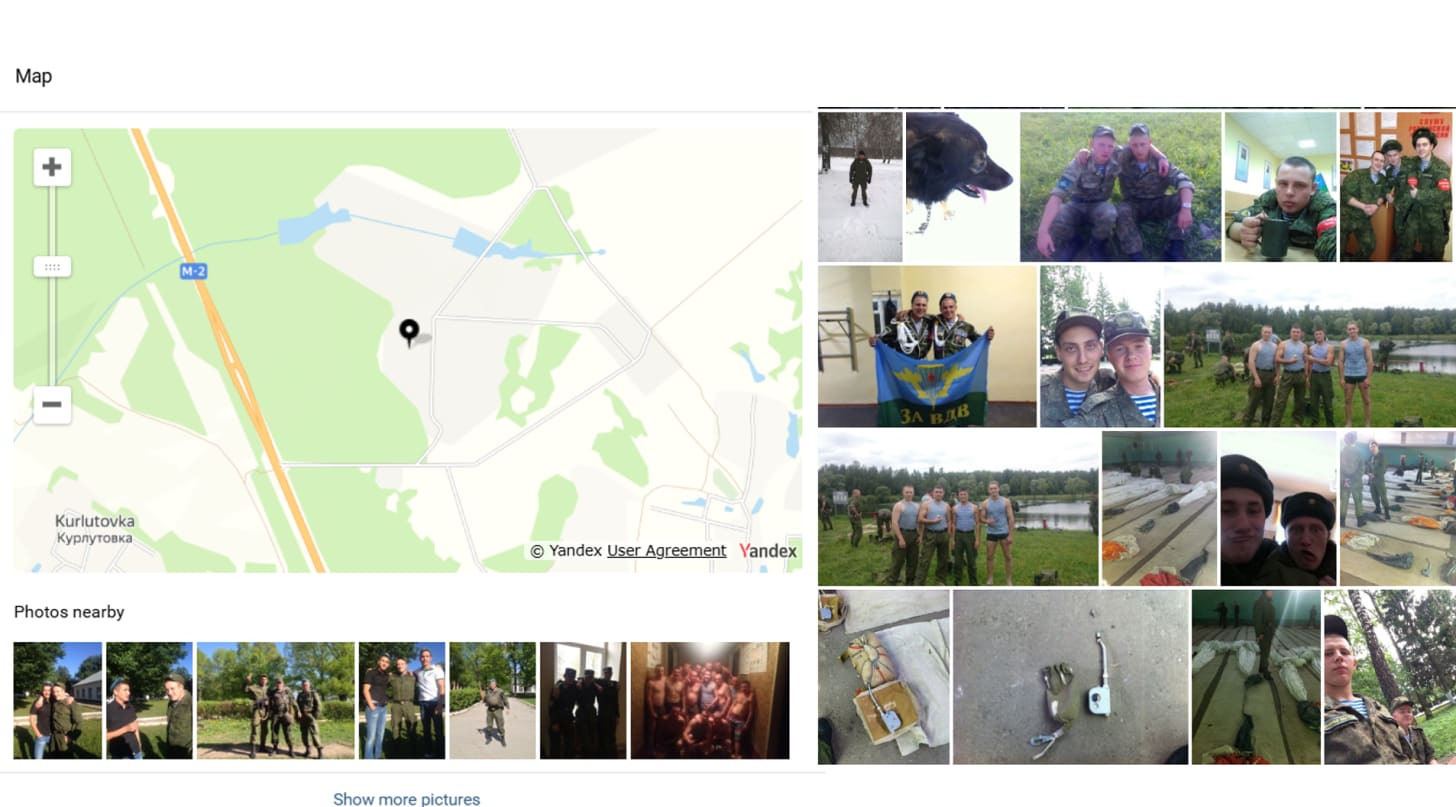

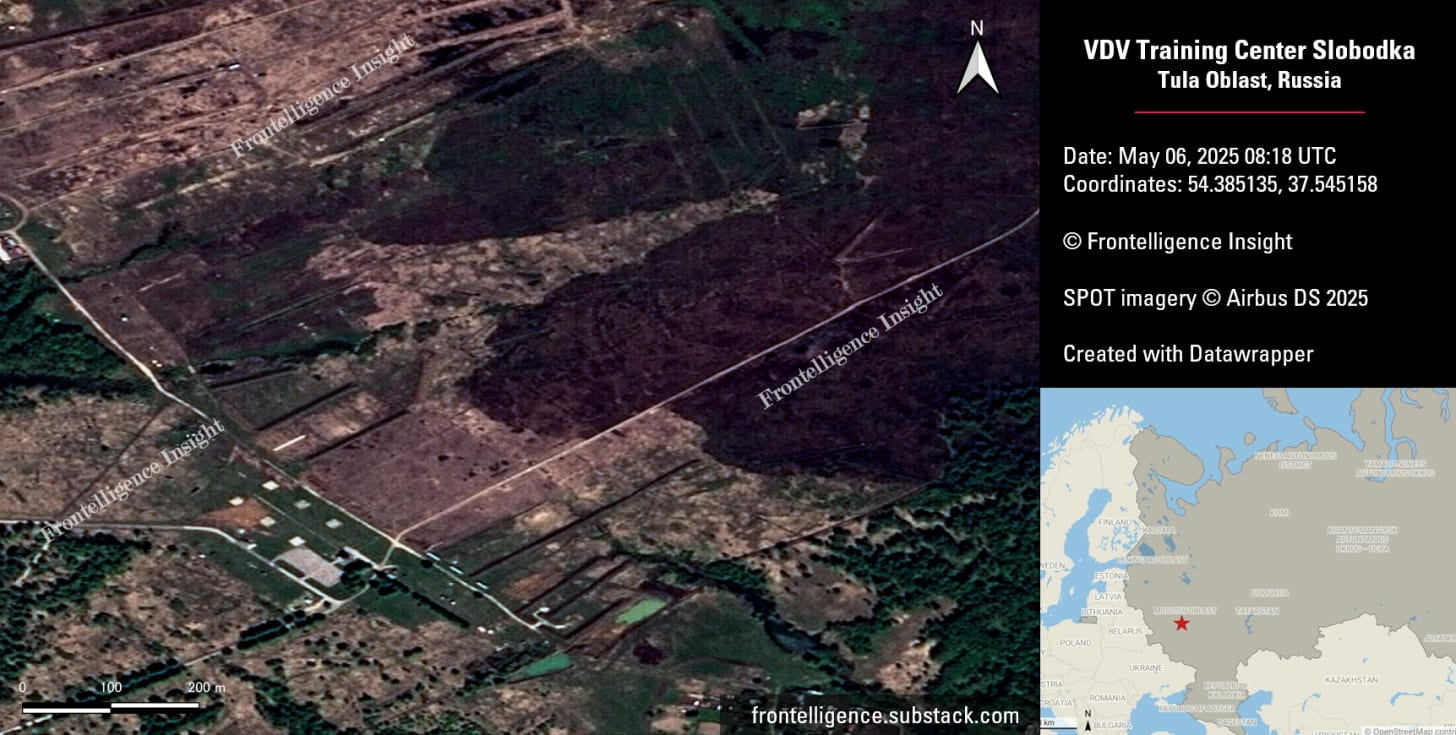

Although the location on his photo was labeled “Krym”, the Russian word for Crimea, it was not in Crimea at all, but near Tula - the same city where recruitment was taking place. When clicked, the VK platform redirects to Yandex Maps, showing not only the specific location but also other uploaded photos from the surrounding area. The frequent appearance of Russian paratroopers in distinctive striped shirts and blue berets, along with parachutes visible in images spanning from the early 2010s to the present, suggests that the facility remains actively used by Russian airborne forces.

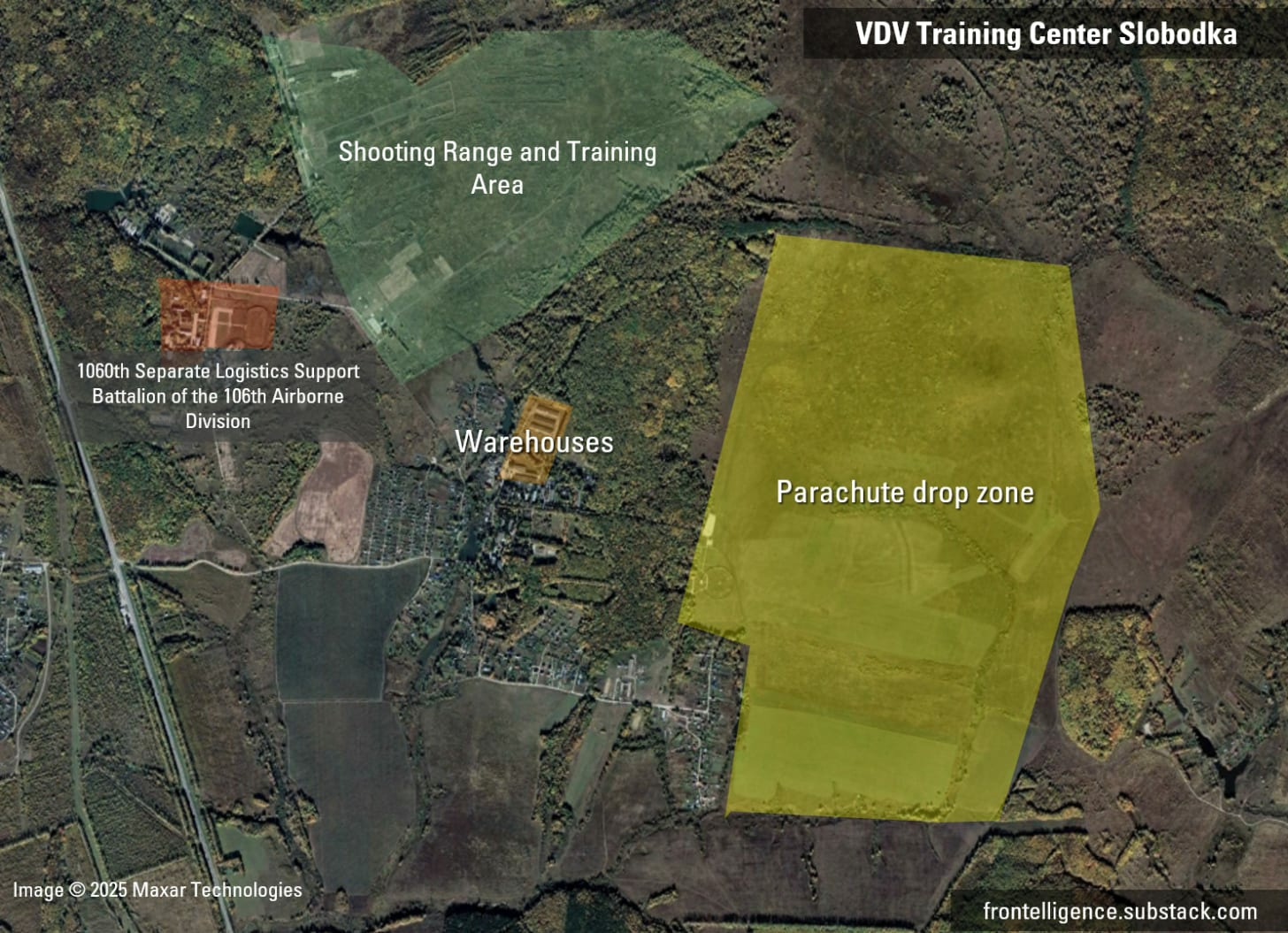

This location was not unfamiliar to our team. It is a training area used by the 106th Guards Airborne Division, near a parachute landing zone known as Slobodka, which is famous for hosting the first manned airborne vehicle landing tests in the Soviet Union.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

To verify our findings, we tracked another identified Cuban recruit who posted photos on VK under the name Luis Darien and geolocated him directly within the training grounds, specifically on territory officially used by the 1060th Separate Logistics Support Battalion of the 106th Airborne Division. These findings corroborate information published earlier this year by Schemes (We recommend reading their investigations for more details).

As of June 2025, the Slobodka training grounds remain actively in use. Although we cannot definitively determine whether they are used exclusively by Russian forces or also by Cuban recruits, imagery posted by Cubans themselves confirms they underwent training there at least in 2024.

As seen on the medium-resolution satellite imagery, dated May 2025, both the shooting range and the vehicle training area, typically used by BMDs here, show visible vehicle tracks and signs of grass fires, a typical pattern observed during live-fire training exercises.

Across the road from the main base, a tent camp is clearly visible - likely set up for recruits of the 106th Airborne Division.

Cubans, however, are not the only foreign recruits to have trained there. In 2023 and 2024, we also documented isolated cases of Serbian nationals being processed through Tula and the facilities of the 106th Airborne Division. Some of them ended up serving in 119th airborne regiment of the 106th division.

II. Signed and Sealed

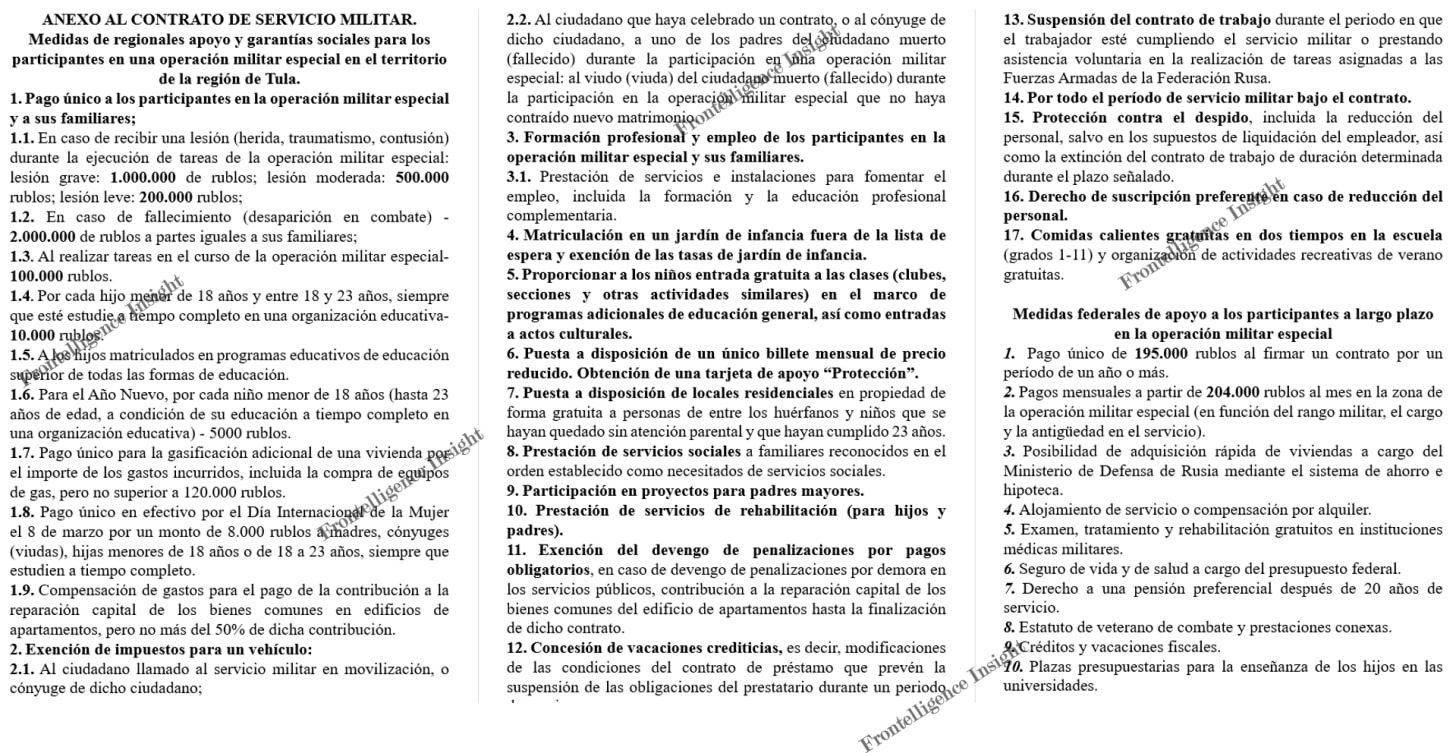

According to the contract in Spanish, which matches standard agreements issued in 2023, the mercenaries from Cuba were offered the following terms:

A one-time signing bonus of 195,000 rubles (approximately $2,500 as of July 2025) for agreeing to serve for one year or more.

Monthly pay starting at 204,000 rubles (roughly $2,600 as of July 2025) while deployed in the so-called "special military operation zone."

Compensation for injuries sustained during deployment included:

1,000,000 rubles for severe injuries

500,000 rubles for moderate injuries

200,000 rubles for minor injuries

In the event of death or being declared missing in action, the contract promised a payout of 2,000,000 rubles, to be divided equally among the recruit’s family members.

By the standards of many developing countries, these are very lucrative salaries. It’s also worth noting that the contracts explicitly mention service in the special military operation zone, along with provisions for injury and death compensation. This indicates that while Russian recruiters may deceive some foreigners by downplaying or misrepresenting their potential involvement in combat, they do not completely omit references to the special military operation.

Depending on the case, individuals arrive in Russia through different channels. Some purchase tickets independently and travel on their own to Moscow, while others receive direct logistical support from the Russian side. In such cases, their arrival is organized in groups under the guise of construction workers or similar labor-related projects. In a few anecdotal instances, we documented direct government-level cooperation, where mercenaries were transported on regular commercial flights without any additional cover.

There are also numerous reported accounts of Russia using deceptive tactics, such as inviting foreigners for non-military jobs and then pressuring them to join the armed forces. These efforts often exploit the recruits’ limited knowledge of the Russian language and legal system. However, we have not been able to independently verify these claims.

III. Recruits Without Borders

Even as our team cautiously estimates that slightly more than 500 Cubans and a similar number of Serbs have either travelled to Russia or attempted to enlist, determining exact figures for each nationality remains difficult. That being said, based on two primary data points, we are able to offer a realistic range.

One key reference comes from an investigation by iStories, a Russian investigative outlet known for its credible and high-quality reporting. In April 2025, using data from a hacked Unified Medical Information and Analytical System (EMIAS) database, iStories analyzed the number of foreigners processed through the Moscow recruitment center for contract military service, including a breakdown by nationality. We regard this as a reliable source, which we will discuss further below.

A second source consists of internal personnel documents from several Russian brigades and divisions, including lists of foreign fighters. While these records provide only a partial picture, since we do not know how many foreign recruits are assigned to each unit across Russia or how evenly they are distributed, they help us approximate the overall scale.

Thanks to the iStories investigation, we know that at least 603 Nepalese citizens visited the recruitment center in Moscow. The first Nepalese appeared in the Russian military no later than May 2023. After this becoming public in 2023, Nepalese government has taken steps to curb the flow of its citizens enlisting in Russia, but iStories notes that four Nepalese recruits still passed the selection process for contract service in January and February 2024. Yet, this number is significantly lower than in 2023, and the trend to its decrease likely has remained in 2024 and 2025.

iStories also reported that eight Cuban and eight Serbian citizens visited the Moscow recruitment center over the course of the year. While this figure is much lower than our estimates and the number of confirmed cases, it is likely explained by the fact that many Cubans were processed through the recruitment center in Tula rather than in Moscow.

Estimating the number of recruits from Sub-Saharan African countries is more difficult. The sources of these recruits vary significantly. Some arrived in Russia on temporary visas or as students and later chose to enlist. Others requested Wagner Group or the African Corps assist them while still in their home countries. In some cases, individuals were lured with misleading job offers unrelated to military service. While we were unable to fully systematize this data, we assess that the total number of Sub-Saharan African mercenaries remains relatively small and is unlikely to exceed a battalion.

Upon reviewing Russian military documents related to enlisted soldiers in various brigades and regiments, we found relatively few foreign personnel - sometimes fewer than a single platoon, and in other cases around two platoons. This suggests that the overall number of foreign fighters is likely much smaller than some media reports imply. For instance, if there were truly 5,000 Cubans or 15,000 Nepalese involved, as reported by CNN, we would expect to see a much more substantial presence across these units - not just a few sections or platoons of mercenary soldiers in total. Another indicator is the number of prisoner-of-war (POW) videos. When comparing interviews with captured soldiers, foreigners represent a tiny fraction -disproportionately smaller than the number of regular Russian citizens.

Based on this, our team estimates the total number of foreign mercenaries to be between 4,660 and 8,000. Taking into account desertions, casualties, and injuries, the actual number of foreign fighters consistently present on the front lines is likely even lower. The figure may appear significantly lower than media reports from the past few years suggest. Yet, after examining the total number of brigades and regiments, multiplying by the average number of foreign fighters per unit, factoring in higher concentrations within airborne divisions, and subtracting those who have ended their contracts or been killed since 2023, we believe our estimate offers a more realistic and accurate range.